Singapore poetry in English tends to be read as a lens through which the nation is made and remade. While not unfruitful, such approaches tend to focus on history as a series of events happening over time, ignoring the fact that poetic form, like other categories of art, also has histories worth unpacking. Concomitant with this is the fact that such poetry is overwhelmingly written in free verse, more a de-facto stance than a reaction against form.

In my examination of two contemporary poets, Joshua Ip and Koh Jee Leong, I focus on their contextually unusual commitment to metrical forms: both their debuts are collections of sonnets. I investigate what it is they say through form, and how they are negotiating multiple, perhaps false dichotomies—East/West, state/self, high art/pop culture, reader/speaker—and invoking form while subverting content enfleshes that balancing act.

Keywords: Sonnet – Form – Poetry – Postcolonial – Anglophone – Singapore

The English sonnet is a political problem. Jeff Hilson, in his introduction to The Reality Street Book of Sonnets—an anthology of ‘stretched, deconstructed and re-composed’ sonnets—frames the issue around form (2008). On one side: sonneteers who keep to form and the mainstream publishers who anthologise them, reacting against linguistic innovation. On the other: those who refigure the sonnet, reflecting contemporary tastes. The stakes are hyperbolically high:

Just as its varied structural features ... can’t be disturbed without destroying its integrity, so the sonnet itself stands as a metonym for the kind of poetry published by the big publishing houses. To disturb the sonnet’s form too radically therefore is ... to endanger the foundations of the wider poetic tradition. (10)

If by wider poetic tradition Hilson means ‘Western’, he might be right. However, this dichotomy of tradition/innovation in form dissolves when reading postcolonial sonnets. The poets in Hilson’s anthology all come from the UK and its settler colonies, implying that postcolonial sonnets are formally conservative. Yet, I cannot find many in mainstream anthologies either. If the sonnet is a metonym for traditional poetry, then any postcolonial sonnet is no sonnet at all—precisely the type of sonnet that should be examined. Preserving structural features such as meter, rhyme, and volta, but largely absent from publications dedicated to showcasing the form in English, they are, following Homi Bhabha, ‘Almost the same but not white’ (2001: 384). The political problem grows.

I look at two contemporary books of sonnets by Singaporeans, the only published examples to my knowledge[1]: Payday Loans by Jee Leong Koh (2007, reprint 2014), an émigré to New York, and Sonnets from the Singlish by Joshua Ip (2012), a public servant. Both books preserve form, and may be thus called traditional, but a closer look reveals innovative engagements with Singapore’s culture. If the sonnet engenders creativity through formal constraint, Singapore might also have blessed Koh’s and Ip’s poems with its own peculiar limitations. First, recognising that the audience for poetry here is tiny (but growing) results in poetic personae being unusually aware of themselves as speakers communicating with readers. These speakers then attempt to win these imagined readers over by employing various rhetorical strategies. Second, the lack of time to write amidst pervasive and growing demands of remunerative work manifests in self-conscious uses of the sonnet and sequence as a means of ordering time. Both books were produced by writing a sonnet a day for a month, demonstrating how the forces of capitalistic productivity might be harnessed for artistic ends.

Without discussing the history of the form in depth, it is worth noting that the sonnet’s spread has always crossed culture and language, from Italian to other European tongues, from Britain to its empire. What makes the sonnet in English postcolonial does not depend simply on contextual translation, but also on its emergence as a valuable form through colonial education. In British India, Thomas Babington Macaulay argued for diverting money from Sanskrit and Persian to English-language publications and teaching:

Whether we look at the intrinsic value of our literature, or at the particular situation of [India], we shall see the strongest reason to think that, of all foreign tongues, the English tongue is that which would be the most useful to our native subjects. (1835)

English literature in Singapore and the rest of the empire was funded so the natives might recognise Britain’s inherent superiority. Interestingly, in Macaulay’s time, Shakespeare and his modified sonnets were reevaluated by scholars and poets as examples of great writing in general (Sanderlin 1939: 464).

Marya Grant suggests that poets in Italy, Britain, and India first began writing sonnets to increase their status during a period of national formation and development; the sonnet’s traditional theme of desire for a beloved doubled as a desire for political favor (2008: 2). Post-independence, Indian sonneteers became more formally experimental, investigating ‘notions of history, heritage, culture, and self to fit with contemporary global concerns’(43). This shift from formal conservatism to experiment prefigures Hilson’s anthology, again implying a distinction between the traditional sonnet embodying ‘Western’ power and values, and the deconstructed one questioning both. The nascent Singaporean sonnet tradition, however, emerges in the 2000s, when Singapore’s independence and decolonisation is well- and possibly over-established.

In the Singaporean postcolonial sonnet, therefore, innovation does not equal formal disruption, and traditional form signifies tradition’s destabilisation. Instead of framing the sonnet as a status symbol to a political elite, Koh and Ip appeal to the middle-class, mass-educated reader of English who is not necessarily conversant in literary history or theory, but who has some idea of sonnet structure. The sonnet becomes simply a short, humorous, melodious form that accommodates readers of varying levels of poetic literacy, while remaining familiar from the fallout of Shakespeare’s continuing but diminished presence in English Literature classrooms. Adhering to traditional structure is no longer primarily an issue of canonicity but instead evokes a sense of novelty in a milieu where free verse dominates poetic production. The postcolonial sonnet here, its history no longer a defining factor, can represent culturally specific, everyday issues in a near-universal form while also questioning the assumptions undergirding this universality.

