Reality Perching

In mid-August 2016, I found myself standing on a chair in my studio with a helmet-like headset strapped to my face, reaching up into the air with a plastic Virtual Reality (VR) controller in either hand. I had no way of viewing the so-called ‘real world’, and had no visual reference points to guide or orient me while in the mad creative throes of crafting a ‘sketchsculpt’ (not exactly a term that rolls right off the tongue), a type of cross between a sculpture and a sketch, one that at present can only be created via a set of Virtual Reality tools.

[Perched with one leg balanced on a chair.

Charcoal-dense Virtual Reality headset = face-[s]trapped.

Mitts reaching up

into

beyond]

…this experience was unique, and typifies precisely what it’s like to create in a Virtual Reality space.

Exi[s]t Here

It’s almost like multiple-choice…

a) Existence: here?

b) Exit-the-real-world + swoon?

c) Resist-the-known + contemplate-drool?

Or d) ALL OF THE ABOVE.

[ie Yes pls: 2d) ].

…how, then, does the entire sketchsculpt creation process work in terms of a user being ‘reality blind’ and positioned in a physical space and a virtual space simultaneously?

The SketchSc[G]ulpt

How exactly does a VR user create one of these sketchsculpts without walking into a wall, stubbing their toe, or worse? The answer lies in the system construction that ensures a user in the physical space doesn’t attempt to venture beyond the physical area in which they are located through the creation of a visual reference system of chaperone boundaries. These boundaries are activated as a set, or grid, of visual lines that pop up in the VR space when needed, and that mimic the dimensions of the physical space in which a user is positioned. This system is termed Roomscale VR, and involves a user moving in the VR space through positional tracking (using a simulated movement system called ‘teleporting’ in order to relocate to different simulated areas) while being restricted in physical space for their own safety. Roomscale VR allows a user to physically move and walk in a finite mapped space that is specifically designed for intricate VR crafting.

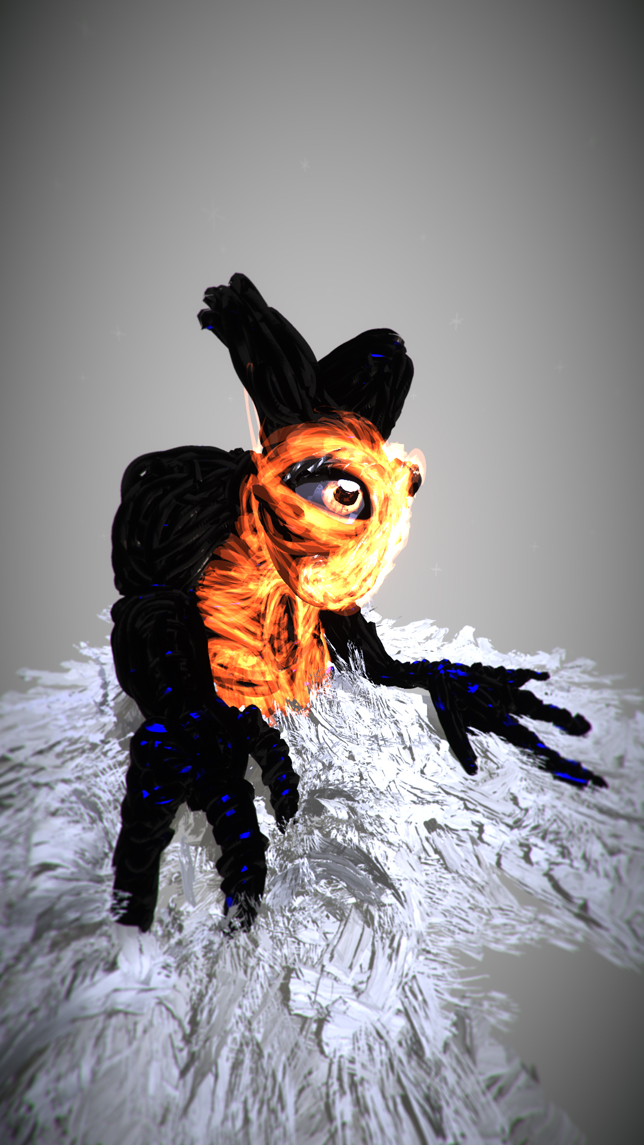

Figure 3: A shot from below of the virtual-monster-snoz-+-maw.

Representational Shard-[f]Licks

Jumping back…

…to the

Not-very-safety-conscious perching image

In my studio

Blind + reaching + thinking:

‘Oh my gawd this could really go belly-up here, if I move my foot just a bit too far over the chair seat edge while getting this brush stroke *just* *right* I’m toast, but omg it WILL LOOK SO AMAZINGLY GOBSTONKINGLY GOOD IF I GET IT JUST RIGHT!!!!’

…which prompts the ask: why am I keen to continue working to create in a VR space that not only endorses questionable Occupational Health and Safety practices, but which is also expensive, somewhat difficult to use, and creates conditions that make it impossible to robustly interface with the physical world at any workable level?

In short: it’s wondrous.

That feeling of first putting on a VR headset and seeing the physical world completely rewritten by an intricately immersive simulation is incredible.

And I’m no novice when it comes to working or playing in 3D augmented environments. I’ve been a gamer since my teens, madly playing first-person shooters Doom and Quake in the mid 1990s, and back in the day dabbling in VRML environments (similar to 360 videos and photos of today).

I’ve reached incredible immersion peaks within Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games such as Everquest and World of Warcraft. I’ve co-created a video game designed for Augmented Reality headsets in 2013 called #PRISOM, and created a theory-based publication from 2008 to 2010 about all things augmented and synthetic called ‘Augmentology 101’.

In essence, I’m not exactly new to the concept of picking up ground-breaking tech and using it in surprising and unconventional ways.

So why, when popping on the Vive headset and booting up VR software for the very first time, did I find it all so powerful? So amazing? It all boils down to successful immersion. Being able to see the hand gestures I was making with the controllers in the real world mirrored precisely in the virtual environment was at first discombobulating: then, on realising the controllers I was physically holding were being both replicated and tracked perfectly in the VR space, I was hooked.

Awaiting the Reach

Was the sketchsculpt completed?

Yep.

Did a perch-fall occur where body-bone-breakage resulted?

Nope.

Was the resultant sketchsculpt:

Perfect? = No.

Will it engage and delight viewers till the end of conceivable time? = No.

***BUT***

The resulting VR sketchsculpt is/was *palatable*

+ *Interesting*

+ Ultimately needs more work.

***AND***

The stroke-promise of VR has….reach, and potential.

Just how far, then, can this reality-perch-reach take us?

Who would benefit from using this VR tech specifically?

…it’s a fantastic tool for sculptors, illustrators, and graphic designers, with possibilities of creating new works that can be imported into programs like Sketchfab and then manipulated further and/or 3D printed. There are possibilities for the use of such programs in education, with teaching instructions, sets being rigged up to VR programs where a user pops on a headset and replays exactly the steps required to fix a vehicle, or disassemble a mechanical part, and reassemble it.

There’s also potential use in the fields of choreography and fashion design. Having the ability to save multiple versions of each sketchsculpt at various stages of development and then rework them directly from any of these stages is remarkable. So, too, is erasing, editing, and the ease of redoing various sketchsculpt elements even for the value associated with creating originals (which the art of digital remixing has already muddied).

When VR tech becomes untethered, less dependent on high-end computers and more mobile-oriented, then mainstream adoption of VR devices becomes more likely (and affordable). Using such VR programs to create works that can’t easily be monetised or codified in a socioeconomic system designed specifically to sell works based on their originality/standalone value is also an interesting dilemma for creatives.

Another issue to do with using VR software to create works is: if I turn off the hardware and the artwork disappears, is the artwork still ‘real’? How does this stack up against ephemeral performance art, other digital-based creations, or one-off festivals/events, or stage plays, or ebooks?

With a play or a music festival or performance you can record the work, but can you then easily alter a fundamental aspect or property of it: scale it, or erase and rework it, all with one simple action?

Questions such as these go to the heart of using such new VR technology and just how it’s to be incorporated into creative industries and arts practice. For now, I hope you, like me, will be content with playing with the potentials of such deliciously open VR technology, just to see how far our reach can take us…

*…looks directly at = thru u.*

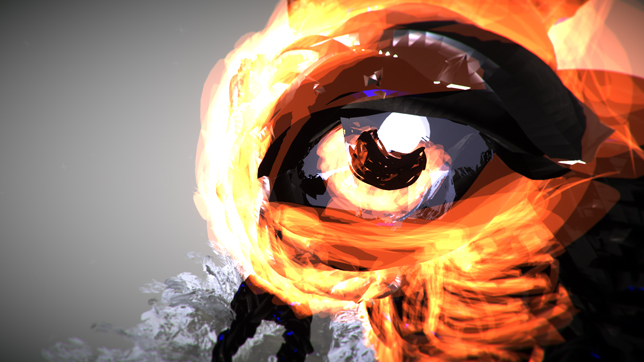

Figure 5: His pregnant-pause-gaze, directed at-&-thru u, awaiting ur reach, ur perch-moment.