This piece is a personal musing on the song lyric as a poetic departure from poetry and how a personal journey to Ireland over forty years ago came back as a lyrical future of nostalgia (to paraphrase Milan Kundera). It addresses how the song lyric can look at history, biography and wishful thinking in a linear narrative.

Keywords: lyrics; poetry – poetics – art – history – Kundera – nostalgic future

I can’t write poetry. Or perhaps that should be, I don’t write poetry.

The truth is I never really try—not in the conventional reading of the word, poetry. Yet, I read a lot of poetry; as a form of artistic representation I find it hugely satisfying—and the arguments behind it as an artistic form are firmly embedded in my own idea of art. Art marks us out as homo fabula, the storytelling species, no matter the manner of its representation and engagement, whether it be poetry, prose, painting, dance, sculpture, photography, or even bubble making. I took this picture of an anonymous bubble maker in Central Park, New York, February 2013:

I am constantly impressed by the ephemeral nature and simplicity of the light sculpture he produced. Each bubble was a performance and each differed from the previous bubble and the next, catching different light and producing different tones and hues, depending on parallax, the time of day, the moment of lens and shutter capture.

The bubble I photographed was accompanied by a saxophonist, elsewhere in the park, playing a version of Dave Brubeck’s Take Five. Of course, any child could do that, blow a bubble over another’s soundtrack, but what was that moment if not sheer poetry; a version of Kant's notion of beauty and the sublime. It was also an example of the moment Walter Benjamin referred to as a Dialektik im Stillstand—dialectics at a standstill. Benjamin writes in the Arcades Project that art ‘prefigures’ the arresting of thought and action, historical time becomes encapsulated so that the crystalised effect of this dialectics at a standstill is to render time as present, rather than as a flow of past/present/future, in the imagistic configuration of the now—in the immediacy of the actual event as the bubble unfolds and then pops. In other words, the immediate output of the performance moment throws:

‘a pointed light’ on what has been. Welcomed into a present moment that seems to be waiting just for it—‘actualized’, as Benjamin likes to say—the moment from the past comes alive as never before. In this way, the ‘now’ is itself experienced as preformed in the ‘then’, as its distillation. (Translators’ Foreword to The arcades project 1999: xii)

An image lingers, then reforms as a snapshot of a memory. My photograph, as a representation of the event, does little justice to the event itself and only really invokes part of my memory of it. To some extent, the poetry of the situation could be captured and enhanced through further representation—in an accompanying poem, or a painting, or as a textual intervention which would open up a dialogue.

I am reminded here of W.H. Auden’s poem, ‘Musée des Beaux Arts’, which is a textual intervention directed at Breughel’s Landscape with the fall of Icarus—which is itself a textual intervention referencing Ovid’s poetic telling of the Icarus story. It cannot be said Auden’s ekphrastic poem improves Breughel’s Landscape with the fall of Icarus but it engages with the famous painting as another artistic form that helps to capture the ‘pointed light’ moment. So, too, does William Carlos Williams’ poem with the same title:

According to Brueghel

When Icarus fell

It was spring

…

unsignificantly

off the coast

there was

A splash quite unnoticed

this was

Icarus drowning

As the poem re-draws our attention to the painting, both painting and poem remind us of the story of Icarus as a trope. Icarus appears in various guises in literary and visual art over many centuries, following his early appearances in works by Ovid, Virgil, Apollodorus, Pausanias and Diodorus, and his story continues to illuminate something about contemporary life and what Auden called the ‘human position’. Is this not the ongoing discourse we call art; or what Benjamin might have called the ‘pointing light’ of art—a powerful example of its protean innovative creative and critical reflections and engagements?

Alexander Pope in An Essay on Criticism (1711) wrote that

True Ease in Writing comes from Art, not Chance,

As those move easiest who have learn'd to dance,

'Tis not enough no Harshness gives Offence,

The Sound must seem an Eccho to the Sense.