At this moment I would like to sketch why a perceived lack of and a corresponding desire for mass readership should imprint itself so strongly on our Anglophone poetry. The introduction to Writing Singapore claims English-language literature is burgeoning:

In the last forty years, a secondary consequence of government policies that established English as the medium of instruction in all schools has seen a growth in writing in English and indeed an audience for such writing. (Poon, Holden, and Lim 2009: xxi)

Singapore has exchanged colonial education’s fixation on Britain’s inherent goodness with a pragmatic, neocolonial promotion of English as a bridge between cultures and to the wider world. Unsurprisingly, the National Literary Reading and Writing Survey 2015 discovered that while 91% of readers read in English, only 44% of respondents had read a literary book within the past 12 months; of these, 4.5% read poetry (National Arts Council 2015). Readers of Singapore poetry, while not measured specifically, are doubtless fewer. Considering the absolute size of Singapore’s population and the fact that the reading public has been growing, English-language poets write to a miniscule audience. Instead of embracing the elitism of the medium, most Singapore writers and literary activists support efforts to encourage more people to read Singapore poetry, although it is not yet clear why. Koh and Ip are behind Singapore Unbound and Sing Lit Station respectively[2], two organisations that promote Singapore writing, including poetry, to a local and global audience.

To that end, Koh and Ip’s poetic personae speak as everymen even as they do so in sonnets. Their speakers address those interested in Singapore poetry (and who are also presumably more familiar with the ‘Western’ canon) and the rest of the English-speaking world, even though both groups are privileged by their proficiency in this global, elite language. Koh and Ip develop interrelated but distinct voicing strategies to convince this ‘general’ audience of poetry’s worth. Ip’s, I’ll argue, is akin to seduction, while Koh’s is confrontation. Both strategies emerge from the sonnet’s history as a status symbol, where status is no longer measured by political approval, but instead by mass readership, one seemingly unattainable in poetry writing.

Ip builds a distinctly contemporary Singapore seen slant through the formalism of his verse. This move sometimes dramatises the gap between poet and public. In ‘k ge zhi wang[3] attends a poetry reading’, the Karaoke King finds fault with poetry’s drive to make it new: ‘in karaoke, in his element,/ originals are shunned’ (23). ‘[R]ead me familiar stories, stanzas, quotes’, implores the King, and yet the poem satirises this attitude. The presence of ‘k gods’ and ‘captive audiences’ to whom respect is due reveal the King’s blind allegiance to nostalgia and artistic conservatism. He stands for the public who cannot or will not be challenged, preferring factual reports and clichés to original verse.

The first move Ip makes, then, is to tease the reader out of this comfort zone. I look closely at ‘entry’, his first sonnet; it demonstrates both his strategy of winning over the reader, and the collection’s humour and interpretive possibility. The poem describes itself as a recruit, while readers are military inspectors. It has ‘surrendered its identity’,[4] offered itself up to literal change—‘i’m willing to refine it’. However, the poem subverts its seeming submission. Its unruly meter is hardly ‘clean-shaved’, its ostentatious internal rhyme far from ‘[solemn] declar[ation]’, protestations of transparency finally undercut by its humour. Readers begin to recognise the poem as a discourse of seduction, Ip’s primary strategy of pleasure. Writing and signing the poem in a ‘book-in book[5]’, readers allow it access to the highly controlled army camp of their minds.

In ‘entry’, infelicities in discourse shape reader-speaker relations. The first stanza uses labels to reassure and confuse readers, alluding to its ‘intentions and directions’ without naming them. The deitic function of the label goes unfulfilled; what it points to too vague to be meaningful. The poem performs and parodies any discourse claiming to be clear while harbouring complex or contradictory intentions and directions. The same could be said of most of the other statements in the first stanza.

In the second, the poem continues to play recruit. Declaring ‘it does not keep/ in its possession any media’, the language parallels the oath of soldiers who cannot possess rounds after live firing exercises. Yet poetry is mediated meaning—the poem cannot take its oath truthfully without denying its existence. That the poem ‘is free/ of any image-capturing device’ again both echoes the camera ban in army camps and shows the impossibility of excluding images and imagery from poetry. These paradoxes show that the relationship between text and reader is nothing like that of recruit and state. The state may discipline its army, but a poem by definition resists any vacation of meaning or critical closure.

By the third stanza, the reader knows not to take the poem at face value. The focus is on good form: the poem presents itself ‘tucked-in, clean-shaved, and iron-creased’, every stray thread (‘cock-hair’) removed. As a sonnet, however, it wears its uniform slant: the meter varies from 5 to 7 beats a line, takes frequent excursions out of the iamb, uses half rhymes like ‘last’/‘dust’, and insists on lower case a la e.e. cummings. Of course, poetic form is not uniform; ‘rules’ in verse are modified almost as a rule. A poem ‘so shiny you can see your face inside’[6] suggests technical polish revealing, finally, the reader’s own image. Ip chooses the extended army metaphor to surface the fundamental incommensurability of poetic and military power. Where the latter can coerce, the former can only persuade.

In the final couplet text and reader relations are complicated and clarified by the speaker’s appearance. Readers have been led to assume that speaker is poem, an independent consciousness. Now, the ‘I’, separate from poem, reveals itself as the poet (‘i’m willing to refine it’). Unable to get the poem approved through force or self-contradictory obsequiousness, poet pleads with reader. No more need for the text to erase its distinctiveness: written down, autographed, it assumes a marked and material presence in its mediated, imagistic, metrically disobedient glory.

If sonnets are typically love poems, this one seduces. It gains acceptance by pretending to be transparent—‘your will be done’. When this is shown to be both impossible and a ruse, the poet steps in, desirous to work with the reader to revise the poem. Again, the poem having already been printed, this too is impossible; the poet finally admits the reader must ‘take it or leave it’. Every line, even and especially the impossible or self-contradictory ones, points to an overwhelming need for poetry to be validated and accepted.

The poem is also a gift that binds the recipient. Its title, ‘entry’, refers both to entry in the book-in book and the poem-soldier’s entry into the reader’s mind-camp. The reader owns the book-in book, may accept or reject the poem. Insofar as the reader’s mind is an army camp, we can assume that speaker sees reader as discriminating, wary of letting in unwanted, unverified personnel for fear of security breaches. Poems are not passive; once in camp, they sneak around, interacting with other agents. In accepting the poem, the reader also bears responsibility for consequences that arise.

