There is shock in realising your parents are ageing. It is a state so easy not to acknowledge until there is personal and violent catastrophe — that abyssal line between before and after.

This essay is derivative from two other artefacts: a poem and an essay. I draw on both as a backgrounding and progressive consciousness, to write what I regard as the third instalment in the narrative surrounding the demise of our aging mother; our champion. Not only drawing on, but appropriating two ecological theories: abyssal line and slow violence, I argue that both metaphorically go to the heart of the loss and grief of losing a beloved parent, slowly. I argue that the slow expiration, or disappearance, of a person is an ecological event when the human body as a discrete environment slowly loses its agency as it ages, within its familial environment.

I have chosen the braided essay form as I wish to explore and develop my ideas around appropriating both ecological theories — abyssal line and slow violence — into my family’s personal loss of mother/wife/sister/aunt through a series of catastrophic moments, followed by slow demise in palliative care. The metaphor is clear in my mind — a cataclysmic event created a before and after moment; then witnessing this protracted breaking apart of a loved one, slowly and brutally. A braided essay lends itself to this telling, as Walker writes: ‘The further apart the threads of the braid, the more the essay resists easy substitutions and answers’ (Walker 2017). I wish to test her hypothesis with an inward familial gaze.

Keywords: abyssal line; slow violence; ageing; ecological event

It is 12.49 on 27 August 2018. Exactly six years ago, at this precise moment as I write, we lose our mother. Not entirely — she does not die — but something perishes within her, and is still withering, all these years later. It takes me five of these six years to realise this fact; not necessarily denial but it is surely a form of retro-fitting. A slow realisation; an undiagnosed mourning. For I never meet again the person who leaves my home at 12.10pm that day in 2012.

In one of those bizarre and catastrophic moments in life, our mother drives over herself with my youngest daughter’s car. We know it happens at 12.49pm, as this is where the hands of her smashed watch sit, just like in one of those Hollywood detective movies; one of those fictional ones. But this beginning of an end-of-life tale is anything but fiction.

***

Our father rings at about 1pm and in his gruff, staccato speech, asks me if I want to go with him.

Your mother has been in an accident.

What? How? Where? Yes … I stammer.

I don’t know, he spits.

He collects me and there is tension in the air; I imagine she has merely backed into a bollard and he is angry about that. That makes me angry at him. But then an ambulance screams past us at a T-section.

That could be her, he murmurs to himself.

Riveted, I look at him.

What the fuck, Dad … what do you know?

And he raises his voice, angry. Nothing. I don’t fucking know anything.

The car is full of white fury as we drive the seven minutes five kilometres to the shopping centre. They take an eternity.

We turn into the back road where she is, and there is an ambulance, with people and police milling. I go straight to her. No one knows what happened. No one sees what happened. The police say they believe it is a mugging.

She is dazed and bloody and broken, prone on the ground.

I travel with her in the ambulance but she says nothing, semi-conscious.

It takes hours at the hospital and our father and I stand sentinel, still not talking. At 7pm, a doctor tells us her blood pressure is dropping fast and she needs to get to a bigger hospital — we live 70 kilometres north of the city. I assume he means by ambulance, but no.

It is too serious, he says. We need to helicopter her.

I wonder at his use of a noun as a verb, and try to decide whether it is acceptable. I just look at him; and then at our father.

In his early 80s, our father’s face loses what little colour is left after these harrowing six hours. He knows what the doctor is trying not to say. We both know she is dying. We are not permitted to accompany her — there is not enough room in the flying noun that is now a verb. I rally my brothers who live in the city and they meet the helicopter. Gently, I take my father home and make him rest, and we wait.

My brothers ring and tell us she is alive, stabilising during the flight.

At midnight we hear she is still stable, and we go to bed.

And I am haunted by that watch face.