Although many contemporary poets may resist Pope’s prescription for a mellifluous poetry, as far as poetry as a textual intervention is concerned, the new so often comes from the old and, as it does so, the contemporary life we know is reflected and illuminated in both a pointed and pointing light. In his essay, ‘Against György Lukács’, Bertold Brecht insists:

Our concept of realism must be wide and political, sovereign over all conventions ... Reality changes; in order to represent it, modes of representation must also change. Nothing comes from nothing; the new comes from the old, but that is why it is new. (1977: 82)

But I can’t write poetry. The truth is, I never really try to write poetry.

Of course, like Peter Cooley (2012) I have the odd travelling monostich floating through the notebooks I have carried throughout my life. I wrote one just the other day:

A red Ford Cortina isn’t a Mercury Two

And another:

Maria said, ‘Jesus, you’re cross …’

They were both written independently of each other and, isolated like this, their contexts are not clear.

But I don’t write poetry.

What happens for me is that I end up roping the lines into a melody and singing them along with a bunch of chords I have been strumming. Indeed, in this case, the tune came first as I strummed a G/Bm7/C and G on a mandolin. However, since I no longer play music live, these become little more than sensory doodles, bubbles blowing over a garden fence; a kitchen performance for sleeping cats.

Then I got thinking about the process of songwriting and what it actually meant to me because I would wither without it. In an email exchange with a friend she suggested I try to rationalise the creative process, or how it is for me at least. I have seen poets do this all the time. I found Katharine Coles a particular inspiration when I chaired a talk about poetry and creativity she gave in London; and Jen Webb was a further inspiration when I chaired a talk on a similar topic in Winchester. But how to approach it was the question. I mean, ‘A red Ford Cortina is not a Mercury Two,’ isn’t really Rilke’s opening line from his Duino Elegies (1912) about the angelic orders—Lines which Antonia Pont wrote so wonderfully about, saying, ‘the poem’s narrator wonders whether a person could withstand the embrace of an angel, and concludes that this is unlikely’ (2011). When I wrote about a Mercury Two I wasn’t thinking about hugging an angel, I was thinking about my younger self, leather upholstery on car bench seats and a movie called The last picture show (Bogdanovich: 1971).

With my friend’s suggestion came the inner voice that said, perhaps I am just ducking the relevancy, potency, potential (who knows the word) of the song lyric form that I ‘play’ with. For example, take the line I quoted previously, ‘Maria said, “Jesus, you’re cross …”’. The literal meaning is clear: Maria (Mary) is saying, ‘Jesus you are cross’; but when you sing this line it has an ambiguity. Try it—Maria says, Jesus your cross …’ The spoken/sung wordplay on Mary referring to Jesus’ cross, and Jesus being cross, introduces a playfulness that works the song into something different from the words on the written page. It is a different process, no less deliberate for the effect and ambiguity of meaning intended. Written down it doesn’t have the same resonance of delivery.

Thus, we begin to venture into the definitions that separate the song from the poem, where their parallel lines reveal them as siblings but not in fact the same. Pope says, ‘writing comes from art …’, but he would have to go down a long road to separate the poets from the balladeers, the poets from the librettists, the poets from the lyricists; and yet it doesn’t take us long to realise that the lasting word in these dichotomies is the word poet. Indeed even to say, ‘definitions that separate the song from the poem, where their parallel lines reveal them as siblings but not in fact the same’ leads us into murky waters.

Lyric poems and song lyrics share much in common, that is clear, and the main distinction between the two is a place to begin. Songs consist of lyrics which straddle the music that delivers them; poems essentially carry their music internally; in their rhythm and the rhyme, for example. To some extent, the difference is in the application, not the form, rhyme or rhythm. A poem can essentially be read and or spoken at any tempo, with any variety of pauses or breaks, although the punctuation is designed to have an influence on this. But the song tends to fit the metre and tempo of the music that has been designed to carry it. Even when an original song has been re-interpreted, the reinterpretation usually comes from an adjustment to the tune. Indeed, words that would be highly apposite for a spoken poem simply may not flow correctly when set to music. Nor indeed will every spoken poem lend itself to the lyrical form required of the song.

