This piece offers up a methodology for writing about art — in this case an exhibition of jewellery titled She wants to go to her bedroom but she can’t be bothered (Lisa Walker, RMIT Design Hub Gallery, 2018). The approach centres around coming to language through somatic practice — or a speculative somatic encounter — as a way to get beyond concept and to another kind of language that is not already structured by extant paradigms of knowledge. The proposition is that thinking that is disconnected from the body is a narrowing of the mind, a narrow discursivity. The methodology attempts to start in the body, to listen to the body as a move toward an expanded response to the artwork. From this place we might discover another kind of art writing, another way of noticing different things, differently; themes come into view that may otherwise have been occluded; resonances and rhymes across experiences give rise to something novel.

Keywords: art criticism; somatics; Body-Mind centering

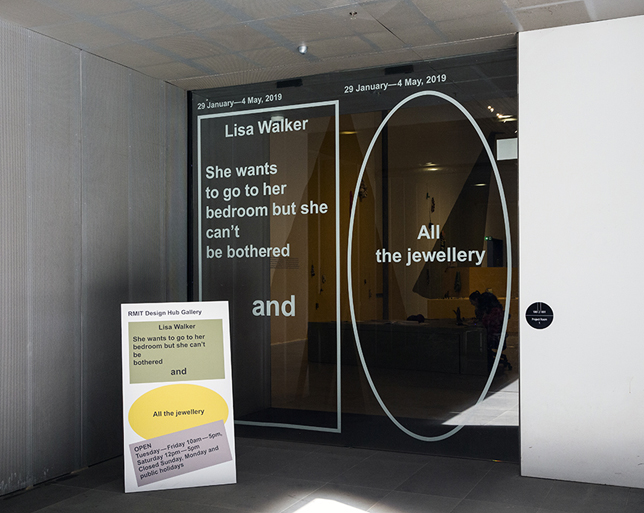

The day I went to see Lisa Walker’s exhibition She wants to go to her bedroom but she can’t be bothered (RMIT Design Hub Gallery, 2018), the gallery was closed. I had my face planted against the glass doors, at least to get a glimpse. Barthes came immediately to mind, perhaps because I had seen The Pleasure of the Text (1975) lying around near the photocopier in the office just before I walked across the road to Walker’s work, but also because ‘what pleasure wants is the site of loss, the seam, the cut … is not the most erotic portion of a body where the garment gapes?’ (Barthes 1975: 7-9).

The curators of the exhibition had invited a number of writers to lead a workshop, on the gallery floor, where we would propose to the workshop participants methodologies for writing about art. This group of writers was assembled by Lucinda Strahan, who had been running a number of similar workshops at ACCA, exploring a certain kind of ‘expanded writing’ methodology. This thwarted first visit to the gallery was in preparation for that. I’d go back another day.

A: my work is all wearable, though sometimes not particularly comfortable to wear.

(Walker et al 2019: 167) [1]

On my second visit to the gallery I walked about the room composing a methodology for writing about the exhibition. It didn’t happen all at once; it was a process that continues to unfold even now as I write this account for the reader. There are quite a number of parts to this story. I’ll try and list most of them here as a way to help describe the field we’re in — a kind of spatio-temporal grounding — as a way to help orient us as we move from one part to another.

Lisa Walker had an exhibition at RMIT Design Hub Gallery. Lucinda Strahan was approached by the curators, Nella Themelios and Kate Rhodes, to run a workshop with a group of writers, delivered to an audience of writers, on how to write about art. I was one of the writers; Loni Jeffs was another. At the workshop, where we each (six or so) presented an offering on how to start writing about art, Loni Jeffs and I noticed some resonance in what we presented. We were then invited to present this at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) where Loni and I composed our two pieces into one. We then transposed this work to page, for print. Concurrently, I participated in a Body-Mind-Centering workshop, which evolved as a fertile model through which to understand and play with the methodology I was developing for writing about art. These are the rudders.

Now I want to proceed in another way that keeps the different parts at play somewhat discrete, because I think that might give an appropriate sense of space that will allow me to find deeper resonances yet between the various parts of this story. I am attempting to find a form that doesn’t collapse the experiences and discoveries into a scholarly model I intended to escape with the development of the methodology in the first place. I have attempted to maintain the ‘expanded field’.

The ‘expanded field’ is a model Lucinda Strahan has been working with in relation to art writing (Strahan 2019). The nomenclature is fortunate because it resonates with the kinds of somatic practices that have led my own inquiry. For Strahan the expanded field is a move toward an expanded critical-creative art writing. For me the expanded field is where you arrive when you move attention deep inside the body and listen to the soma.