***

12.49pm. That is the moment; that is the precise moment creating a definite before and after. This moment is our family’s first abyssal line. The mother who exists before that moment — the one who champions us and defends us and loves us more deeply than seems humanly possible — never returns from any of the three hospitals she spends the following three months in, recovering. Instead, she becomes another, unknown to us.

An abyssal line. I like the sound of the word. It leaves my mouth with a haunting, harrowed tone. It sounds like falling. It tastes like doom. It is definitely treacherous. It conjures a precise image in my head — a divide. A foreboding one. The term is coined by Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Professor in the Sociology Department, University of Coimbra, Portugal. He writes of modern Western thinking as:

a system of visible and invisible distinctions, the invisible ones being the foundation of the visible ones. The invisible distinctions are established through radical lines that divide social reality into two realms, the realm of ‘this side of the line’ and the realm of ‘the other side of the line’. The division is such that ‘the other side of the line’ vanishes as reality becomes nonexistent, and is indeed produced as nonexistent. Nonexistent means not existing in any relevant or comprehensible way of being. (de Sousa Santos 2007: 1)

I am unashamedly appropriating this term for my own needs. But in his explanation I particularly am drawn to: ‘radical lines that divide social reality into two realms’. And this line: ‘Nonexistent means not existing in any relevant or comprehensible way of being’. Our mother crossed a line and entered another realm. And her reality — and ours — changes in that moment, as we are dragged near this space and place, looking in at her. Our foundation shatters as we watch. She is not here with us anymore; she is missing, over there, non-reachable. De Sousa Santos is writing of economic and social and political divides as a global paradigm which needs acknowledgement and remediation; a ‘moving on’ from. And all I can think of as I read his words is our mother, catapulted as she is after the accident (during the accident?) into a dementia that entraps us all, where remediation is non-existent within ‘civilised’ systems; within any system.

***

A policeman comes to the hospital that night, and separates me from the fray. He says he has to show me something, and opens his phone. There are images I vaguely recognise but am not quite sure what I am looking at. But there it is — my daughter’s car, reversing fast into one of the driveways of the car wash where our mother was cleaning it earlier; opposite where she is crumpled and bleeding when our father and I arrive.

But there is no one in it; the driver’s door gapes open, rocking backwards and forwards as the car abruptly, fiercely is caught, and stops.

Visually, it makes no sense, this haunted car.

Somehow, while the car is running and in reverse, but with the hand brake on, our mother steps into it with her left foot, and instead of securing the brake, she presses on the accelerator. She is pinned by the door as she grabs the steering wheel, locking the car into an extreme right-curve trajectory. It careens out of one drive way, backwards, the bottom corner tip of the car door that traps her gouging a hole into the opposite gutter as it smashes into it, opening it and suddenly releasing her. She slides downwards underneath the car and it runs over her in its frenzied journey, crushing her pelvis. It continues careening in reverse into the next driveway. Finally the hand brake stalls the car’s momentum, jerking it to an obscene and sudden stop.

It is an accident almost beyond comprehension, except I watch horrified, on CCTV.

The policeman tells me they are not charging her with negligent driving because she did no damage to property or person.

I think, except herself.

But we will be suspending her license, pending future driving medical examination, he says.

There is no future driving medical examination. She never drives again. She never really does most things again.

***

There is another moment that defines our family; another demarcating abyssal line with no remedy, within a space already divided. Our mother eventually recovers from the earlier accident well enough to come home, and then manages for several years, although her dementia, animated by her accident, is gaining more and more traction. She still tends to herself and manages small jobs our father gives her; she still laughs and pretends to do her Sudoku; she is still able enough to cheat at it, looking to the back for the answers. But like so many other elders in the community, our mother starts falling as her dementia flourishes, despite safety fixtures and stabilising walkers in place.

I see her fall once — it is delicate, a sort of crumpling, crumbling gentle sideways slide. Despite its slow motion affect, I do not get to her in time. But this time she is fine. Not even a bruise.

Perhaps we become complacent because her final fall is not gentle or crumbly; backwards in the dark, and smashing her head against a door jamb. But even at this moment, our father rushes and helps her up, and she continues on her business, getting to her bedroom and dressing for bed. Nothing is amiss the next day — perhaps she is more agitated than normal — but she sits with our father that Sunday night, watching the Men’s Final at the Australian Open in Melbourne on television. They go to bed as usual.

I know nothing about this fall until early the next morning, when our father rings and I hear the sob in his voice.

Something is wrong. Can you come?

I am with them in minutes. He is sitting on his side of the bed, reaching his arm behind and holding our mother’s hand. His head is in his other hand, and he is weeping, quietly.

I will never forget the sight of him.

Or her. Our mother is lying there, unable to move her legs but raving; seeing things on the walls; waving her free hand in the air, in time with a silent, spectral beat only she can hear; jibbering.

Once again an ambulance takes her away. We follow, and after waiting for an examination in A&E, the doctor takes us to a small room.

The fall has caused a massive and we think inoperable brain bleed, she says.

I fixate on the word massive, not hearing inoperable. Our mother is so small, always has been. How can she have anything massive?

OK, I say, what do we do?

Well, we are talking to Royal North Shore specialists, and we will get back to you. But you must prepare yourselves …

For the worst? I cannot remember what else is said exactly after that, but know this is an end of life prognosis. What I do remember are the tears, from nowhere, coursing down my face. And I remember thinking that suddenly, in another split second, we have crossed a line; another deeper abyssal line that changes everything as we know it. Again, I think to myself that we have become the family you see in all those B-grade Hollywood movies; the one in the small room off to the side where it is told this worst possible news.

I have to ring the boys, I tell our father.

No, wait until we know more … he trails off.

What are you talking about! I am ringing the boys, now. They have to know.

He nods, ashen-faced; crushed; crying. My words shatter his shock and his denial.

***

Once more, against all odds, she does not die. But again, clearly, much more dies within. Our mother is bed-bound; she cannot feed herself; she cannot talk. Or rather, when she does talk, it is often an aphasic scramble, with rambling sentences and concocted words. She suddenly hears herself, and stops, shocked. And closes her eyes. I watch her close her eyes, and the words of de Sousa Santos echo in my mind. I am drawn to his writings again:

What most fundamentally characterizes abyssal thinking is … the impossibility of the co-presence of the two sides of the line. To the extent that it prevails, this side of the line only prevails by exhausting the field of relevant reality. Beyond it, there is only nonexistence, invisibility, non-dialectical absence. (de Sousa Santos 2007: 1)

It is in the failure of her once eloquent vocabulary that her dialectical absence is profound, and we all feel it; she, at times, the most. But perhaps in the closing of her eyes our mother at least expresses some control over her ‘field of relevant reality’; she manages to shut the world out.

I have no idea what de Sousa Santos would make of my appropriation of his paradigm but the more I read him, the more applicable his notions become to not just our mother’s current existence, but to similar existences around the world. How to compare the life before to this life, non-lived? He analyses his abyssal thinking historically and colonially, then draws on the current geopolitical landscape, choosing Guantánamo as an example:

Guantánamo is today one of the most grotesque manifestations of abyssal legal thinking, the creation of the other side of the line as a non-area in legal and political terms, an unthinkable ground for the rule of law, human rights, and democracy. (de Sousa Santos 2007: 5)

He qualifies by writing that Guantánamo is not an exception, stating that there are ‘many other Guantánamos, from Iraq to Palestine and Darfur’. He then digs deeper:

More than that, there are millions of Guantánamos in sexual and racial discrimination both in the public and the private sphere, in the savage zones of the megacities, in ghettos, in sweatshops, in prisons, in the new forms of slavery, in the black market of human organs, in child labour and prostitution. (de Sousa Santos 2007: 5)

And I would add to his list of sociopolitical realms: the elderly dying slowly, brutally, within their dementia.