There is a difference in the act of delivery too. One is intended to be sung and received as a song; the other to be read silently or aloud. Because the performance of each is different so, too, are the associated writing processes. Essentially, a simple difference between song lyrics and poetry is the difference between two different art forms, in which sibling words can perform in different ways.

Edward Hirsch (2006) recalls,

I remember once walking through a museum in Athens and coming across a tall-stemmed cup from ancient Greece that has Sappho saying, ‘Mere air, these words, but delicious to hear’. The phrase inscribed into the cup, translated onto a museum label, stopped me cold. I paused for a long time to drink in the strange truth that all the sublimity of poetry comes down in the end to mere air and nothing more, to the sound of these words and no others, which are nonetheless delicious and enchanting to hear. Sappho’s lines (or the lines attributed to her) also have a lapidary quality. The phrase has an elegance suitable for writing, for inscription on a cup or in stone. Writing fixes the evanescence of sound. It holds it against death.

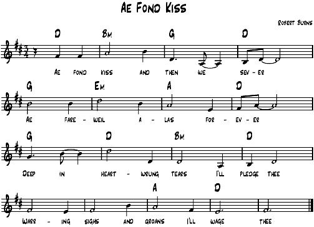

And surely Pope’s ‘eccho to the sense’ is also an echo of the Sapphic ‘Mere air, these words, but delicious to hear.’ The song lyric, like so much early poetry, is accompanied by a musical score to supplement the ‘mere air’. This ‘mere air’ becomes wrapped in a musical score that can be tabbed as notes on paper to accompany words—like the following lyric by Robert Burns (with thanks to Dick Gaughin for the transcription):

The word lyric derives from the Latin lyricus via the Greek λυρικός (lyrikós), the adjectival form of lyre, a musical instrument. The Greeks spoke of lyrics as ta mele, ‘poems to be sung’. It was not until the Renaissance that English writers regularly began to write their lyrics for readers rather than composing them for musical performance. The musical lyric form of a Dowland or Bird co-existed with the dramatic and poetical forms of Shakespeare, Sydney, Spenser et al. at a time when the full implications of Caxton’s 15th-century introduction of the printing press to England were beginning to be realised. There was a sense of inevitability that the written and sung words would develop hand in hand but differently.

The world changed, the means of delivery changed, the visual medium changed, the written medium changed, and with the coming of the printing press, oral traditions waned. Some words were beginning to be delivered as poems and others as songs — although I guess we have all seen those song lyric books made up to look like poetry collections, from perfomers Phil Lynott, Shane McGowan, Jim Morrison and Nick Cave.

In the light of these reflections, I would like to return to a consideration of my engagement with a particular song of mine that started as a monostich over 40 years ago and which I have only just finished. Something that Milan Kundera wrote resonates with what I am trying to say in the song, and relates to a story which may or may not be biographical but is relevant to the song’s context. Kundera’s ideas have prompted me to consider how I might write a whole series of songs as a reflection upon what was and what might or could have been.

‘The narrative future of nostalgia’ is a phrase Kundera (2009: 106-107) coined in an essay entitled ‘The Untouchable Solitude of a Foreigner (Oscar Milosz)’ and, for my process of writing and reflection, both the phrase and the title of the essay are relevant. Kundera writes of Oscar Milosz’s November Symphony, ‘I was entranced not by a myth but by a beauty acting on its own, alone, naked, with no outside support’ (2010: 106), and that the reason for his reaction:

lay in the discovery of something I had never encountered anywhere else: I discovered the archetype of a form of nostalgia that is expressed, grammatically, not by the past but by the future: the grammatical future of nostalgia. The grammatical form that projects a lamented past into a distant future, that transforms the melancholy evocation of a thing that no longer exists into the heartbreaking sorrow of a promise that can never be realized.

