Technology has transformed photography. For many, the photograph is now the proof, not the record, of lived experience. The contemporary culture is suffused with digital images. They spread like viruses, we play host to them with every digital post we make. There would seem to be little use for damage in this process. Yet there is. Many mobile phone images are instantly processed with filters that emulate damage. Overexposure, vignetting, and light leaks have become part of the language of social photography, applied without thought or any understanding of the real damage they emulate. I think that the success of tools such as Instagram is a sign that our culture is feeling the loss the tangible moment, the existential temporality that photography so eloquently speaks, the damage that my images concentrate.

Number 1

My first real camera was a Zenit 12XP. It was a beautifully clunky soviet camera with good optics, and controls that were practically anti-ergonomic. My second real camera was a futuristic swivelling Nikon Coolpix that needed new batteries every eight shots. I was hooked. Digital photography increased my options exponentially. Everything could be altered. Damage could be avoided. Any focal length, any film speed, any choice could be made and then unmade. This was liberating for my younger self. With time, the infinitude of the digital process grew stale. The pixels lost their gloss. I picked up a cheap plastic medium format camera that was the antithesis of the digital camera, and set about recovering what had been lost from my photography.

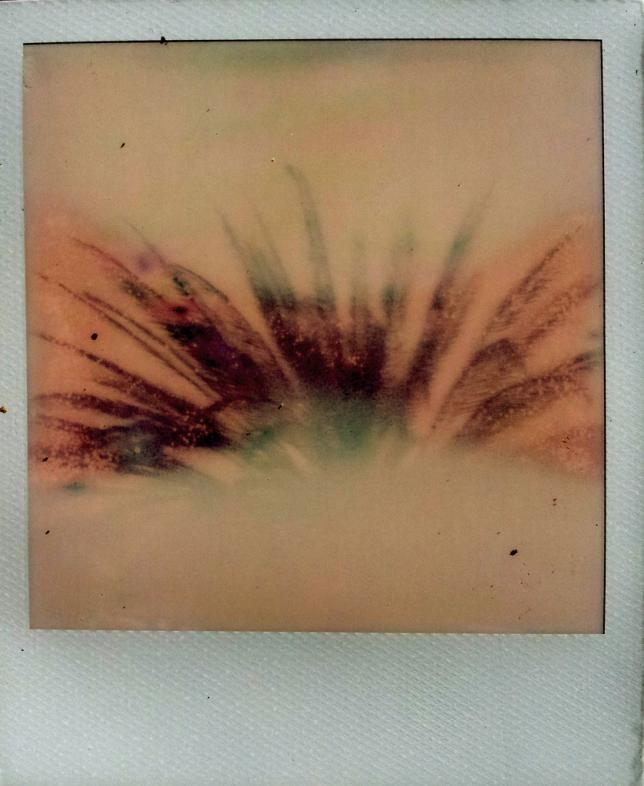

The series of images that comprise the Damage series are largely from that plastic Holga camera. In reality they are hybrid images, finished in Photoshop. Care has been taken to take little care throughout the processes from which these images were created. Light leaks abound, backs fall of cameras. Fingerprints smear. Dust adheres. Much damage is done by the time the film reaches the scanner. Digital image processing is a necessity with most images taken on a Holga or similar camera, as the prints tend to be over or underdeveloped, and contrast is minimal. The washed out images and the damage they have accrued become the source material for a second round of creative processing—selection, sampling, emphasising. This second phase is, as much as possible, carried out as quickly as possible, a process somewhat akin to the Surrealist practice of automatic writing, a process that goes with the grain of the damage inherent in the source image.

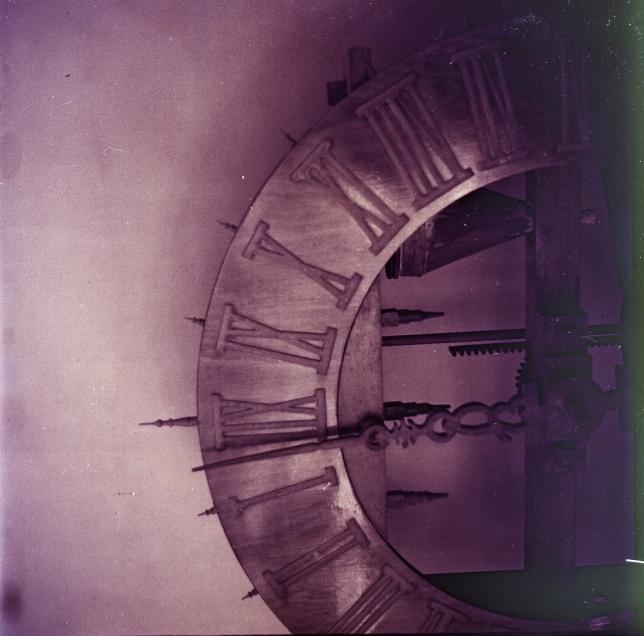

Barthes (1981) writes of the poignancy of the photograph, and much of his logic hangs on the physicality of the analogue film process. The photograph, or at least the photographic negative, is a tangible relic of a temporal and physical moment; a moment that will remain unreachable from the instant the shutter button is pressed. A collection of photographs can therefore be interpreted, or more properly be felt, in two different modes. On the one hand, a photograph is a reminder of past times and past places, a memento, an extension of memory. On the other hand a photograph is a kind of scar; a little piece of experience, albeit one of an infinite number, that has been somehow extracted from us and placed behind glass.

Technology has transformed photography. For many, the photograph is now the proof, not the record, of lived experience. The contemporary culture is suffused with digital images. They spread like viruses, we play host to them with every digital post we make. There would seem to be little use for damage in this process. Yet there is. Many mobile phone images are instantly processed with filters that emulate damage. Overexposure, vignetting, and light leaks have become part of the language of social photography, applied without thought or any understanding of the real damage they emulate. I think that the success of tools such as Instagram is a sign that our culture is feeling the loss the tangible moment, the existential temporality that photography so eloquently speaks, the damage that my images concentrate.

Barthes, Roland 1981 Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux