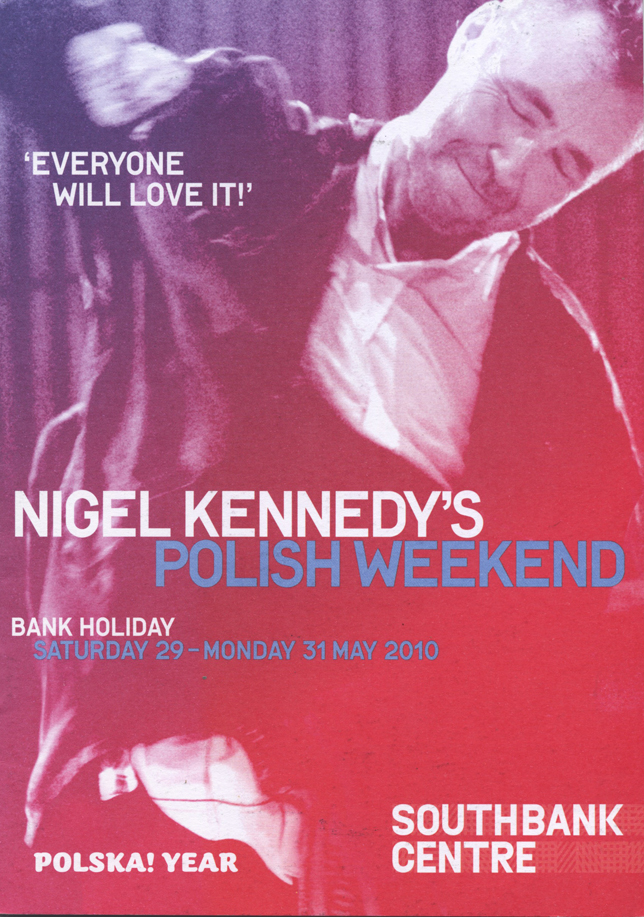

In 2011, British violinist Nigel Kennedy staged the most outrageously ambitious event of his career to date: a three-day ‘Polish Weekend’ at London’s Southbank Centre, celebrating Polish music and culture. Kennedy himself played in eight of the 13 concerts. At the heart of the weekend was Kennedy’s ‘World Cup Project’, a screening of the legendary England v Poland football match of 1973, in which England—for the first time ever—failed to qualify for the tournament. Kennedy’s band engaged with a group of Polish musicians in providing a semi-improvised soundtrack to the otherwise silent footage. Paul Munden, who is writing a hybrid biography of Kennedy, was present at the event, which demonstrated Kennedy’s profound association between music and sport, and informs a key chapter of the book.

Inside, outside

All this, I am aware, sounds fanciful and is perhaps misremembered, written up. But if it is: well, that is the spectator’s fate—we watch but in the end we have to guess. (Hamilton 1993: 12–13)