You will be all in pale violet, beautiful; grief

And the flowers on your hat will be sad and small. (2009: 107)

I was reading this at a time when I wondered what a songwriter should or could write about after nearly 50 years of such writing. Love songs seemed a little gauche at my age; and reflections on the past, loss, heartbreak and the like were a little too morose. Besides I had done them, seen them recorded; they sit within albums now. And, in any case, I didn’t feel morose, remorseful or reflective about a past of lost loves, life, chance and the like.

But the Kundera idea got me thinking about objectivity and I will return to it later because, first off, there is the other side of song writing, the re-interpretations. A song is not like a poem written primarily for the page. Songs can be significantly changed, even in terms of their meanings, when sung differently from the initial rendition. Introducing the ambiguity of a spoken performance of ‘Maria said, Jesus your cross’ is one thing but a sung performance that genuinely reinterprets a work—especially by someone who is not the writer—can make a huge difference to its reception. I had a ‘rake’s progress’ song, which I called ‘Don Juan’s Blues’, re-covered on an album as a love duet called ‘Hold Me’. It had moderate success and subsequently, I am told, this love duet version has been played at weddings and special occasions and has gone on to become a ‘special song’ for some lovers, brides and grooms who associated it with important moments in their lives. Well that’s just grand. Who am I to question such interpretations—or indeed tell those who think of it as their special song that it is not actually about everlasting love, but a transient rake on the make. It is surely not up to me to ‘burst that bubble’.

Of course this isn’t a real crisis of song writing confidence. I could knock out a tune and a line or two, and it would sound fine, catchy even; I am not lazy about doing that, just ambivalent. I wanted to sing a song like the poem ‘September’ (Hetherington 2011:3) even though no one would hear my kitchen performance. That was when the ‘lyrical future of nostalgia’ idea really impressed itself on me, dropping like a coin in a slot machine, saying, ‘what if’? What if I spin the barrels of the slot machine and see what bells come up? Well I did, but before I reveal the ‘what if’ outcome I need to tell you a story. (I will keep it short.)

Forty years ago a boy met a girl in Edinburgh. They both worked with the Civil Service. He was a local boy, son of a coal miner who had managed to get a job on the surface. She was the daughter of a docker from Belfast—40 years ago Northern Irish civil servants were allowed to work on the mainland for a few weeks to get some respite from the Troubles. Over a period of four weeks, the boy took her to Princes Street gardens, Edinburgh Castle, to a football match (local derby, Hearts and Hibs—he was a Hearts man), to a gig he was playing at the Edinburgh University Folk Club, and dancing; they liked to go dancing. After she returned to Belfast she asked the boy to come over for a visit, to ‘stay with her Ma ‘n Da’. So he did.

He travelled west from Edinburgh, caught a ferry to Belfast from Stranraer, and when he arrived she was waiting on the quay.

‘Was the crossing rough?’

‘No, it was fine. Good job too, I didn’t want to get seasick.’

‘Do you get seasick?’

‘Dunno!’ He’d never been on a boat before.

His feet hardly touched the ground when she said, ‘We’re going dancing, so we are …’ and with his small bag and guitar taken from him by her Ma, off they went. Magical, Belfast, Ireland, the land of the music he loved, the boy and the girl walking with a carefree shrug and a ‘who knows’ attitude. The night drew to a close; after a slow dance to a singer making a hash of ‘Rock-a-bye sweet baby James …’ (which they laughed at) they wandered, where to he didn’t know. They were just walking and talking, and then they came to her Ma’s gate where they were met by two squaddies (routine then, it was the time of the IRA; UDA and the Irish Troubles).

The younger of the two said, ‘We have your bag, get in.’ He gestured to an armoured vehicle.

‘Eh?’

‘We’ve been told to get you back on the ferry. It’s for your own safety. And for fuck’s sake, don’t mention what football team you support. Don’t you know anything? That information has already got you in trouble.’