It comes as no surprise that Ip compares state with poetic power, investigating the correspondences but also the limits of such comparison. As a public servant and a poet, Ip embodies this tension between pragmatism and aestheticism, coercive and persuasive force. His arguments for poetry, that which exceeds purely communicative concerns, are disguised as pragmatism. Ip’s work succeeds in maintaining an illusion of accessibility to the general public precisely because of this. Writing about everyday issues (‘the shitty carparking in orchard road’, for example) in sonnets, he demonstrates the seductive power of poetry to give pleasure, while claiming that such pedestrian themes are fit to be verse.

Koh’s poetic strategy of pleasure is also inflected by his relationship to the Singaporean public. A former evangelical Christian teaching at a public school, he moved to New York, coming out as gay and a poet both (65-6). For him writing poetry is inextricable from homosexuality. He exchanges Singapore for a new geographical, vocational and sexual landscape—pragmatism for pleasure. This conversion narrative, however, is problematic. In Loans are speakers debating with the past, the pragmatist, the straight man—symbols contrary to Koh’s newfound identities. ‘Gay’ and ‘poet’ cannot fully represent Koh and his concerns. His strategy of pleasure confronts both his speakers’ inconsistencies and an imagined reader embodying the largely conservative socio-political structures Koh left behind.

In ‘April 14, Thursday’, the speaker compares his former life to a ‘low fever’ brought about by church and state, announcing that in this new one ‘Poetry is my chosen course, the lever/ for straightening dislocations in my bed’ (27). Poetry is a course of action and a course of medication. Yet the ‘you’ is critical: ‘You read my work for indiscretions, claim/ them yours, to be used only with permission’. The reader inserts their own intentions and injunctions, limiting the speaker’s supposed freedom. Crucially, ‘you’ personifies both constraint and love—‘Love, are you Priest or Law, another name/ for Censor?’ The speaker recognises a love motivating the restrictions of church and state, and a love for both, re-coding the fever of youth as passion: ‘Or is my love in remission?’ He confesses his ambivalence to Singapore, a Singapore in which state, church, and public are imaginatively blurred.

In ‘April 13, Wednesday’, confrontation extends beyond poem into real life. A John Donne-esque carpe diem love poem, it announces: ‘Come on, straight boy, and make gay love with me’ (25). As the straight boy gets an unwanted advance, the authorities banned the poem’s performance at a local gay pride reading (75). In light of difficulties facing the reception of both poetry and homosexuality in Singapore, the appeal for sex is an appeal to be read, another conflation of orientation, vocation, and freedom. Making love with women constrains—‘Why, in an oven she loves regulating,/ you stick in your tray of cookie dough, and wait?’ (25). With men, however, there is pleasure—’they know well how to give/ each other head’.

Koh advocates poetry as art for art’s sake, sex for sex’s sake. However, the speaker appeals to pragmatism in the form of farcical insistence on the inconsequentiality of gay sex. ‘One night of loving will not turn you queer’, the gay man assures the straight boy: ‘What have you got to lose? Leap, acrobat!/ You can always fall back on pussycat’. As in ‘entry’, the sceptic is addressed. However, where Ip’s speaker warns of poetry’s transformative power, Koh’s speaker downplays the importance of sex acts on one’s identity, by extension downplaying the effect of reading poetry on one’s worldview.

Clearly, Koh does not believe this. His speaker has strong desires but weak justifications for them. The speaker wants instant gratification—woman’s oven needs waiting for, man gives ‘straightforward relief’. Pleasure is good because it is inconsequential and immediate, yet poetry is rarely instant; desiring quick, painless fun is precisely the stand of a pragmatist. Using poetry to praise the instant is contradictory. The confrontation with the straight man and regulatory authority only exists on the page. Readers realise that these forceful displays of rhetoric are knowingly impotent. ‘The ban’ on the poem, the book’s author page declares, ‘made Koh Jee Leong out to be more dangerous than he is’ (75).

In ‘April 16, Saturday’, conflict between poet’s and reader’s desires again leaves the poet helpless. ‘You’, both lover and reader, searches for the speaker’s old poems, enjoying one ‘in a style so jeweled/ I blushed and stripped it down to a bright nude’ (31). The beloved loves ‘the body shod and gloved’, loves intricate writing; Proust is mentioned. Yet this reader knows little of the power of words; he derives pleasure more from superficial attraction to the overwrought than from any real engagement—’vaguely, vastly, you were moved’. In contrast, the speaker desires plain honesty, ‘bright nude’ style, bare emotion.

At a poetry reading, the speaker ‘strip[s] before a cheering crowd’, baring his soul to an audience while desiring acceptance only from his beloved. Heartbreakingly, the beloved replies with ‘faint praise’, disliking the new style. Yet Koh does not intend to confuse his speaker’s early style with Proust’s—rather, he suggests that the reader/beloved cannot distinguish lushness from pretension. Conversely, the confessional is not necessarily an indicator of good writing. There is ‘pulchritude/ [in] blurry windows’, beauty in veiling things that cannot be fully exposed. The reader’s love for the speaker’s older poems and Proust stems from a beauty he senses but cannot fully articulate.

This explains why the speaker craves the reader’s acceptance; although perhaps naïve, he intuitively discerns beauty. Although the speaker gains a larger audience, he has lost the one reader he cares for, and his evolving aesthetic is responsible. Without going so far as to claim that this particular reader/beloved represents a Singaporean audience, I suggest the speaker is torn between past and present. His lover senses something deeper about his early work (‘you saw more than I did’), and now he runs a crowd-pleasing stripper act. The final image of glass brings to mind a mirror cracking in the face of the speaker striving for naked honesty but ending up with barefaced dishonesty.