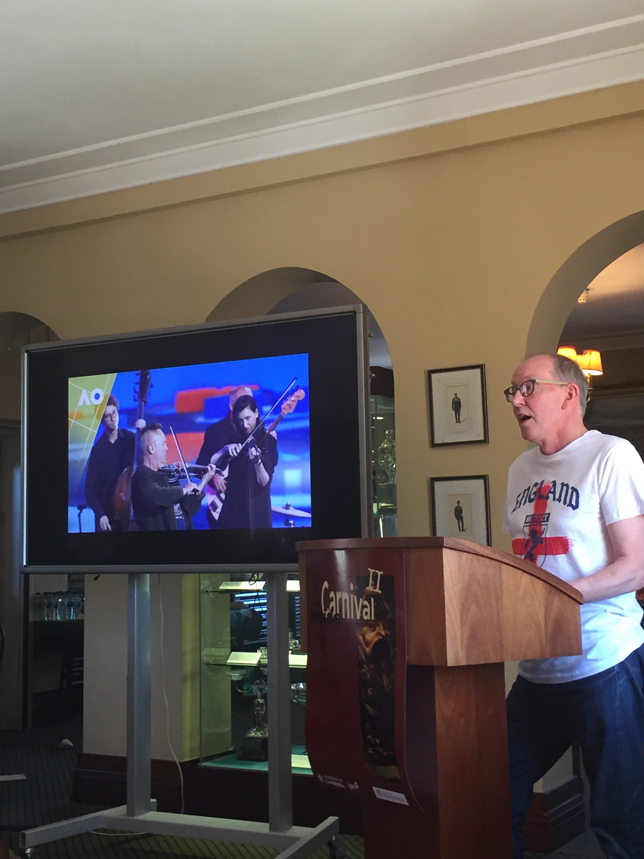

On the day that the University of Winchester hosted ‘Inside/Outside/Carnival II’ (Wednesday 27 June 2018), England was in rare carnival mode. The 21st FIFA World Cup was underway and the young England team was performing remarkably well. I had already planned to bring the world of football into the symposium, but there was now additional impetus for my presentation inside the world of academia to reflect what was colouring the street life outside, where cars were adorned with English flags—as were pubs, their clientele often in football shirts. These were of course predominantly England shirts, but not exclusively so, particularly in more multicultural cities, where displays of partisan support were proving to be thoroughly good-humoured. There were major upsets among the tournament results; anything, it seemed, might happen. And it all took place in the hottest English summer for over forty years. I decided that I needed an England shirt in which to make my presentation, but the official England shirts were not readily available in Winchester that morning; luckily, the cut-price clothing store Primark provided an England T-shirt for a mere couple of pounds.

My presentation, which this article attempts to capture, delved into a particular football match of 1973, a match that quickly acquired ‘legendary’ status. (Such epithets may seem overblown, but there were many at the symposium who recalled the match; not many football games linger so long in the communal mind.[1]) The match took place at Wembley on 17 October, and was broadcast live on ITV with Hugh Johns and Billy Wright commentating. In the studio before kick-off, TV pundit Brian Clough (always a controversial character[2]) was calling Polish goalkeeper Jan Tomaszewski a ‘circus clown in gloves’ (Bevan 2013: n.pag.); at half-time he still refused to retract his comment, but it was Tomaszewski who turned the whole match on its head, ‘enter[ing] football folklore with a virtuoso, if unorthodox performance’ (ibid.).[3] The England team included sublimely gifted players such as Mick Channon and Alan Clarke, but they just couldn’t get past Tomaszewski, who dived at Clarke’s feet to make a save in the early minutes and only found out later that he’d broken five bones in his left wrist. Tomaszewski comments: ‘They were frozen during the game and the adrenaline meant I did not feel the pain’ (in Bevan, ibid.).

It was an extraordinary match, totally one-sided, with England having 36 shots on goal, Poland only two. Two England goals were disallowed, one by Mick Channon for no apparent reason. But football is cruel: the match ended in a draw. England failed to qualify for the first time ever, and Sir Alf Ramsey, hero of 1966 when England had won the tournament, was sacked.