Football? It shattered the air like a claxon. Heart of Midlothian (Hearts) had a Protestant allegiance; Hibernian (Hibs) were Catholic; it seems he had taken a Catholic girl to see his favourite Protestant team when they were in Edinburgh. Why would that matter? Well, in troubled, sectarian Ireland it wasn’t too difficult to figure out why he had suddenly been advised to leave. Yet it had never occurred to him — the boy with a Catholic mother and a socialist, coal-mining father, who had no church allegiance. Why would it?

The boy, with bag and guitar, arrived back in Stranraer, caught a train in Glasgow to Edinburgh and never saw the girl again.

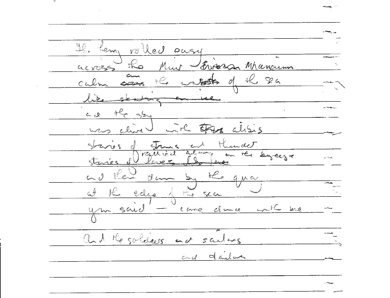

Fast forward 40 years: the boy, now a man, was looking through a box of scraps, lyrics he had carried from Edinburgh to Brighton via London (and a host of other places) and he found this:

He had written it on the boat on the way back.

And so now I was thinking again of the lyrical future of nostalgia. I can still remember the tune (miraculously) and so 40 years later I wondered what it would be like to finish the song. But before I proceed it is useful to add that in considering this idea of nostalgia, and indeed a lyrical future, the 40-year-old notebook only serves as an aide memoire. When Kundera wrote that the future of nostalgia is the ‘grammatical form that projects a lamented past into a distant future, that transforms the melancholy evocation of a thing that no longer exists into the heartbreaking sorrow of a promise that can never be realised’, it rang true; it opened up the possibilities of lives and encounters I could only imagine but in a way with which I could engage. The note above is only one means of demonstrating this physically. I have (as do we all) many others tucked away in metaphorical boxes inside boxes inside boxes, caught up as my history, secrets, thoughts and dreams, until I speak and reveal them. In the same way a song, once performed, will exist in the now, as Benjamin suggests in The Arcades Project; the historical object is reborn, as it were, into a present day capable of receiving it; of suddenly ‘recognising’ it and then musing on what could have been in the face of that remembrance or recognition.

Taking the first lines from the original piece was easy enough:

The ferry rolled easy

across the Muir Èireann

calm on the wash of the sea

and the sky was alive with alibis

stories of storms and thunder

rolling in on the breeze

and then down on the quay

at the edge of the sea

you said—‘come dance with me …’

So, okay, it’s not the poetic form of a W.B. Yeats but it serves a purpose because it is wrapped around a melody that does it justice. Thinking about it as a lyric is important. In a recent interview in this journal Paul Hetherington and Judith Johnson discussed Judy’s poetry, and she made the following comment:

Judy: … Though I didn’t plan for my poems to get longer and longer, when I look at my history as a poet, it seems like a logical evolution—to begin with small imagistic poems, then to develop an interest in narrative, then to write more expansive narrative poems, and then a verse novel, and then the novel in prose. But what’s interesting about that is the novel still feels as if it’s not quite my voice …

Paul: The prose novel?

Judy: The prose novel I think it is a different space. I think the verse novel space and the novel space are much more different than I thought it would be

Paul: What is that difference, do you think?

Judy: I think it’s to do with the size and the looser structure of the novel. And it’s to do with the lyrical density in the narrative poem. But it’s also to do with a kind of compactness of thought in poetry. The gaps in meaning that are left for the reader to fill in. Any form of poetry, even a verse novel, is different to prose. (Hetherington and Johnson: 2013)

I am interested in the idea that ‘[t]he gaps in meaning … are left for the reader to fill in. Any form of poetry, even a verse novel, is different to prose.’ The song has all the same potentiality of poetry, except that the performance attempts to make sense of the gaps in the meaning; the mood, the melody, the beat and the delivery both seek to add to and obscure those gaps. In the performance I will enclose with this paper I will try to make this plain, but for now let me turn to the lyrics. In those adolescent lines I wrote, above, the meaning starts simply,