In these three poems, Koh’s strategy of pleasure surfaces through ambivalence underlying every confrontation between speaker and reader. Each works through the love-hate relationship between ‘I’ and ‘you’. Every criticism of Singapore is enriched by the affection the speaker still feels towards it, every brash assertion of homosexuality or a new, naked, style of writing undercut by doubt over the subject’s ability to effect change, and mourning what was lost on the path of change. Insofar as these poems end without resolution or with an admission of impotence, Koh, like Ip, realises that poetry cannot force engagement. Surfacing these conflicts on the page is vulnerability, a way through which Koh shows he wants his beloveds—whomever they may be—to reciprocate his love despite every disagreement.

Ip’s and Koh’s speakers know their voices may not be heard or accepted. While Ip’s charm themselves into readers’ minds, Koh’s argue with them in a way that admits desire. Both strategies are a result of a shift in attitudes towards poetry after empire, where power appears to reside in the average person, in appeals to democracy, even as poetry remains a niche production. The paradox of tiny actual audience versus desired mass readership, of elite poets and readers versus an aversion to elitism, reflects a bigger problem of whether Singapore writing should aim for a local or a global readership. Knowing that the local audience is limited rubs up against the desire to speak to local culture rather than merely write to the ‘West’, driving these poems to cater to both groups at once. The success of Koh’s and Ip‘s poetry, therefore, depends on whether they succumb to this dilemma or productively stand in the gap not just between high and low art but between ‘East’ and ‘West’.

Although pragmatism and pleasure have been placed in opposition thus far, it is through ‘productivity’ alluded to above that poetry can attract a Singaporean public largely concerned with results, performance, growth. Productivity is applied to composition methods; both Sonnets and Loans were birthed from attempts to write a poem a day for a month. This self-enforced union of poetic pleasure and pragmatic effort creates a better poet. Ip writes, in his preface to the second edition of Loans:

A constraint, like the onerous sonnet form, like the twenty-four hours Jee Leong set himself to complete each poem, seems an unnecessary set of weights for a young poet to carry. But there are three benefits of constrained writing that surface upon closer examination—discipline, focus, and challenge. (xvii)

The sonnet form stands as a symbol of creative constraint; the poet grows by self-imposing metrical and temporal limits.

This method is not unique to Ip or Koh, or indeed Singaporean poets. In April 2003, Maureen Thorson announced the first-ever National Poetry Writing Month (NaPoWriMo). Participants wrote one poem each day, and were encouraged to link up online. Koh wrote most of Loans during NaPoWriMo, on an online poetry workshop (73). Ip posted sonnets on a blog as he wrote them (2012, ‘sonnets from the singlish - origins’). He declared April 2014 Singapore Poetry Writing Month, challenging local writers to write a poem a day on Facebook (‘SingPoWriMo’). SingPoWriMo grows out of and shapes contemporary network culture, both indebted to the global and adapting it. Roland Robertso’s ‘glocalization’ captures this concept: ‘the simultaneity—the co-presence—of both universalizing and particularizing tendencies’ (2001). The sonnet’s recognisable, authoritative form and online composition produces the universalising tendency, while the particularising tendency drives both poets towards cultural specificity and the quotidian.

The production and medium of Ip’s and Koh’s work is an extension of their concern with speaker-reader relations. Following Marshall MacLuhan, it is widely recognised that media are not transparent; form and content cannot be separated except theoretically. In this case, the authors’ productive choices are also part of the message. Online readers watched these collections take shape before their very eyes; these readers could give praise or suggestions instantaneously. They were literally acting out the complex speaker-reader dynamics Ip and Koh embed in their poems. That the first audiences of these poems are online ones reinforces their concealed eliteness—it appears as if any person may now read them, but internet connectivity and familiarity with English are not defining features of most audiences.

Of course, speaker-reader relations are written into the sonnet form as well. The sonnet’s relative brevity, rigidity, and rhetorical structure provide Ip with a template through which thought might easily flow under time constraints:

under the time pressure, every single poem that emerged turned out to be a sonnet. short and somewhat formulaic, the sonnet form was perfect for bashing out thoughts and organising them in a very short germination period. (2012, ‘sonnets from the singlish - origins’)

Ip’s readers also benefit from these characteristics of the sonnet—busy readers, who do not otherwise have time for poetry, can now consume these bite-sized poems on the go. The familiar structure and deployment of the sonnet—in contrast to Hilson’s experiments—serves as a soft landing, assuring readers they need not encounter obscurity or difficulty. The formally conservative sonnet, unburdened from being read primarily as contributing to or desiring colonial power, takes on the role of mediator between poet and reader as a form both easy to write and read.

Working within this framework, Ip imbues his sonnets with languages, cultures, and experiences familiar to modern Singaporeans. More than simply filling ‘Western’ form with ‘Eastern’ content, or ‘old’ with ‘new’, local context structures his poetry. Keeping to form suggests innovation of a different sort, asserting that content transforms how readers conceive of the uses of the form. Treating localness as a fertile source rather than a barrier towards understanding, Ip innovates by writing what he knows. His Singlish sonnets with hybrid DNA speak to both the postcolonial consciousness of Singapore as well as the wider Anglophone world.

‘Chope’ shows how postcolonial glocalisation is mapped onto reader-speaker relations. It means ‘to book, or reserve a place, such as a seat in a fast food restaurant, sometimes by placing a packet of tissue paper on it’ (Ip 2012a: 63). The poem uses this culturally specific expression to comment on increasingly expensive and outrageous wedding proposals—will ‘you’ say yes if ‘i,/ while at a hawker stall, drop to a knee,/ and place a tissue packet on your thigh?’ (2012: 42). Unable and/or unwilling to give ‘you’ ‘flash mobs and fireworks and fighter rides’, the speaker turns away from the materialistic one-upsmanship of the wedding proposal, inviting her to consider ‘the prospect of a hdb’[7]. The abrupt suggestion to ‘chope’ her makes a Singlish term a means of imagining an alternative wedding culture, unspectacular but certainly inventive.