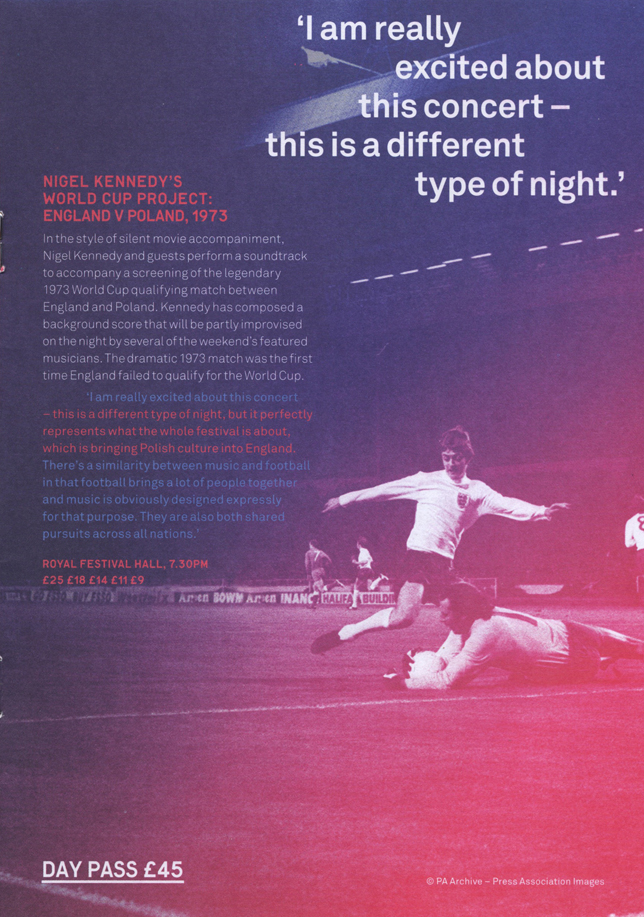

Clips from the match are available on YouTube (one with over a quarter of a million views) but it’s unlikely that the match is much re-watched in its entirety. In 2011, however, Nigel Kennedy provided that opportunity within his Polish Weekend at the Southbank Centre in London, a festival curated by Kennedy to coincide with the 200th anniversary of Chopin’s birth[4] in what was being dubbed ‘Polska!’ year.

The Polish Weekend

It was a ‘long’ weekend in more ways than one, extending into the May Bank Holiday Monday, with Kennedy scheduling 13 concerts within the three days—and playing in eight of those concerts himself. ‘I wanted to bring some Polish culture over to London and make the Southbank Centre into a miniature Poland for a while’ says Kennedy (in Brown 2010: n.pag.). Kennedy had been living in Krakow for nine years and felt that he had benefited enormously from the range of live music prevalent in Poland. For one of the concerts he assembled ‘Nigel Kennedy’s Chopin Super Group’, which improvised on familiar Chopin pieces (and was the first and only time I have witnessed an elderly lady jump out of her seat with alarm). The daytime events were followed by ‘Nigel’s Front Room Late’, jazz sessions that went on as long as the Southbank Centre could possibly allow, with (selected) audience members involved on stage. As Adam Sweeting wrote for theartsdesk (2010: n.pag.), ‘the timetable had been ripped to shreds by the end of the opening Saturday’. It was exhausting just to watch it all, which I did; but it was exhilarating too.

The centrepiece event, Kennedy’s ‘World Cup Project’, took place on the Sunday evening in the Royal Festival Hall. On the previous evening Kennedy had given it a plug: ‘We have no idea how it’s going to work’, he said, ‘so if you want to see a total fucking mess, do come along.’ It was originally a ticketed event scheduled to take place in the main concert auditorium, but Kennedy made a late decision to stage it in the foyer as a free event (with tickets refunded) in order to create the atmosphere he was after: the foyer backs onto the bar, and the whole place was draped with football flags and banners, with tables set up cabaret style.

It was very late getting started. Marshall Marcus, the Southbank Centre’s head of music at the time, came on to thank us for our patience and assure us that things would be underway soon. ‘There’s just one problem’, he said. ‘He’s called Nigel Kennedy.’ One got the impression that the violinist was seriously trying the patience of his hosts, though I’m not sure the audience was too worried. Drinks were to hand, and delay only added to the sense of occasion and anticipation. Meanwhile the stage was filling with an almost implausible array of kit. Not only was Kennedy to be joined by members of his own Orchestra of Life, this time with electrified instruments; many other musicians featuring in other concerts were also involved. It was, essentially, Kennedy’s ‘English’ team pitched against Polish rivals in a collaborative musical act of commemoration.

On the big screen behind (and on additional monitors to the side) the fateful match was then replayed—without the commentary (although at one stage Barry Davies, the original commentator for the BBC’s highlights had been rumoured to be taking part). The soundtrack was instead that of the musicians onstage engaging in semi-improvised contest for the full ninety minutes. It was an event beyond any ready comparison—except, perhaps, to the bewildering nature of the original match. There was, of course, one crucial difference: in Kennedy’s re-play the final score was a foregone conclusion; it was the music that provided the unpredictable drama.

Was it the chaos Kennedy himself had predicted? There were chaotic elements, certainly, but there were clearly structural principles involved. Each group of musicians deployed various themes, some of them familiar from other concerts or recordings. Kennedy, for instance, used melodies and riffs from his recently recorded album SHHH! (2010); he was countered by a particularly high energy performance by the Polish violinist Sebastian Karpiel-Bulecka, whose band Zakopower had played the previous day, and made use of material some of us had already heard. That made sense, in that footballers too bring highly practiced moves to their game. There were managerial hand signals involved in letting the other musicians know where to head next.

Kennedy was wearing his Aston Villa football shirt, as he so often does for anything other than classical performances[5] (this was another reason I wanted to make my presentation in a football shirt) and there were Villa banners as well as the national banners dressing the arena. To followers of Kennedy, this came as no surprise, but the obsession needs explaining here.

Kennedy and ‘The Villa’

Until recent times, Aston Villa Football Club had a pretty dignified history; in Kennedy’s words it was ‘the greatest team in the world before American and now Chinese ownership’ (2018). Founded in 1874, it was a founder member of league football in 1888. It’s the Aston Villa stadium that gets mentioned by Philip Larkin in his poem ‘MCMXIV’ (1971: 28):

Those long uneven lines

Standing as patiently

As if they were stretched outside

The Oval or Villa Park

Kennedy’s connection stems from 1964, the same year that he gained a scholarship to the Yehudi Menuhin School. He had lived with his mother in Brighton until then. Now he was sent away to boarding school, and his mother remarried and moved to Solihull, near Birmingham. It was Villa Park where he found a new sense of home and belonging, as so many do in joining a tribe. And loyalty to the tribe is then paramount. Playing at the BBC Proms in 2015, he drew the line at joining in the performance of ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’, pointing out that it was a ‘Liverpool song’. That comes across as rather harsh, but in his book, Always Playing (Kennedy 1991), he shows great respect for Liverpool fans, who had to endure the Hillsborough disaster of 1989.[6]

Many find such a sense of belonging; it is the extent to which football impinges on Kennedy’s musical performances that is altogether more startling. His Facebook biography page gives an example:

When Villa won the European Cup in Rotterdam in 1982, Kennedy was playing a concert in Germany. He stopped the concert and put up a giant screen so that he and the audience could watch the match before continuing with the music. ‘It was the right result that night’, he said. ‘And the crowd enjoyed both the music and the football’.

His latest Gershwin recording (2018) features ‘Rhapsody in Claret and Blue’ (the Villa strip); his business card sports those very colours and his electric violin is similarly customised. Even his BMW and house in the Malvern Hills were decorated to match. That might be considered an affectation, but Kennedy is open about the depth of the obsession:

One time I took two years off the violin to watch the Villa, and I used to watch the Villa, the Villa reserves and the Villa youth team, every week ... some people would call that wasting your life. (Kennedy 2017b: n.pag.)

On his Kafka album of 1996, the track ‘I believe in God’ is built around the football chant, ‘Ooh Aah Cantona’, except of course that he changes ‘Cantona’ to the Villa player ‘Paul McGrath’.

When Kennedy married a Polish wife and moved to Poland, he adopted Cracovia as a second allegiance. Like Villa it’s one of the country’s earliest clubs. When the Polish Weekend ‘match’ was staged it was, in a sense, Kennedy against Kennedy.

All of this is clear indication that, for Kennedy, football is a personal passion equivalent to music, and that he sees no reason to keep them apart. The title of his autobiography, Always Playing, might refer to either.[7] When talking about rival Polish composers Karlowicz and Mylnarski he immediately reaches (jokily) for a football metaphor: ‘Like Krakóv’s two football stadiums ... very close together, but very far apart’ (Allison 2007: 39). But he goes further, with statements about the relationship between music and football, and extending this to sport generally.[8]

I sometimes liken music to competitive sport. You see the great sportsmen and they are continually trying to improve. Even when they get to number one, they are never satisfied, they want to do more. Well, so do I. (Kennedy 2017a: 7)

In the Polish Weekend programme (2011: 7) he wrote:

There’s a similarity between music and football in that football brings a lot of people together and music is obviously designed expressly for that purpose. They are also both shared pursuits across all nations. (also in Brown 2010: n.pag.)

‘For me there’s an important correspondence between 40,000 people in a football stadium all wanting the same thing, that mass consciousness, and the performance of music.’ (Wallace 2000: 26)

More significant still are comments about directing, as in Always Playing. With a scathing attitude towards most conductors,[9] Kennedy states: ‘Up until the 1960s there was the same lasting allegiance between a conductor and his orchestra ... just like a good manager and his team’ (1991: 87–88). And as he said to Peter Culshaw, in the run-up to the Polish Weekend: ‘I’m a player-manager, I get on the field and direct the action’” (in Culshaw 2010: n.pag.).

The beautiful game

It was the Brazilian footballer Pelé who, in 1977, made ‘the beautiful game’ a popular, recognised reference to football, though HE Bates would appear to have been the first to use it, in a Sunday Times article titled ‘Brains in the feet’ (1952: 4). As that newspaper article indicates, the ‘brainwork’ of football is not of a cerebral or academic nature; it is instinctive, and Kennedy—despite his substantial musical erudition—clearly favours an equivalent brainwork (and beauty) in music. A further, frequent reference, in describing football of the highest quality, is to poetry—and not just as an off-the-peg metaphor. In his contribution to the Poetry Foundation website, ‘All Great Soccer Players Are Poets’, Duy Doan (2017: n.pag.) comments:

How often does Messi, for instance, with the game in the balance and his team depending on him to make the difference, summon the most imaginative, most beautiful solution possible? It’s almost as if he doesn’t know how to play any other way. When given the opportunity, Messi always opts for the memorable.

Perhaps the most astonishing comment of all comes from Eric Cantona, who famously said: ‘I will never find any difference between Pelé’s pass to Carlos Alberto in the final of the 1970 World Cup and the poetry of the young Rimbaud’ (in Hind 2009: n.pag.).[10]

Writing about Kennedy, I have been influenced by how the poet Ian Hamilton, in his book, Gazza Agonistes, has written about the footballer Paul Gascoigne (‘Gazza’), another sublimely gifted but difficult character, ‘a kid who has never really had time to grow up’, to use Hamilton’s words (1993: 98–99). The same might be said of Kennedy, whose scholarship to the Menuhin School, with all the expectations that accompany such a privilege, cut short any ‘normal’ childhood.

Kennedy became friends with the England football squad when he travelled with them to the 1990 World Cup in Italy. There is a YouTube video of Kennedy entertaining the players, and it is fascinating how Gazza, who was the creative genius but also the maverick in that squad, is the one who is most clearly entranced. Gazza was often savaged in the English press, but in Italy things were different. The Italians were strangely tolerant. In Gazza Italia, an expanded version of his original text, written in the run up to the 1994 World Cup, Hamilton writes: ‘In Italy... they regarded his nuttiness as an important aspect of his gift—and the gift was what mattered most of all’ (Hamilton 1994: 115).

Hamilton approaches his task as fan—both of football generally and of Gascoigne as an individual, and that’s not the same thing as writing a hagiography. He says: ‘Most soccer fans need to get hooked on the fortunes of a single player’; ‘you have to be part yob, part connoisseur’ (ibid.:13).

In the same way that Gazza’s indiscretions were simply ‘part of the package’ for the Lazio supporters, Kennedy fans are mostly willing to treat his more reckless tendencies with a similar shrug. Others of course react in horror, and the trashing of a hotel room in time-honoured rock star fashion is bound to come across as either juvenile, attention-seeking, or both. It may of course be the accidental result of over-ferocious partying, but it is perhaps more wilful than that, and not simply for publicity purposes.[11]

Kennedy will apply the phrase ‘do some damage’ both to partying and to playing a classical concerto. What matters, it would seem, is that the experience is intense, even ‘dangerous’, with nothing treated as sacrosanct.[12] And this points to another similarity, at least in Kennedy’s view, between music and football (and indeed partying)—where the ‘result’ is unpredictable. For Kennedy, improvisation is at the heart of all music. As Hamilton states: ‘With a pop star or an opera singer, when you turn up for a performance, you usually get more or less what you go to see, or hear’ (ibid.:14), and for Kennedy that is an anathema. He mentions the ‘subtle and pervasive influence of a special kind of ritualism, one that inappropriately transforms many of our musical performances into liturgical services and that encourages our audiences to respond to them accordingly’ (1991: 116); ‘audiences tend to regard a composition as a received text. The performance is taken by the cognoscenti, not as a lived experience, but as the reverent reading of a sacred writing’ (ibid.:116). The implications of this are pronounced in the direst terms: ‘If you do the same thing every night, that’s the death of music’ (in Culshaw 2010: n.pag.).

Is there, then, an irony that Kennedy has performed one piece, Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, so very many times? Such ‘repetition’ might be considered a risk, in terms of something remaining fresh, but for Kennedy (who in any case thrives on risk), the multiple renditions of Vivaldi are charged with his belief that each performance is a unique event. As Eric Cantona said, of playing at Montpellier FC: ‘Our mission was to interpret The Magic Flute, every Saturday’ (in Hind 2009: n.pag.).

Conclusion

In Hamilton’s poetic text, Gazza Italia, there is a fascinating exchange when Hamilton and Gascoigne actually meet:

‘Have you ever played football?’ asked Gascoigne.

‘Well, no, not really, not ...’

‘Well, fucking shut up then.’ (Hamilton 1993: 102)

I feel at risk of a similar put-down. I play the violin (and football), but I’m a poor amateur, in awe of the artistry of Nigel Kennedy or Paul Gascoigne. Why am I so presumptuous in thinking I have anything to ‘add’ to what such artists accomplish? I don’t want to be a commentator (though there’s an artistry to that, in the case of a Barry Davies or John Motson); I am more interested in being an interpretive narrator—like Kennedy in his ‘recreation’ of England v Poland. And since my own best skill is with poetry, there will be poems in my Kennedy book.[13]

On 30 May 2011, in the foyer of the Royal Festival Hall, even those of us familiar with Nigel Kennedy’s work—and indeed the level of unpredictability that goes with it—had any real idea what we were going to see or hear. Nor can we easily ‘revisit’ it: almost no record exists of the entire, extraordinary weekend—apart from a few illegal recordings by members of the audience (despite the vigilance of Jude Kelly and others)—and nothing at all of the World Cup Project itself. I seem to remember official cameras, but presumably the ‘result’ was not deemed acceptable for distribution. I doubt that Kennedy would have been worried about that. He believes, as do many other artists and performers, that a privilege belongs to those who attend—those who have paid money, travelled—and in the importance of the ‘moment’.[14]

There were moments of brilliance. Towards the end, a snippet of the British National Anthem emerged, just as it might from the crowd. And the fact that the assembly moved into the adjacent ‘late room’, as if to a pub near Wembley after the match, to celebrate or commiserate, but also to enjoy more music, fuelled the sense of an event that had proved momentous—both historically and in its recreation.

Reviews were not altogether enthusiastic. John Walters, writing in The Guardian commented:

Kennedy’s riffs were redolent of Hot Rats-era Zappa, electric Miles and white funk. There’s nothing like Wembley and endless feedback solos to bring out one’s inner bloke. The match was better structured than the music, though, as heroic goalkeeper Jan Tomaszewski made save after save against the vivid green pitch and K-tel ads of 1970s TV football. When Poland scored, the audience erupted, but the ‘soundtrack’ just riffed on until coming to an arbitrary halt. Combining football and music is a great idea, but it may need a more responsive lineup. (Walters 2010: n.pag.)

Nevertheless, the same reviewer said, of Kennedy’s earlier performance that same day, with the Polish klezmer band, Kroke: ‘He plays like an angel, pushing the terrific band’s quasi-classical tone poems, rapturous rhythms and heart-tugging folk melodies to another level’ (ibid.).

Kennedy is a performer who never gives less than total commitment—to his vision, his audience, or the moment—whatever the communal relevance or the aesthetic of that moment might be. Nor is he content for music to deliver what an audience is accustomed to. Even if the audience consists of ‘fans’, his instinct is to confound their expectations.

Six years after the Polish Weekend, Kennedy provided the opening entertainment[15] at the 2017 Australian Open men’s final between Roger Federer and Rafael Nada, highly appropriately, I thought, with a piece called ‘Face-off’, a hard-hitting electrified number deriving from Vivaldi’s ‘Summer’. Some of the online reaction, however, was appalled. Just when his shock value might perhaps have worn off, there was Kennedy offending not the classical music establishment, as he did of old, but a differently conservative audience whose taste is middle-of-the-road bland pop. But bland, surely, never won a match, or nobly failed, while Federer, Nadal, Channon, Tomaszewski, Gascoigne and Kennedy have all thrown heart, soul, body and mind into the fray to make the world a richer place.

[1]. One participant in the symposium, with Polish heritage, recalls the excruciatingly dismissive ITV comments about the Polish team. Poland eventually finished third in the whole tournament.

[2]. Clough’s own dramatic story is the subject of The Damned Utd, a book by David Peace (2006), adapted for the screen by Peter Morgan as The Damned United (2009).

[3]. Years later, when Tomaszewski met up with Brian Clough, Clough retracted his ‘clown’ comment. He said he was absolutely wrong, which must have been an all-time first.

[4]. Kennedy himself puts little store in anniversaries: 'They celebrate the two most worthless days of a composer’s life, which is his birth when he’s just a screaming baby, and when they die, and they celebrate that as well, even though they never write anything beyond the day they die' (in Roddy, 2010: n.pag.).

[5]. Even then, Kennedy rarely wore anything resembling traditional attire.

[6]. The ‘Hillsborough disaster’ occurred during the FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest at the Hillsborough stadium in Sheffield, 1989. 96 people were killed and 766 more injured as a result of overcrowding. Controversy about responsibility for the disaster continues to this day.

[7]. There is similar word play in the album Kennedy's Greatest Hits, the back cover of which features him wielding a violin like a cricket bat.

[8]. Bewilderingly, Kennedy also talks a lot about boxing, and referring to his EMI days he talks of 'people in his corner'. That sort of imagery was taken up by the press when he came out of his so-called retirement from the classical circuit. One pictorial carried the text: 'Great sporting comebacks: Nigel Kennedy is back in the classical ring. But will it be a case of Muhammad Ali – or Mike Tyson?'

[9]. There are notable exceptions: Kennedy has formed close, mutually respectful bonds with conductors including Vernon Hadley, Klaus Tennstedt and Leonard Slatkin.

[10]. At the more banal end of the spectrum, a site called ‘Swapping Shirts with Shakespeare’ has over 16,000 poems posted (accessed 11 September 2018).

[11]. When, in 1992, the Sunday Mirror carried a story of mayhem in Berlin, Kennedy’s spokeswoman replied: ‘He is grateful to [you] for giving him a lot of publicity in your newspaper at a time when he is releasing a new album’ (accessed 11 September 2018).

[12]. Self-damage and damage to his own property is part of the picture. With Gary Lineker, Kennedy invented Kitchen Golf:

This involves whacking a golf ball around the kitchen, seeing how much damage you can do to plates and dishes. Lineker used a nine iron so he had a decent amount of gradient. With one swing he destroyed half the crockery in the house and took three windows out. Very impressive.

[13]. These include new translations of ‘The Four Seasons’ sonnets that appear in Vivaldi’s score. See Munden, P and A Zummo 2018, ‘The Four Seasons in Flux: Interpreting Nigel Kennedy through a hybrid biography’, TEXT Special Issue 51, ‘Climates of Change’ (accessed 15 April 2019).