***

We must secure a nursing home place for our mother, something our father swore we would never do, intent on caring for her himself. But he can no longer; this much is clear. We find one; it is beautiful and calm, and the director is an extraordinary woman. There is compassion and gentleness and vigilance.

And there is ‘slow violence’ all around. For this is a place where you do not recover; this is a place where you never get better. This is a place where you die, slowly. Bodies degenerate and dwindle. Physically, mentally, emotionally, psychically.

There are three definitions for the word ‘ecology’ in the dictionary; one for the singular and two for the plural. It is:

a branch of biology dealing with the relations and interactions between organisms and their environment, including other organisms; the set of relationships existing between organisms and their environment; and the set of relationships existing between any complex system and its surroundings or environment.

So the slow death of a discrete human must constitute an ecological event; an organism turning on herself, killing herself as neurons are coated in plaque and synapses fail to connect. Slowly, the brain shrinks as cells die. The normal human brain contains 100 million brain cells connected by 5 to 10,000 synapses (Dementia Australia 2017). As synapses fail to transmit messages to the brain, functions are lost. This begins in its outer edges, slowly, creeping-ly moving deeper and deeper into the brain, into its heart. This slowness is not kind, and it is not gentle — it is terrifying and ruthless, its violence unnamed, ‘incremental and accretive’ (Nixon 2013: 2).

As this internal, slow, human obliteration metaphorically imitates the Earth’s lingering Anthropocentric demise, I hear its mimetic prowess echo throughout the writings of eco-critic Rob Nixon.[i] I marvel at his breadth and scope as I read his words — about environmental degradation and social injustice; about climate change and a thawing cryosphere, deforestation and acid oceans; about toxic waste and the aftermath of wars — slowly, silently, invisibly wreaking havoc in the world today. He writes of:

A violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all. Violence is customarily conceived as an event or action that is immediate in time, explosive and spectacular in space, and as erupting into instant sensational visibility. (Nixon 2013: 2)

He talks about engaging ‘a different kind of violence, a violence that is neither spectacular nor instantaneous, but rather incremental and accretive, its calamitous repercussions playing out across a range of temporal scales’.

And then I read his phrase ‘the long dyings’, and gasp out loud.

The long dyings — the nursing home where our mother is now suspended is full of long dyings. As are nursing homes and homes around the country; around the globe. For this is what is happening to our mother, this ‘slow violence’ of dying from dementia; a loss of agency and faculty; the lingering degradation of her brain cells inflicting a protracted break down of her organs, deliberately and unstoppably. Quantum physics has us believe that the human body is made up of particles from the rest of the universe; that we are one and the same; a microcosm of that huge macrocosm. Then this dying is certainly an ‘environmental calamity’; an ecological disaster. This way of dying.

***

Daily our mother is moved by a small hydraulic lift to and from her bed, into something called a tub chair, encapsulating and holding her. She looks cosy there. Every day, our father visits. He pushes her out onto the deck if it is sunny; he feeds her mandarin and grapes; he feeds her lunch. He holds her hand.

They do not speak much.

One day he points to her watch (he buys her a new one to replace the smashed one) and asks her the time. She stares at the watch on her wrist, then shrugs. He points to the 2, and she says two.

Yes, he says. He points to the four.

Eight, she says.

No, he smiles. No. It is a four. But it means 20 past 2.

Does it? She looks at him, fascinated.

He smiles and pats her hand, once more covering it with his.

That’s all right, darl. It’s all right.

Our mother looks at me, and shrugs.

On another day, she looks at me close-up, deeply into my eyes. She then turns to our father and says: Who is that?

That’s our daughter, he booms. Sometimes I feel he thinks if he is loud enough or stern enough, our mother, his wife, will return to us.

I say: Dad, it’s all right.

The next day I ask our mother: Who am I?

And she says, smiling triumphantly: My sister!

I hold her hand and tell her: That’s close enough, Mama.

Sometimes people say to me: Well, at least she does not know what is going on.

This is an excruciating statement, as it only diminishes her further; and as it is not true. Visiting one day — it is a wintry Saturday afternoon — our father is also there. It is time for me to leave and I kiss her gently on her forehead and whisper in her ear, as I always do when I leave, I love you.

Where are you going? she asks, her voice paper-thin.

I am going home.

Take me with you. Please.

O Mama, I can’t. I am so sorry.

A single tear forms at the outside corner of her right eye. It slips slowly down her cheek, pushed by more and more gentle tears.

I just want to go to bed, then. Just put me back to bed.

Her lucidity in that moment is palpable; her sadness and depression all too real. I know she knows. Knows clearly. Again, my face is wet with tears and I look to our father.

He is also crying.

He tells me: You know, every single day when I leave this place, I just feel sad. Totally sad.

He is 85 and knows this is no way for our mother to live; no way for him to live.

Sixty-three years of marriage and now this; this witnessing; her anguish; his vicarious suffering.

***

Nixon asks: ‘How can we turn the long emergencies of slow violence into stories dramatic enough to rouse public sentiment and warrant political intervention’ (Nixon 2013: 3) — a polemic that is, really, a manifesto. And this is where my anger flares.

Reading an article written several years ago by a young Sydney doctor, I immediately act. The article tells of the distress of young doctors in A&E when families cannot let go of their elderly, injured or ailing loved ones; when there is desperation not to lose them, with no thought of intervention ramifications. The doctor, telling of how she and her colleagues return to their own homes, traumatised by the families’ tormented decision making processes — the wrong decisions arrived at — regularly in her hospital; and a plea to gather an Advanced Care Plan from all elderly relatives; to be prepared, with their wishes at our fingertips.

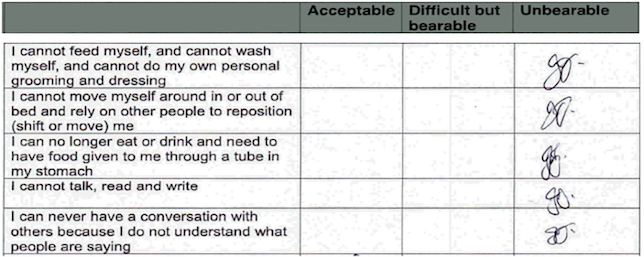

So I do it. I download two forms and race to my parents’ home with them, and the article. I ask them to read the article, and then fill in the plan. At this stage, our mother is still able to manage the reading and comprehension of the form — just. And so she takes her time and fills it in. But now I do not know what good it has done anyone; certainly not her, as she is living, by her own signature, in an unbearable state. Certainly not me, nor our father nor my brothers: we have in black and white what she never wanted, and can do not a thing about it:

The only section above not applicable to our mother’s life now is the third point; as yet, she is not fed through a tube; and I know, never will be. So, I argue, this is a microcosm of a slow and violent demise; this is an ecological personal disaster; this is an ‘environmental calamity’ (Nixon 2013: 3) of an intimately particular kind.

The rational next development stage of this argument leans into the beginning of a euthanasia discussion; or perhaps it is closer to the end of a euthanasia debate, and decisions must be made. Nixon writes: ‘We need to account for how the temporal dispersion of slow violence affects the way we perceive and respond to a variety of social afflictions’ (Nixon 2013: 3). Again, unashamed appropriation, but his words metaphorically deliver the verdict — if it is time to deal with the social, political, geographical and climactic disasters surrounding us, it is time to drill down to the personal and intimate ecological disasters also. This must be a parliamentary conscience vote, driven by electoral consensus, not personal evaluation nor political party line; and the separation of Church and State assiduously upheld. Following through further, if a rational debate affirms and confirms a rational and civilised outcome, the right to die would be ours.