The marriage of the ‘you’ and the ‘I’ occurs in a sweet spot of pragmatism and pleasure—the commitment of buying a house together, the inventiveness of co-opting ‘chope’. This productive proposal also makes use of sonnet form. The octet sets up a problem (too flashy proposals); the sestet solves it by invoking ‘HDB’ and ‘chope’, not as dispensable local colour but as integral elements of the poem’s argument (simple proposals better). Clearly this proposal is also for readers. The persona asks ‘is there an issue of sincerity…?’, and ‘would it be disrespectable if…?’—also questions of a speaker trying to persuade a reader to engage with his work. Lacking either coercive power or capital, the poet chooses the sonnet as a rhetorical device to make a case for his poetry.

‘Rag and Bone’ further illustrates the use of the postcolonial sonnet to relate global and local concerns. The widely understood problem of ecological disaster is laid out in the octet:

we ate and shat, and ate, and shat, and shat

……………………………………………………………………

evolving from our brittle forms

to that which lasts forever—planet styrofoam. (50)

The almost vulgar repetition of ‘ate and shat’ underlies the hysterical cycle of production and consumption. This dystopian vision is the result of pragmatism and pleasure taken to extremes; all natural resources depleted to ‘feed the grow-/ ing appetite of mankind and machines’. Evolution as survival of the fittest becomes, ironically, regression—to survive, man becomes plastic. The sterility of a plastic earth, however, is made fertile again in the sestet.

Two forces contribute to this reinvigoration. First, the karang guni man[8] quite literally makes a living off all the world’s junk; typically of low social standing, he becomes the last man standing, ‘lord of all he sees’. He invests worthless objects with purpose and value, a symbol of productivity. This is the triumph of simple man over worldwide disaster, meaning over meaninglessness, and productivity over either pleasure or pragmatism.

Secondly, Ip incorporates the karang guni man’s distinctive cry—‘“poh chuah gu sar kor pai dian see kee”: hokkien for “newspapers, old clothes, broken televisions”’—into the final couplet (64). He reinterprets worldwide destruction through the lens of a highly specific aspect of Singaporean culture. Again, this is more than a superficial act; Ip’s adaptation[9] of the karang guni call respects the sonnet’s iambic pentameter and rhyme. Just as the sonnet is infused with hokkien, the karang guni cry also changes. Ip takes two traditions and creates something unmistakably related to both, but also different, new, demonstrating the regenerative power of the postcolonial situation.

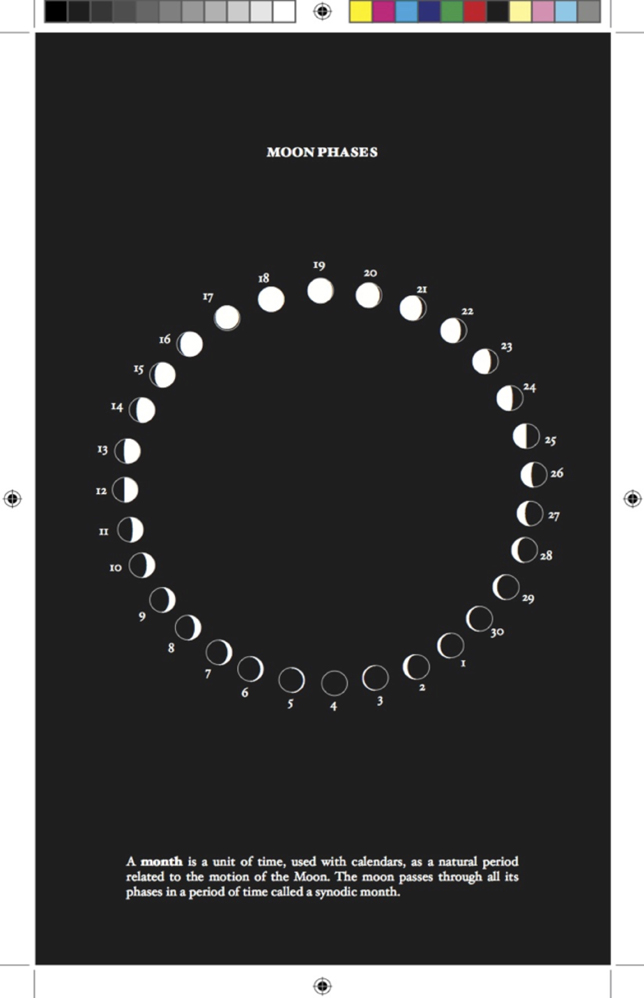

In Koh’s collection, postcoloniality manifests in the use of time. The 30 poems in Loans are, as mentioned, named after April’s 30 days. A draft manuscript of its second edition includes a diagram showing the shape of the moon daily for a month, arranged in a circle (Appendix B). Each poem or ‘day’ is prefaced by another diagram of the moon on that particular day. The text accompanying the diagram states: ‘A month is a unit of time, used with calendars, as a natural period related to the motion of the Moon. The moon passes through all its phases in a period of time called a synodic month’. Although this text was eventually removed, the associations with the Chinese lunar calendar are unmistakable. The sonnet cycle as lunar calendar allows us to compare how time works across cultures.

In ‘April 1, Friday’, the speaker is anxious, uncertain, writing with one eye on the ticking clock, afraid of poverty and potential death. He implores ‘Mr Certain Death’ to lend him thirty—dollars, days, sonnets—promising repayment ‘on my payday / [...] with the surety of breath’ (1). Writing sonnets means living off borrowed time; NaPoWriMo production takes on a sinister, urgent tone in light of this. The speaker ‘[needs] a loan right now’ to sort out the many problems in his life—‘My boyfriend doesn’t want me to move in/ yet. I’m leaving school without a job./ My visa is expiring’. The speaker’s sexual, vocational and geographical freedoms are fragile, tenuous. His response—‘I begin/ again a sonnet when the brain’s a throb’—suggests literary production as a way to stave off this uncertainty, a way of disciplining chaos into the order of the sonnet’s iambic pentameter and rhyme.

The attempt, however, is and must be imperfect. Just as the sestet’s ‘Coke-drinking economist’ finally remarks that ‘it’s irrational/ to borrow from [Mr Certain Death] to subsist’, Koh’s minor deviations from the sonnet form suggest that the speaker’s poems cannot be a perfect substitute for facing up to and living out his future. Adhering too strictly to form is imitation, not art; such an approach cannot appropriately describe the speaker’s state of mind. Koh rhymes ‘economist’ slant with ‘pissed’ and ‘subsist’; the Petrarchan octet’s abbaabba rhyme scheme becomes a more Shakespearean ababcdcd with an unusual sestet rhyme scheme efeffe. The meter varies from four stresses in a line:

^ / ^ ^ ^ / ^ / ^ /

‘My visa is expiring. I begin’

to six:

/ / ^ / ^ /^ / ^ /

‘Please lend me thirty, Mr Certain Death’.

Time, although regularly marked in the titles of each sonnet, escapes patterning upon closer inspection. With this not-quite-certain sonnet, Koh both suggests and subverts the poetic solution to his speaker’s problems. Verse can only offer a semblance of hope, and time borrowed from Death will have to be paid with ‘[jacked] up [...] interest’.

Just as Ip’s sonnets reveal the postcolonial stakes of his complex reader-speaker relationships, Koh’s obsession with time reveals another dimension of the interplay between ‘I’ and ‘you’. The reader is ‘Mr Certain Death’, the figure with whom the speaker pleads to buy his poetry, both literally and idiomatically. The speaker needs acceptance and money ‘right now’ in order to both shore up his shaken sense of self and survive. When the economist says that this act is irrational, he also suggests that one cannot subsist on poetry. This anxiety inflects Koh’s poem-a-day practice. More than just an abstract artistic challenge, it is also a way to produce poetry quickly enough to assemble a collection, get sales and readership, and somehow prove the pragmatic economist wrong.

In ‘April 19, Tuesday’, Koh’s handling of time describes the anxiety behind poetic production, while suggesting a way out of worrying about the future through the quotidian present. The speaker appears to compose his ‘after/ lunch poem’ in real time (37). ‘I can write this cuz I’m jobless’, he says; ‘I’ve got the afternoon to sit and stare’. The poem, Koh wants readers to believe, is the fruit of his speaker’s inability to find more productive ways of spending time. The poem largely consists of blow-by-blow descriptions of the day: morning commute, job interview, lunch, indifferent flirting, wandering, nothing particularly momentous. Most of Koh’s poems are conversational—his speaker goes further, using ‘cuz’ (‘because’), suggesting he is composing on a portable device. This feeds back into the impression that he writes, carefree, in real time.

The tension between the ‘liveness’ of the speaker and the always-already belated written word also reflects the tension between poetic vocation and ‘real’ job, between quotidian moments and time paid by monthly salary. Of course ‘liveness’ is constructed. ‘April 19, Tuesday’ fits the sonnet’s rules, even as the speaker recalls his day ‘off-the-cuff’. When he is interrupted by the School Head’s call, the poem gives ‘stage directions’—‘[stops writing]’—to suggest immediate response. Yet these directions are not external to the poem; they are part of the final rhyming couplet. The call is the sonnet’s volta, turning from description to metafictional awareness, from anxiety to anticipation. Time spent on the job and in wandering moments, structure and free-flow, are parts of the same equation. The sonnet set-up and ending turn is appropriate to this tension.

Ip and Koh’s poems question both the universality of the sonnet form and the specificity of the Singaporean subject, or the everyday moment. These sonnets cannot and must not be read the same way as those produced by other cultures; yet Ip’s Singlish and Koh’s speakers’ experiences remain largely translatable, relatable. Both collections construct speakers who, self-reflexively, broadcast a desire for their readers. On one hand, this situation can be traced to the specific difficulties of poets and poetry in and from Singapore. On the other, Koh and Ip grapple with a chosen form and language that is the product of a historically imperialistic culture, one whose poetic tradition they nonetheless engage with.

Rajeev Patke provides a wider definition of postcolonial poetry than discussed thus far:

In a more dynamic sense, postcolonial poetry shows awareness of what it means to write from a place and in a language shaped by colonial history, at a time that is not yet free from the force of that shaping. (2006: 4)

To the extent that their sonnets remain formally conservative, Koh’s and Ip’s poems make readers aware of how colonial history shapes language, and how they are ‘not yet free from the force of that shaping’. Refraining from radical deviation reflects how English language and culture, for good or ill, influences and constitutes Singaporean identity. Yet to the extent that their sonnets include local variation, Koh and Ip suggest that postcolonial literatures are vitalised, not paralysed, by their histories.

Sonnets and Loans do not offer easy solutions; both collections conclude with an incomplete bridging of the gap between poet and reader, local and global. Ip’s ‘we spoke’ dramatises this interaction as an earth-shaking historical moment:

we spoke: treaties were signed, lords overthrown,

children conceived, put through the rise and fall

of states and syllabi, of texts and thrones,

because two people spoke. (57)

Literary and imperialistic encounters are both, at root, a meeting of self and other. The aftermath, however, occurs in an ‘awkward room’ where ‘co-workers who once spoke twiddle thumbs/ while wondering how to revert[10] to one another’. The nonstandard usage of revert underlines the gap between speaker and spoken to who desire reunion, reversion to oneness, but do not achieve it.

Koh’s ‘April 30, Saturday’, concludes his meditation on time and money, relating both to each other through sex: ‘a coin is dropped/ into a bottle each time a couple fuck’ (59). These moments, crystallised into coin, are spent as lovers spend time: ‘They take the rest of their lives, seconds copped,/ to empty the decanter’. The coin stands for the everyday moment Koh values throughout, spent in ‘exact cash for food/ I enjoyed as more than friend and less than spouse’, self and other at last in a relation of more than indifference but less than commitment. The ironic final line—‘I read on a dime e pluribus unum’. The American promise of synthesis, inscribed on coin, mapped onto time, remains unfulfilled.

This essay sketches a rough outline of the problems facing postcolonial poetry in English, and the strategies writers use to turn these problems to their advantage. The sonnet emerges as a fruitful form for their purposes. No longer signifying cultural elitism while remaining familiar to elite Anglophones, the sonnet dramatises the tensions between high versus low culture, between poor readership versus a desire for wide appeal. With some willed distance from its ‘Western’ origins, the sonnet’s rhetorical and metrical properties can be exploited to embody issues of time, cultural hybridity, and reader-speaker relations. These issues may display a specifically Singaporean character in Koh and Ip’s work, but clearly have implications far wider than any particular geographic or political region.

That sonnet collections from Singaporeans have only just begun to emerge in the past few years suggests that at least some poets here feel confident in owning the form and participating in its history. Whether Koh’s and Ip’s debuts mark a new flowering of received form or committed formalists in Singapore, or whether they are mere anomalies, only time will tell. Nonetheless, they demonstrate that it is possible, even necessary, to influence and be influenced by the lineage of English poetry post-colony. Former British colonies that allow the English language in their poems cannot ignore the histories of English poetic forms, even if contemporary centres of English literary power largely ignore these productions. As in Ip’s and Koh’s poems, even if speakers and readers may never achieve communion, every asymptotic approach should, nonetheless, be taken.

[1] Toh Hsien Min, another Singaporean, has a collection of sonnets in manuscript.

[3] King of K[araoke] Song

[4] Singaporean army recruits surrender civilian identity cards for military ones.

[5] Regulates personnel movement.

[6] For boots to be polished to a reflective shine.

[7] Housing Development Board flat, government housing. Nearly 80% of Singaporeans live in a HDB, first-time buyers are usually newlyweds.

[8] Rag and bone man.

[9] Full version: karung guni, poh zhua gu sa kor, pai leh-lio, dian si ki... (‘Rag and bone, newspapers and old clothes, broken radios, televisions…’)

[10] Widely used malapropism for ‘reply’, often in a business or government setting.

Appendix A

From Sonnets from the Singlish, by Joshua Ip

k ge zhi wang attends a poetry reading.

he’s bored. they really are just reading poems.

the title’s not the least bit misleading.

where’s the performance? he wants to go home.

in karaoke, in his element,

originals are shunned. one is expected

to perform the standards before vent-

uring into new tunes. It’s called respect:

to the k gods, who echo in the ether;

to captive audiences who retain

the option to join in at the refrain.

he has the following feedback for the reader:

read me familiar stories, stanzas, quotes—

nobody wants to hear what you just wrote.

entry

this poem comes with intentions and directions clearly labeled.

this poem has been vetted, cleared, and given the once-over.

twice-over, overlooked with oversight. it has been tabled

ably to all appropriate approving fora.

this poem solemnly declares and swears it does not keep

in its possession any media. this poem is free

of any image-capturing device. it does not beep

a beep. this poem has surrendered its identity.

this poem is tucked-in, clean-shaved, and iron-creased, each last

cock-hair shaved off and burnt and tweezed with a mother’s pride,

screaming ‘inspect me’ from each seam, no dirt, no dust—

this poem is so shiny you can see your face inside.

submitted, for approval, please—i’m willing to refine it.

or let me write it in your book-in book, and maybe sign it.

chope

seems half the work of weddings nowadays

is all about the asking. bigger better

bangs and bucks, and every suitor sets a

higher bar for better men to raise:

flash mobs and fireworks and fighter rides—

the shock and aww is how a bride computes

your manhood, though the snazziest of suits

will sink without a rock of proper size.

is there an issue of sincerity

if over coffee, talk turns by and by

towards the prospect of a hdb?

would it be disrespectable if i,

while at a hawker stall, drop to a knee,

and place a tissue packet on your thigh?

rag and bone

the fossil fuels were the first to go.

then metals, steel and iron, copper, tin.

we hollowed out the hills to feed the grow-

ing appetite of mankind and machines.

we ate and shat, and ate, and shat, and shat.

and starved in cities made of shit alone,

evolving from our brittle forms to that

which lasts forever—planet styrofoam.

one man rides through the polystyrene dawn

the lord of all he sees. quite early on

he figured out earth’s going to the dumps

and fashioned a career of buying junk.

he sounds his lonely horn—karang guni—

poh chuah—gu sar kor—pai dian see kee—

‘we spoke’

hearing of this, like discovering a note

in a back drawer, from a long-lost flame

who, lovingly, at length, in longhand, wrote

the purplest of prose. what was her name?

we spoke: treaties were signed, lords overthrown,

children conceived, put through the rise and fall

of states and syllabi, of texts and thrones,

because two people spoke (and one recalled

of that which they spoke, then). life is the sum

of reported speech, the whole world turning on the

spokes of our purported conversation, and we come

eventually to the awkward room where all the

co-workers who once spoke twiddle thumbs

while wondering how to revert to one another.

From Payday Loans, by Jee Leong Koh

April 14, Thursday

For years I had been running a low fever:

Hot coals heaped by the saints onto my head;

friction from the rutting wheels of an achiever

who minded what in Singapore could be said.

Now freed from church and state, I’m a believer

in the pursuit of happiness instead.