[14]. Simon Armitage made such a comment when the organisers of Poetry on the Move 2016, in Canberra, asked if video recordings of his presentations might be made.

[15]. Kennedy had done something similar in 2009, giving a special performance with his jazz quintet to mark the conclusion of the World Athletics Championships in Berlin.

Allison, J 2007 ‘Kennedy’s in Pole Position’, Gramophone (November), 85 (1025)

Bates, HE 1952 ‘Brains in the feet’, The Sunday Times, 16 November

Bevan, C 2013 ‘England v Poland 1973: When Clough’s “clown” stopped England’, BBC Sport (14 October), https://www.bbc.com/sport/football/24445822 (accessed 11 September 2018)

Brown, M 2010 ‘Nigel Kennedy lines up soundtrack to 1973 England v Poland game’, The Guardian (9 March), https://www.theguardian.com/music/2010/mar/08/kennedy-improvisation-poland (accessed 11 September 2018)

Culshaw, P 2010 ‘Nigel Kennedy interview for Poland Weekend’, The Telegraph (26 May),

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/classicalmusic/7767278/Nigel-Kennedy-interview-for-Poland-Weekend.html (accessed 11 September 2018)

Doan, D 2017 ‘All great soccer players are poets’, The Poetry Foundation (24 October),

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet/2017/10/all-great-soccer-players-are-poets

(accessed 11 September 2018)

Hamilton, I 1993 Gazza Agonistes, London: Granta

Hamilton, I 1994 Gazza Italia, London: Granta

Hind, J 2009 ‘Did I say that?’, The Guardian (3 May),

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2009/may/03/eric-cantona-football

(accessed 11 September 2018)

Kennedy, N (n.d.) Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/pg/nigelkennedyofficial/about/ (accessed 11 September 2018)

Kennedy, N 1991 Always Playing, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson

Kennedy, N 1996 Kafka, CD, EMI

Kennedy, N 2010 SHHH! CD, EMI

Kennedy, N 2011 Nigel Kennedy's Polish Weekend programme, London: Southbank Centre

Kennedy, N 2017a Nigel Kennedy Australian Tour programme, Paddington, NSW: Playbill

Kennedy, N 2017b ‘Nigel Kennedy talks about his devotion to Aston Villa F.C. ’, The Strad (21 September), https://www.thestrad.com/video/nigel-kennedy-talks-about-his-devotion-to-aston-villa-fc/7140.article (accessed 15 April 2019)

Kennedy, N 2018 Kennedy Meets Gershwin, CD, Warner Classics

Larkin, P 1971 The Whitsun Weddings (2nd edn) London: Faber and Faber

Munden, P and A Zummo 2018, The Four Seasons in Flux: Interpreting Nigel Kennedy through a hybrid biography, TEXT Special Issue 51, ‘Climates of Change’,

http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue51/Munden&Zummo.pdf (accessed 15 April 2019)

Pelé (with Robert L Fish) 1977 My Life and the Beautiful Game: The Autobiography of Pelé, New York: Doubleday

Roddy, M 2010 ‘Violin’s “bad boy” Kennedy brings Poland to London’, Reuters (12 May),

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-music-kennedy/violins-bad-boy-kennedy-brings-poland-to-london-idUSTRE64B2BF20100512 (accessed 11 September 2018)

Sweeting, A 2010 ‘Nigel Kennedy’s Polish Adventure’, theartsdesk (14 June).

https://theartsdesk.com/classical-music/nigel-kennedys-polish-adventure (accessed 11 September 2018)

Wallace, H 2000 ‘They're only making plans for Nigel’, BBC Music Magazine (March)

Walters, J 2010 ‘Kroke/Nigel Kennedy’s Polish Weekend’, The Guardian (2 June),

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2010/jun/01/kroke-nigel-kennedy-polish-weekend-revie (accessed 11 September 2018)