And so, and so, and so …

… when would we uphold our mother’s wishes? By her own hand, her life is unbearable. She signified this when she knew what she was doing; what she wanted; how she envisioned her future life – when she was compos mentis. But at what point do we, her loving family, rally and carry out her wishes, if we could?

Patricia Hampl calls the braided essay — the form within which I am immersed at the moment — ‘a destination with metaphor torque’ (in McKinley 2018). And this is where I find myself, with no answers. My rational side wishes our mother’s lost-ness to end, quickly, peacefully and gently, with as much love as we can make her understand. But to assist, if we could? I try to imagine how to do this? The civilised action; the rational course. Like this essay, I twist and turn mentally during my visits with her and during sleepless nights because of the ‘unbearableness’ she endures.

Audaciously I claim to believe in a person’s right to die. I want this right. I believe our mother rationally wants this right.

If only, if only, if only …

… she could make the decision herself now.

But if she could, there would be no reason to. Her heart is strong. Her vitals, normal. Apart from the dementia, there is no disease. Nothing to fight. Nothing to sacrifice. Just a peaceful slide into her end of life; no violence. Perhaps, just falling asleep and not waking again one day, a dream scenario for those we love. And so, around in circles we go. There is no answer, yet. As de Sousa Santos writes so convincingly:

It is in the nature of the ecology of knowledges to establish itself through constant questioning and incomplete answers. This is what makes it a prudent knowledge. The ecology of knowledges enables us to have a much broader vision of what we do not know, as well as of what we do know, and also to be aware that what we do not know is our own ignorance, not a general ignorance. (de Sousa Santos 2007: 19)

And so, we search for answers; we search for knowledge, some meaning, some goodness, to derive from this unsustainable yet protracted dying. Some sense and value to this time.

***

Our mother’s place in the space at the centre of our family home, at the heart of our family, is no longer hers. Nixon writes of ‘Attritional catastrophes that overspill clear boundaries and space … places are rendered irretrievable to those who once inhabited them’ (Nixon 2013: 7). Demonstrably, she is incapable now of standing there. She does not inhabit this well-worn gap any more; has not, for years. I know this is catastrophic to her and, in so many ways, to us.

And then, something else begins to happen. The unthinkable, really. For over there is our father, holding her hand every day; feeding her; going back home, surrounded by her possessions, her scent, her absent presence. Our father undergoes a slow psychic violence himself, daily creating a life from the fragments of hers. We watch as something begins to build, from the fractured existence of his wife of more than six decades. We witness his tenderness; his despair; his anger; his sorrow. And a new dynamic arises between him and his grown children; his grandchildren — deep conversations never had before; time spent with him, and only him; daily chats, previously, never a part of our days; kindnesses offered and accepted. Laughter. His stories, untold, suddenly remembered and recounted. Tears; many tears. A gentleness where there was mostly always a critical silence; a relationship phoenix arising from her wreckage.

One that will endure when she is gone; upholding him in his grief, and us.

And this, her final gift.

[i] Professor of English at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. His book is Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, published by Harvard University Press in 2013; his text won 2012 American Book Award, among other awards.

Dementia Australia 2017 ‘Alzheimer’s Disease’, https://www.dementia.org.au/about-dementia/types-of-dementia/alzheimers-disease

de Sousa Santos, B 2007 ‘Beyond abyssal thinking: From global lines to ecologies of knowledges’, Eurozine (29 June): 1–42, https://www.eurozine.com/beyond-abyssal-thinking/ (accessed 27 August 2018)

McKinley, H 2018 ‘Daydream believer: An interview with Patricia Hampl’, Creative Nonfiction 67, https://www.creativenonfiction.org/online-reading/daydream-believer (accessed 28 August 2018)

Nixon, R 2013, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press

Walker, N 2017, ‘The braided essay as social justice action: Between the lines’, Creative Nonfiction 64 (Adaptation), https://www.creativenonfiction.org/online-reading/braided-essay-social-justice-action (accessed 2 July 2018)