This is a set of pictures taken at our farm in the New England highlands of Guyra Shire over the last couple of years. These images evolved naturally out of simply carrying inexpensive compact digital cameras around with me while completing everyday tasks or walking in the bush.

Sheep at Dusk

Wes Hicks, Sheep at Dusk

Blue sheep

Wes Hicks, Blue Sheep

Frost

Wes Hicks, Frost

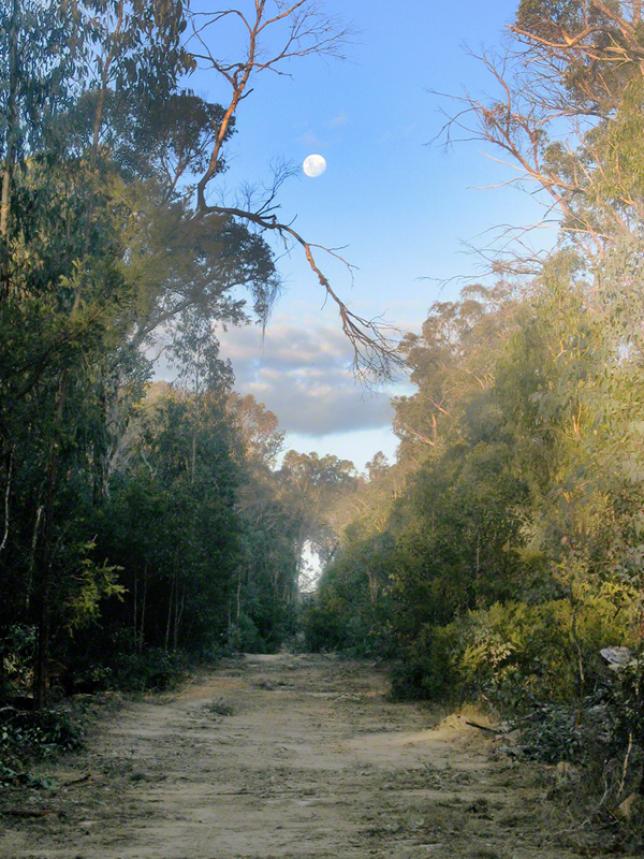

Firetrail Moon

Wes Hicks, Firetrail Moon

Dog and Horse

Wes Hicks, Dog and Horse

Pond Roo

Wes Hicks, Pond Roo

Big Stringy

Wes Hicks, Big Stringy

Cairn

Wes Hicks, Cairn

Decades ago, as a young art student studying photography with George Krause at the University of Houston in Texas, I was steeped in a gestalt of dynamic urban street photography that emphasised the capture of ‘little moments’, which implies something more than can be contained within the rectangular confines of a still image. In that tradition, a photographic still encapsulates a narrative or an enigma, but also functions as a kind of visual history making.

After art school, I practiced painting and sculpture grounded in styles informed by non-representational modernism. As a result, I am always alert to the tension between a photograph’s formal, abstract qualities and its content. It is the struggle, and resolution, between a photograph’s narrative and the utterly visual language in which it is expressed, which makes a photograph interesting to me.

More naturally than the other plastic arts, photography instantly lends itself to representing the exterior, physical world. But no matter how explicit a photograph is, it must also be complicit with the viewer in order to form a relationship larger than the sum of the image’s parts. It is the ineffable entanglement between the image – which after all is nothing more than so many pixels on a plane – and the mind’s eye, where the magic takes place.

Recently, the revolution of digital photography has opened up the floodgates of possibilities and, paradoxically, this limited the authority of photography. As technology melds mediums, art is becoming Herman Hesse’s Glass Bead Game, wherein anything is possible but nothing under the sun is new. I find this bewilderingly new infinity of possibilities a bit like lying on your back on a clear evening, looking up at the Milky Way, and thinking about the all the unimagined worlds that lie out there. There is very little to be done about it, except wonder blankly in awe.

Of course, in digital photography you can explore at least a finite subset of the infinity of possibilities, but after a few years, even the most diehard digital triumphalist will discover that the only possibility that remains a scarce resource is authenticity.

Meanwhile, back at the farm, I take pictures and process them using Photoshop, sometimes tweaking an image for hours or days only to delete the results and start over again. I do not use this technology for its special effects, but instead to ameliorate the camera’s distortions to find what my eye really saw that was numinous in the moment. Ironically, with all the power of digital sorcery at my fingertips, the greatest satisfaction lies in those rare few photographs that require only the lightest touch in the desktop darkroom.