The ferry rolled easy

across the Muir Èireann

calm on the wash of the sea

The singer is on the ferry, the sea is calm and he is crossing the Irish Sea. Little has changed from the original. I changed the Muir Mhanainn back to Muir Èireann because it’s the right change. I recall I took the words, Muir Mhanainn, from the map on the ferry (it means the Manx Sea). Calling it the Muir Èireann is a tilt at the Scots Gaelic because I am Scottish and I preferred that line to Irish Sea, or even the Erse Sea so there is nothing too much going on in singing the name except poetic licence. But the next three lines are a little more abstract (I hesitate to use the word complex):

and the sky was alive with alibis

stories of storms and thunder

rolling in on the breeze

The sky could have been cloudy and grey, or bright and blue, or dark and starry like Van Gogh’s, but being full of alibis was something that appealed due to the political situation in Ireland. This was the early 1970s; the time of the Troubles; and the ferry hosted a curious mix of travellers, all a little suspicious of each other. There were clusters, or cliques, eyeing each other up, and I got the sense that there was more suspicion than collective Irish consciousness on board. Of course, that may also be my nostalgic misplacement but I am not so sure that it is. Also, the internal rhyme of sky, alive and alibis had a nice ring to it when sung, so that too was a consideration. The ‘stories of storms and thunder’ are unambiguously about both sea journeys and troubled Northern Ireland: I am clear about that. I remember my own nervousness on the crossing, part excitement on the journey and part a venture into an unknown place that loomed large in newsprint for all of the wrong reasons. And surely all writers do this when they have entered the story. In The English patient, Ondaatje writes,

She entered the story knowing she would emerge from it feeling she had been immersed in the lives of others, in plots that stretched back twenty years, her body full of sentences and moments, as if awakening from sleep with a heaviness caused by unremembered dreams. (1992: 12)

Following on from the ‘dance with me’ refrain, then, the second verse became an imagined part of that same engagement:

And the soldiers and sailors

left their guns with the bailors

for the craic and the songs and the beer

and the night lied their alibis

and the stories of storms and thunder

riled drunken onto the breeze

down on the quay

at the edge of the sea

where you said, ‘come dance with me …’

But that was about then. Forty years after the first verse I followed my own train of thought of that time with what I remembered (in an abstract way). As we can see, it has become a romantic look at a point when the factions forgot their struggle for an evening, and the soldiers and sailors left their guns at the door; or, in legal parlance, with a ‘bailor’—a person who, by mutual agreement with the owner, takes control over or possession of the personal property of another for care, safekeeping, or use. Having passed their guns and tools of sectarian violence to the ‘bailors’, the soldiers and sailors enjoyed that ritualistic, cultural stereotype we associate with Ireland, ‘the craic and the songs and the beer’. It’s a simple trip to the pub, for laughter and fun, where ‘drouthy neibors, neibors meet’, to paraphrase Burns in ‘Tam O’Shanter’. It’s also an unashamed stereotype I use because all the Irish I know use it too. But of course the cliché of the craic hides the deeper stories, which I allude to when I wrote, ‘and the night lied their alibis’. I know what I mean by this but it is one of those lines I will leave to be interpreted. Make of it what you will, because each of us have some kind of political view.

Leaving this political view open also leaves interpretation open. Judy Johnson may have said that ‘[t]he gaps in meaning … are left for the reader to fill in’ but that doesn’t mean everyone shares the same views or will interpret the gaps in the same way. For example, as I wrote this paper, I found out a great hero of mine, Nelson Mandela, had just died. Here is what my government said when he was alive (I am ashamed to say):

Margaret Thatcher: The ANC is a typical terrorist organisation ... Anyone who thinks it is going to run the government in South Africa is living in cloud-cuckoo land.

Terry Dicks MP: How much longer will the Prime Minister allow herself to be kicked in the face by this black terrorist?

Teddy Taylor MP: Nelson Mandela should be shot.