Poetry is my chosen course, the lever

for straightening dislocations in my bed.

You read my work for indiscretions, claim

them yours, to be used only with permission.

Love, are you Priest or Law, another name

for Censor? Or is my love in remission?

I will still write like a free man on a lame

excuse: accept me, Love, with this condition.

April 13, Wednesday

Come on, straight boy, and make gay love with me.

One night of loving will not turn you queer,

if queer is what you will not bend to be.

Loving a man is but a change of gears.

Why do it with a girl, an undulating

waterbed, and stress leaks pinched too late?

Why, in an oven she loves regulating,

you stick your tray of cookie dough, and wait?

Men love themselves when they love other men;

loving themselves they know well how to give

each other head, maneuver two or ten

round the bend of straightforward relief.

What have you got to lose? Leap, acrobat!

You can always fall back on pussycat.

April 16, Saturday

Bad start: you searched the Net for me, and loved

an early poem in a style so jeweled

I blushed and stripped it down to a bright nude.

Preferring still the body shod and gloved,

you saw more than I did. How you approved

as I read Proust aloud, of the pulchritude

of blurry windows when the women screwed

each other; vaguely, vastly, you were moved.

Last night I stripped before a cheering crowd

but had eyes only for where you stood,

and then for the train window, still too proud

to ask. You answered in bed, ‘It sounded good’.

Faint praise from the beloved! How loud, how loud

I heard the glass, in virtual space, crack.

April 1, Friday

Please lend me thirty, Mr. Certain Death.

In cash. You’ll get it back on my payday,

the sum assured, with the surety of breath.

I need the loan right now to make my way.

My boyfriend doesn’t want me to move in

yet. I’m leaving school without a job.

My visa is expiring. I begin

again a sonnet when the brain’s a throb.

Last night, a Coke-drinking economist

discoursed on lenders jacking up their stall

and interest rate for those desperate or pissed,

spending their days in poverty’s deep mall.

The man concluded it’s irrational

to borrow from you, Mister, to subsist.

April 19, Tuesday

This is not a lunch poem. It’s an after

lunch poem. I can write this cuz I’m jobless.

I’ve got the afternoon to sit and stare.

This morning I rode the 6 train to Lex

to interview with the School Head. She said

she could sponsor me for an American

visa. I don’t remember what my head

said but my heart flew to my stomach. Then

I had a turkey sandwich with grilled

turkey and American cheese, and made eyes

at the huge, blond Latino behind the till.

He looked away. I cruised the park to say HI!

to the gulls. Call coming in. [stops writing]…

It was the Head. I’ve got a job waiting.

April 30, Saturday

In the first year, you said, a coin is dropped

into a bottle each time a couple fuck.

They take the rest of their lives, seconds copped,

to empty the decanter, with some luck,

coin by long coin. I think of your loose change

tossed into the cup—quarters, pennies, dimes

—silver and copper that come from a range

of corduroy you wore at different times,

and become sad. Then I recall you would

pick up some coins before we left the house

so as to pay with exact cash for food

I enjoyed as more than friend and less than spouse.

Over the cup, thinking of memory’s sum,

I read on a dime e pluribus unum.

Appendix B

2014 ‘SingPoWriMo’, Facebook group, at https://www.facebook.com/groups/singpowrimo (accessed 30 April 2017)

2015 National Literary Reading and Writing Survey 2015, Singapore: National Arts Council, at https://www.nac.gov.sg/dam/jcr:72e71144-91c4-430c-bbe0-8d7a3ec358e4 (accessed 8 September 2017)

Bhabha, H 2001 ‘Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse’, in P Rice and P Waugh (eds) Modern Literary Theory: A Reader. 4th Edition, London: Hodder Arnold, 380-7

Grant, M 2008 “A scanty plot of ground:” Navigating Identity and the Archive in English Indian Sonnets, Concordia University Montreal, Quebec: MA Thesis

Hilson, J (ed.) 2008 ‘Introduction’, in The Reality Street Book of Sonnets, East Sussex: Reality Street Editions, 8-18

Ip, J 2012 Sonnets from the Singlish, Singapore: Math Paper Press

Ip, J 2014 ‘Preface’, in Koh J L Payday Loans, Singapore: Math Paper Press, xvii-xxiii

Ip, J 2012 ‘sonnets from the singlish—origins’, personal blog, 5 Jul, at http://www.joshuaip.com/2/post/2012/07/sonnets-from-the-singlish-origins.html (accessed 30 April 2017)

Koh, J L 2014 Payday Loans, Singapore: Math Paper Press

Macaulay, T 1835 ‘Minute by the Hon'ble T. B. Macaulay, dated the 2nd February 1835’, in H Sharp (ed.) Bureau of Education. Selections from Educational Records, Part I (1781-1839), Delhi: National Archives of India, 107-17.

McLuhan, M 1964 Understanding media: the extensions of man, New York: McGraw-Hill

Patke, R 2006 ‘Poetry and Postcoloniality’ in Postcolonial Poetry in English, Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 3-28

Poon, A, P Holden and S Lim (eds) 2009 ‘General Introduction’, in Writing Singapore: An Historical Anthology of Singapore Literature, Singapore: NUS Press, xxi-vi

Robertson, R 2001 ‘Comments on the ‘Global Triad’ and ‘Glocalization’’, in Globalization and Indigenous Culture, 15 May, at http://www2.kokugakuin.ac.jp/ijcc/wp/global/15robertson.html (accessed 30 April 2017)

Sanderlin, G 1939 ‘The Repute of Shakespeare's Sonnets in the Early Nineteenth

Century’, in Modern Language Notes Vol. 54, No. 6, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 462-6

Thorson, M 2003 ‘Announcing NaPoWriMo’, versAtile, 17 Mar, at http://www.reenhead.com/varchives/2003_03_16_varchives.php#90858622#90858622 (accessed 30 April 2017)