Back to the gallery: the colours, and irregular plinths, and uncanny objects gave a sense of a children’s adventure playground. This wasn’t a place of serious contemplation, but rather an invitation to play. I wanted to climb on the colourful blocks, crawl under and over the triangles, hop across one island of displays to the other. This was the invitation, but also certainly a restriction: it looks like a place of play, but the play can’t be enacted. Igniting this sense of exploration was key to discovering certain objects in the room. The eyes needed to wander up and down the walls — some objects mounted metres above my head, some objects partly occluded by the jutting out plinths. This arrangement was a set-up, an offering that was also a withdrawal: there was something there to see, but you couldn’t quite see it.

(Walker et al 2019: 185)

Though there were no ‘do not touch’ signs, one would assume, being in this kind of context, that climbing and touching were prohibited. But all the objects within reach were so touchable. Not only touchable but wearable. The objects are named: ‘brooch’, ‘pendant’, ‘necklace’, ‘chain’. This naming tells you exactly how it is to be worn, where it is to sit. And then: ‘domes’, ‘stacks’, ‘folds’, ‘wire experiments’. Not so clear. I want it in my hand, I want it on my cheek, I want new piercings in new places. But again, there were deterrents: the string on the ‘necklace’ (an Apple Mac laptop circa 1992, with a hole drilled in the corner where the rope was threaded) was thick and coarse, not for the soft skin of my neck, which it would burn and chaff. A display, a hiding, an obstruction, a showing off. Being denied entry into the gallery in the first place seemed now the perfect beginning: a promise of possibilities that could not be realised. The staging of jewellery-as-art sets up a desire fashioned through naming (jewellery), and at the same time a deferral of the promise through framing (art). I want to put these objects on my body, but I am not allowed.

(Walker et al 2019: 417)

The dynamic tension in the gallery, where offerings were presented and also denied, opened up spaces of imagination and speculation for the body. In this way it was a performative space, all this drama going on where my body was called to respond, but at the same time prohibited from doing so. I wanted to hold, touch, carry the jewellery pieces, but they were petrified in their spots as art objects, with a number and a dimension (L x H x W x D). Is this a joke? As if its dimension is fixed. Clearly each object has definition, is made of clay or metal or gauze, but each object held so many more possibilities for acting out its jewelleriness if it met with flesh. I’m not interested in accessorising. But my flesh would awake to new ways of moving through the world born at the site of chest meeting wire experiment, elbow crease meeting domes.

A: sometimes I’m quite amazed at a piece once someone else is wearing it, of course the piece looks the same, but the wearer begins to own it, claim it. It becomes almost more a part of them than me.

(Walker et al 2019: 277)

The gallery space did become a kind of theatre, where the writing workshop was eventually held. A poet, writer, theatre maker, critic, philosopher, stood beside a chosen piece and read out responses, provocations, suggestions for how to come to language about the exhibition. I danced. A group of listeners and observers sat in the middle of the gallery floor and took notes, asked questions, swivelled in their chairs to get a better look, to focus their better ear in the direction of the speaker.

(Walker at al 2019: 225).

In the gallery I was standing next to Loni Jeffs. It was our first meeting, and our standing next to one another was serendipitous, as this proximity of bodies and language illuminated interesting resonances across our responses to Walker’s work. After the event in the gallery, we were asked to submit our writing for a publication. Loni and I decided to further enact, on the page, the exchange and play we had found on the gallery floor. The pieces, together, work as a dialogue, or an interruption.

Loni says something about maps; mapping out the

space and where everything sits in relation to everything else.

I say something about a figure, moving, but ‘it’s not a dance routine.

She’s not a dancer. It’s not a performance.

Though the process is made public, and there are witnesses

to this process, it’s only a writer moving her body

as a way to come to language’.

Around the same time I found myself in an Embryology workshop, which comes out of the Body-Mind-Centring practice. The workshop essentially lead us to embody the development of an embryo from the moment before conception, to the moment of birth. When I say ‘embody’ I mean we were led through a series of exercises that had us leaping about the room and rolling around on the floor; imagine interpretative dance reverie. Another way of putting it would be: we somatised the development of the embryo.

Loni says something about meat and

something about ornaments.

And then I say, ‘we’re talking about objects here.

But in the first instance we’re encountering objects …

it’s the porosity of the body that I trust in this encounter.

The body wants to yield to the objects.

To yield is to make yourself available’.

My own intellectual and scholarly experience has been influenced by the Western philosophical traditions of phenomenology, affect theory, non-representational theory, and process philosophy. These could all seem useful frameworks within which to couch some of my interests here. But I have made a deliberate sidestep with this project. While I’m sure that I have embodied some ways of seeing and being in the world from the above list, I have deliberately left those books closed in this experiment.[2] I have instead opened up to the somatic practices that I find are much more open to wonder, and the possibility of something radically new (see Sheets-Johnstone 2009 on the ‘corporeal turn’). I am influenced heavily by my understanding and experience of traditional East Asian medicine and Tibetan Buddhism, specifically the Tantric lineage.[3] In these lineages the body is never separated from ‘what there is’ or ‘who we are’; it maintains what I see as the integrity of the body with the world, and of the body with the mind. If discursive thought is tension in the body (see, for example, Ray 2016), is it possible to think or write from soft flesh? This question sits at the heart of my turn to the somatic practices that have informed this project.

What is it really to listen, not constrict, contract, construct? How might we maintain an open curiosity that pays attention to the encounters that happen in the gallery, an attention that isn’t already conditioned even as we peer through the glass doors of the gallery? It may very well be an impossible desire, but here is the evidence of this experimentation. Here is the proposition that the experimentation into this way of encountering art, and writing about the encounter, happens through the body.

At the Body-Mind-Centering (BMC) workshop, I met a woman named Kim Sargent-Wishart. The trajectory of our relationship is very much a part of this story. Kim introduced me to her own work on the relationship between BMC and Tibetan Buddhism as a model for creativity (Sargent-Wishart 2012). She also explores the relationship between soma and word. From what I understand of her work, the stream of consciousness writing that she encourages after a period of guided movement (where Kim guides dancers through improvisational movement) is ‘a pathway to articulation in the immediacy of experience’ (Sargent-Wishart 2012: 140), an articulation of kinaesthetic sensation and somatic experience. The interest remains with the body; language serves to speak for the body. As we go on, we might see how the practice I’m describing here is a little different, in that we go into the body in order to think about the art object and find language for it.

(Lily van der Stokker, cited Walker et al 2019: 459)

As the embryo develops in the womb it grows many, many nerves, which offer the human body the potential for a vast range of movement. From the time we’re born, and start to develop outside the womb, continuing our exploration of our form and what it can do, nerves start to ‘prune’ themselves. The organism must do this because otherwise there’s too much possibility. As a matter of development, as a matter of finding a viable form with which to move through the world, the body itself starts to limit its own potential, limit the range of movement. I’ve been trying to imagine what an unviable human form might look and feel like. I wonder whether the nervous system remembers these other potentialities? Is there a vast expressive range in some memory of the body? On the one hand, a loss, already, so early on; and on the other hand, a trace, still, of the possibility of new gestures. There’s a third hand here: the need for limits.

A: no, I’m not.

(Walker et al 2019: 165)

The question above takes us on a trajectory from object to body to mind. But let’s stay on the body. Let’s go into the body, deeper without resurfacing to the narrowness of the mind. Descend deeper into the flesh. There are no ‘ideas’ there. The real question is: are you co-opting the people who wear your jewellery to move with the -ness of it?

I say: This is an experiment in ‘getting to know’.

Moving through the body, coming to language which

articulates the art object.

Loni interrupts, she’s quoting Aira Cesar (2018), she’s talking

about expansion, not in the fleshy kind I use this word,

but it chimes well in any case, an expansion ‘in all dimensions’.

Though Loni is talking about language, she’s talking about literature,

‘the motion is outward’.

I continue: I can speculate about the co-existence of

seemingly incongruent entities, and that entities can take

any form on a rhizomatic spectrum of the actualised, imagined,

forgotten, and the not yet.

In my journey as embryo, my favourite part was the stem cell moment. This is the moment when the cells can be anything, they hold all the potentials. They can be the limb, they can be an organ, they can be plasma. The workshop leader Christine Coleman says: some of the cells are ‘treasure cells’, that’s you, your uniqueness. And so while there is all this potential, and so much abundance, and even though we make three times more cells than we actually need, because we are in a relation, responsive always to the environments we are in/of, we balance permissions, potentials, possibilities and limitations, actualities — what actually arises as viable for all systems.

(Walker et al 2019: 393)

While the object-on-body can open up new ways of moving in an encounter between the two, let’s just call them both ‘bodies’ (see Gregg & Seigworth 2010), we could also see this as a restriction: the two bodies in their encounter must move in a particular way that makes both forms viable. Seen from this perspective they limit one another’s movement, they each determine a movement in the other in their relating. So while the pieces in the room could be conduits for my discovering new and other ways of moving, at the same time this may be the very limit to only a particular kind of movement.

But I’m only imagining what it might be like. I’m imagining the objects on my body and putting my attention in the space where my body and the object would touch. And then I extend my awareness into the shape of the object and deeper into my own body. And from this place I try to resurface to language. I’m not describing an affective response to the artwork, and this is also not a phenomenological account of what happened in the gallery. I would say it is a languaging of a speculative somatic encounter.

Pick a piece that’s pinned to the wall, or perched on a plinth. Use your haptic gaze to think/feel the texture, weight, temperature of the object on a part of your body. Think/feel means: put your mind/awareness in this place, the place where the object and your body touch; sharing boundaries, textures against skin, against metal, against fabrics that chaff together.

Allow this meeting to move you. Carrying, being carried, moving through the world differently now that you move together. Let it utterly transform the vocabulary of movement you have up to now relied on, or taken for granted. Discover a new way of moving/thinking/feeling through this somatic awareness.

What other imaginative, speculative work can you do to ‘know’ the piece through the body? Are there images in that somatic meeting between body and object? Can you language those images? But be careful not to resurface into the head. Write from those places in the body.

This process is a way of coming into the body, sinking down into the vast knowledge of the internal landscape. My attempts are to sink beneath cognition, beneath the need to structure experience with certain paradigms of meaning. What I find down there are different ways of experiencing and feeling/thinking. But are there words there? The words I’m looking for are the words of the fascia, words of our connective tissue. My somatic meditation teacher says: discursivity creates tension in the body. All tension in the body is discursive thought, which is the mind narrowing, not listening to what the body has to say. I’m trying to find a methodology that listens to what the body has to say, and trying to find a language that is not of that narrowing kind, but of the vast and soft tissue.

Loni quotes Adrienne Rich (2018: 484):

‘the ornament hung from my neck is a black

locket with a chain barely felt for years clasp I couldn’t open’

What I am really asking you to do is embody the

material qualities of the ornament.

It’s kind of like swallowing it.

And then speaking with your belly full of it.

Or you can swallow it down to your fourth toe

or your left earlobe.

Loni thinks of Cesar and literature as a ‘silver bridge’,

‘doing and not-doing, mystery, asymmetry’, she says.

Maxine Sheets-Johnstone advises that ‘what is essential is a non-separation of thinking and doing’ (2009: 2a). What sits as a foundation to this non-separation is, I think, an understanding of ‘thinking’ as a non-discursive event. And this non-discursive event happens via/in/through the body. Encountering the world, or ‘wondering the world’ with the body is doing it ‘directly’ (2009: 2b). The assumption here is that words are less direct, that by the time we come to language the experience has been mediated. I am wondering whether we can maintain some kind of open channel between the soma and the word; or at least pay close attention to this journey.

(Walker et al 2019: 197)

Walker’s answer to the above question is obfuscating. But the question is an excellent one. How do we find the bridge here? I am having to speculatively enact this bridge, speculatively embody the work so I might become a wearer from my position as audience. A suggestion, a titillation. This is the pleasure.

A: I think a person can be transformed if they wear a certain piece of mine

(Walker et al 2019: 287)

Coming into the body feels like touching a pre-verbal state. There’s a certain kind of sensitivity and liveness there, especially true for the embryo body. There are knowledges and experiences only the nervous system remembers. This move toward the expressive body feels like a move toward a fearless body. The fearless body is the free expressive body that taps into all of its early knowledges and potentials.

I am not a dancer. I don’t have to look good doing this. I have no dance language to structure my exploration for me. I think this is important — that I don’t have a formal or learnt vocabulary for my body. In some ways this is a lie; we all have lots of vocabularies that structure our bodies and how we experience them, how we move them. The point is that this thinking-in-movement has no aesthetic concerns for the dance or the body; it’s a movement into language. There’s a difference between practices that work to come to definition and meaning and structure; and somatic practices that simply listen to what is there, to what is unique in this encounter with these pieces of art, outside of things already known and determined. I want to see ‘what there is’, because this ‘what there is’ can be occluded when we proceed with concepts. Can I escape concepts through the body, relax the tension, and find language that maintains the softness and expansion? The dance with the object is partly a way to allow the material qualities and textures of the object their full affective power. But it’s more than this. It is a move into a deeper awareness, a deeper ‘knowingness’ of it (Sargent-Wishart 2012). It is from this deep knowingness that I wish to discover its language.

In desiring the object to hang about my neck,

I imagine it there, hanging, some parts of it dangling,

kicking out, kinking across my chest, long limbs huddling,

moving around and to the point. The joke is: soft steel.

It is soft, stuffed and puffing out like baby’s chubby limbs,

but pretending to be steel.

‘language lined with flesh’ (Barthes 1975: 66)

Loni says: body-object-process.

Three states of writing.

I have been calling to mind, here, a number of different spaces of encounter: the gallery, the womb, language. But what does this look and feel like when the encounter is speculative, when the body can’t actually meet the object, but must imagine it? Does this count? Is this space of speculation an opportunity for something different altogether which the actual experience of adorning with these items would not yield?

While enacting the moment that the embryo burrows itself into the uterine wall to feed and nourish itself, I get a sense of the beginning: we are utterly on our own, and utterly connected. A division of cells is a process of differentiation while still connected, always, by some fluid, some ocean, some membrane. A mirroring of one to the other. Different but exactly the same, but entirely different. I felt strength and agency to feed on whatever, but the thing that fed me was: mother. Agency and total dependence. The hunger drives it, and the mother provides. Being nourished and taking its nourishment. So much abundance. The embryo gets so big it has to separate, that is the moment when the placenta forms. The placenta is the foetus’ own DNA, as well as the mother’s. Bainbridge Cohen (2012) says: before we know ourselves as one, whole, undifferentiated, we are two. I speak of agency but this implies a centre. Is there another word I can use? — because the agency I speak of has no centre, everything is always in a relation, there has never been a moment of singular agency or choice, but only a connectedness where the seat of the ‘I’ is impossible to locate.

There’s a chemistry here, for certain; it isn’t just poetry; although some of it is only a speculation because we can’t observe the embryo and every part of its development directly. Is this just a fun metaphor? What is to be transferred, transformed, shared, removed, discarded, safeguarded, tended, cultivated, nursed, nourished, devoured, in this relation between embryo, body, movement, word, language? On the gallery floor the imaginative leap into the body and the art object led to another kind of noticing and experiencing — how the two interrelate, transform, and find other, novel ways of being and languaging their experience together.

My thanks to Christine Cole and the participants of EmbryoFLOW workshop at North Yoga in Melbourne in March 2019, for their sharing and insights that have inspired some of these musings here.

Also my thanks to Lucinda Strahan and participants in the public programme ‘How do we write about jewellery?’, March 2019, which was part of the exhibition All the jewellery curated by Nella Themelios and Kate Rhodes at the RMIT Design Hub , where some of this work was developed.

[1] Accompanying the retrospective exhibition of Lisa Walker’s work is the 2019 book An Unreliable Guidebook to Jewellery, edited by curators Nella Themelios and Kate Rhodes, where they include their interviews with Walker.

[2] It may seem that I am creating a break here between these traditions — crudely put, the Western and the Eastern. I do not want to maintain this break, and in future work understanding them together would be an interesting project. But this is not the work I will be doing on these pages, so I’ll leave this conversation here for now.

[3] I am a Shiatsu practitioner; this is a practice underpinned by Traditional East Asian Medicine. I also have a meditation practice from the Tibetan Buddhist, Tantric lineage. I am engaged in the ‘practising’ lineage, which means I am not a scholar but a practitioner in this field.

Bainbridge Cohen, B 2012 Sensing, Feeling, and Action: The Experiential Anatomy of Body-Mind Centering (3rd edn), Northampton, MA: Contact Editions

Barthes, R 1975 The Pleasure of the Text, New York: Hill and Wang

Cesar A 2018 On Contemporary Art, New York: David Zwirner Books

Gregg, M and Seigworth G (eds) 2010 The Affect Theory Reader, Durham: Duke University Press

Ray, R 2016 ‘Somatic meditation: Rediscovering the body as the ground of the spiritual path’, in H Blum (ed), Dancing with Dharma: Essays on Movement and Dance in Western Buddhism, North Carolina: McFarland, 187–91

Rich, A 2018 Later Poems, London: WW Norton & Company

Sargent-Wishart, K 2012 ‘Embodying the dynamics of the five elements’, Journal of Dance & Somatic Practices 4.1: 125–42

Sheets-Johnstone, M 2009, The Corporeal Turn: An Interdisciplinary Reader, Exeter, UK, and Charlottesville, VA: Imprint Academic

Strahan, L and Lacroix A 2019 ‘Writing in the expanded field’, Melbourne: ACCA, http://expanded-field.acca.melbourne/ (accessed 1 November 2019)

Walker, L, Rhodes, K and Themelios N 2019 An Unreliable Guide to Jewellery, Melbourne: RMIT Design Hub Gallery