At the same time, the Federation of Conservative Students wore 'Hang Mandela' badges. Imagine your own campus, and having to confront this. And, while Margaret Thatcher was making her thoughts known, Philip Larkin, a poet I admire, had already attended dinner with her, declaring himself a fan, as journalist Nigel Farndale reporting for The Observer (2013) wrote:

In 1982, London's leading literary lights gathered for a secret dinner party. The guest of honour? Margaret Thatcher … According to [Philip] Larkin, Thatcher said good- night ‘very civilly’. Two days later he was still in a state of ‘nervous and alcoholic exhaustion’. But he was clearly smitten. In a letter to his friend the poet and historian Robert Conquest, he wrote: ‘What a superb creature she is—right and beautiful—few prime ministers are either.’

Now of course, while I believe that her government’s record in South Africa and Northern Ireland is a damning blight on the UK as a civilised country, and I might have been more direct in the lyric I wrote, the truth is that I wasn’t really writing a political song but a song about a boy caught in time of the politics, which is a different thing—even if the two are inseparable. The trick was to make the politics known while attempting to make a stand. That is also where the chorus line comes from. Amidst the mayhem I wrote about something else:

down on the quay

at the edge of the sea

you said, ‘come dance with me …’

‘Come dance with me’ is a refrain that lingers throughout the song. In some ways I see it operating in the same way as the Cellist of Sarajevo by Steven Galloway. The siege may have been in force but the cellist played on.

It was when I came to write the bridge and the last chorus (I didn’t feel it really needed another verse) that I began to struggle a little. This is because I had decided to take the Milosz route (as shown by Kundera above) and anticipate the future of my nostalgia as seen through the eyes of another. It came out as a wistful wondering; do you remember the boy?

And you will stand at the edge of the water

throwing flowers into the sea

marking the place where we used to be …

down on the quay

at the edge of the sea - where we sang, ‘dance with me …’

Am I sure about this? I don’t know yet. It’s probably too soon for me to judge and it may change. As it stands, the song is still only an ‘apparatus for fabricating the allusion of reality,’ to further paraphrase Kundera (1995: 154). There is a historical first verse, with a biographical note; sparse lines scribbled on a lined paper of a journey across a stretch of sea, to be met and invited to dance. Nice as it is to recall, it is only a fragment of a story. Then in the next verse comes the imagined event on the quayside, one full of hope, the handing in of guns. I looked back at my younger idealistic self and the hopes that he held—indeed the hope I still hold for other conflicts, because the ‘Irish’ story is reflected in other stories and struggles; Palestine and Syria are two contemporary versions, for example. This is why I close with the ambiguous lines:

And you will stand at the edge of the water

throwing flowers into the sea

marking the place where we used to be …

This is the ‘imaginary me’ looking at the ‘imaginary you’, both imagining time passing as the trace of a story lingers. Troubled Ireland is the past and it is ‘where we used to be’, both the imaginary we, and the actual she and I; and it is where I imagine her still.

As a writer I have gone back as I go forward; I am projecting a nostalgic view of an event that didn’t actually take place—or if it did I have no way of knowing. Janus-faced, I am mirroring my present in the face of my past as I invent a nostalgic future. But I am fabricating that future, open-ended and without conclusion. The hope is that the ‘imaginary you’ lives a full, loving and healthy life; perhaps the odd memory of heady days in Edinburgh, circa 1972, but nothing more than that. Nevertheless, that is only a fabricated illusion of reality, wrapped up in hopefulness. It suits the song, it suits the mood and the time and the lyrical future I am projecting as nostalgia, but it doesn’t tell a fundamental truth. The real truth is that I don’t know whether she survived or survives still. Kundera writes that ‘the grammatical form of nostalgia’ is one that ‘projects a lamented past into a distant future, that transforms the melancholy evocation of a thing that no longer exists into the heartbreaking sorrow of a promise that can never be realized’ (2009: 107).

I am not so sure about this. The past I describe in the song is not a ‘lamented’ one but a historical one embellished with a little wishful thinking—hope might be a better word—followed by an ambiguous ending, refracted through différance (to paraphrase Derrida’s much abused idea), which is the only way it can be, surely? As Jen Webb and I once wrote:

Jacques Derrida has written, the ‘future, this beyond, is not another time, a day after history. It is present at the heart of experience. Present not as a total presence but as a trace …’ (Derrida 1978: 95). And this could be rephrased as ‘the future story’: an as-yet unread, unheard narrative, which is not situated in another time, a day after history, but is present at the heart of experience. Present not as a total presence but as a trace. The intimacies of such temporal and ontological connections, working in ancient and retold stories, can shed light on present contexts as they absorb the past and open up to the future. (Webb and Melrose: 2011)

The ‘flowers’ thrown ‘into the sea’ in that line could equally have been words, thoughts, dreams, laughter, regrets, no regrets and thanks. They are representational flowers, nothing more. Lilies for death, yellow roses for friendship, the odour of chrysanthemums in memory of a story we both read by D.H. Lawrence: symbolic objectivity that is equally subjective—how Janus-faced is that?

And before his voice finally gives out, here is the songwriter sitting at my desk singing, ‘Dance with me …’ as filmed by my teenage son and vlogger, Dan Melrose https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WWiOKw2wm68&feature=youtu.be

Dance With Me

The ferry rolled easy

across the Muir Èireann

calm on the wash of the sea

and the sky was alive with alibis

stories of storms and thunder

rolling in on the breeze

and then down on the quay

at the edge of the sea

you said—‘come dance with me …’

And the soldiers and sailors

left their guns with the bailors

for the craic and the songs and the beer

and the night lied their alibis

stories of storms and thunder

riled drunken onto the breeze

down on the quay

at the edge of the sea

where you said, ‘come dance with me …’

And you will stand at the edge of the water

throwing flowers into the sea

marking the place where we used to be …

down on the quay

at the edge of the sea—where we sang, ‘dance with me …’

Benjamin, Walter 1999, The arcades project, (trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin) Cambridge, Mass and London, Harvard University Press

Bertold Brecht, 1977, ‘Against György Lukács’, in Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Ernst Bloch, Bertolt Brecht, Georg Lukács, Aesthetics and politics: the key texts of the classic debate within German Marxism, trans. Ronald Taylor, Verso, London, 68-85.

Cooley, Peter 2012, ‘The travelling monostich: from Michelangelo in Rome to the leper colony in Carville, Louisiana’, Canberra, Axon, Vol 2, No 1

Gaughin, Dick http://www.dickgaughan.co.uk/songs/staves/stave-aefond.html, (accessed February 2014)

Hetherington, Paul 2011, It feels like disbelief, Cambridge UK, Salt Publishing

Hetherington, Paul 2012, Chicken and other poems, NSW, Australia, Picaro Press

Hetherington, Paul and Judith Johnson 2013 ‘Lifeline and reclamation’, Canberra, Axon, Vol 3, No 1

Hirsch, E 2006 ‘Mere air, these words, but delicious to hear’, at http://www.poetryfoundation.org/learning/article/177210 (accessed February 2014)

Kundera, Milan 1995 Testaments betrayed, London, Faber

Kundera, Milan 2009 Encounter essays (trans. Linda Aasher), London, Faber

The Observer (online) http://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2013/dec/07/dinner-with-margaret-thatcher-literary (accessed February 2014)

Ondatje, Michael 1992, The English patient, London, Bloomsbury

Pont, Antonio 2011 ‘Intimacy and Making: thinking of constellations of consciousness and the movements of invention’, Canberra, Au, Axon, Vol 1, No 1

Webb, Jen and Andrew Melrose 2011, ‘Intimacy and the Icarus Effect’, Canberra, Axon, Vol 1, No 1

Williams, William Carlos ‘Landscape with the fall of Icarus’, full text at http://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/landscape-fall-icarus (accessed 13 February 2014)