Introduction

I once read that after Kurt Cobain died Courtney Love gave all his clothes to the Goodwill. Their daughter didn’t need a pile of baggy sweaters or torn jeans to remember him by, or something like that, it said. This anecdote has hung in my mind like one of those ill-fitting sweaters ever since. What has captivated me most about this story is the prospect of random people walking around in Kurt Cobain’s clothing, masquerading as rock stars, without knowing it.

This paper offers an exegetical account of my efforts to materialise the poetics of Kurt’s missing shirts and the contingencies that inevitably arise when attempting to creatively work through tragic circumstances. I outline my creative response to Courtney Love’s ‘throw away’ line and the image it produces of celebrity fashion cut loose. I discuss the experimental practice emerging from my engagement with the fabric of memory and flannel and how corresponds to my broader interests in photography, musical cultures, melancholy and commemorative gestures.

Celebrity skin and falling stars

My interest in the anecdote attributed to Love relates to my own visual arts practice in a number of ways. In the first instance, finding this story and repurposing it to make something else describes the inspirational process underpinning my practice: as a reworking of objects and materials that already exist in the world. Other points of connection include explorations in the visualisation of music (Alder 2010; Frederick 2010; 2015), the tensions between the quotidian and iconicity (Frederick 2014) and working with found media to express themes of obsolescence, celebrity, fandom and melancholy (Frederick 2013; 2017). So in many ways the story I describe above may be considered a knot or entanglement of threads that were already running through my creative practice. In my most recent engagement with popular music and celebrity, in the exhibition Faded Crush, I sought to explore some of the ways in which fandom is enacted. My video mashups of ‘Crimson and Clover’, ‘Because the Night’, and ‘Ziggy Stardust’ focused on everyday people making cover versions of songs they love. It addresses how, by recording their own version within their domestic interior and broadcasting it to the world through contemporary mass media like YouTube, these individuals perceive, inhabit and reimagine the persona of the rock star. Such performances are an act of devotion and a re-enactment; they are both deeply personal and public displays that complicate the boundaries between anonymity and stardom, the stage and the living room, and the identities of fan and celebrity.

As Catherine Soussloff (1997) discusses, ‘the artist’ is a culturally constructed concept. Artists themselves are complicit in this creation process by intentionally and, sometimes inadvertently, developing and promoting certain identity formations. For musicians this is not limited to the sonic ‘products’ they make but extends to the way they look and move and what they say and wear. Elvis may best embody a convergence of phenomena – of musical and media innovations, youth consumer culture, good looks and radical gestures – which enabled rock stardom to happen; however Amy Fletcher (2011) argues that the persona of the rock star was actually crafted by Jim Morrison. If Morrison’s fast rise and demise provide any indication, the mold that he cast ensures that the rock star ends up broken.

Beyond individually emulating any template of doomed rock star, musicians themselves have played an active role in valorising the rock star as a tragic figure. This story is no better told than in the lyrics of Bad Company’s Shooting Star, but the sentiment of living fast and dying young is peppered through a vast array of musical genres (from Don McLean to the Circle Jerks or Iron Maiden). In one respect this bearing speaks of a sensitivity to the capricious cycles of the popular music industry and reflects on the Faustian pact of celebrity. In another sense the ‘better to burn out than to fade away’1 attitude suggests a dis-ease with living in the spotlight, or a resigning to fate, a position which Kurt Cobain himself appears to reiterate by quoting the phrase in his suicide note. In addition to fulfilling the destiny of tragic rock figure, Cobain’s death by his own hand also places him in the romantic tradition of the misfit artist or self-destructive ‘genius’ (Strong 2011). Ironically, for many fans and critics Cobain’s fall into a premature death cemented his celebrity and elevated his star higher in the mythology of popular music cultures. This goes some way towards explaining the specific ways in which fans commemorate his life.

Fletcher makes a further compelling point, suggesting how we might approach the rock star figure. and how we may comprehend their status and enigma.2 She suggests we might better comprehend their status and enigma by considering their reception rather than their biography. To paraphrase Fletcher (2011: 150) the key is to stop trying to make sense of his life, to stop looking for the real person, but to focus instead on responses to his story, both then and since his death. To ask, in short, why does Kurt Cobain matter? And why do people make art about him even twenty years after his death?3

Discarded flannel

The rock music subgenre and ‘anti-fashion’ movement grunge emerged in the 1980s in and around the city of Seattle, USA. Initially an underground music scene with roots in punk and heavy metal (Bennett 2001), grunge became a global phenomenon in the early 1990s with the commercial success of Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden and other bands. Like punk, grunge was as much an attitude and style as it was a musical genre. That is, clothing was an essential part of grunge’s image and a mode of self-identification for fans, even though the low-key look was intended to not make a statement. What is intriguing about this aspect of grunge — the appearance — is that unlike gothic, rave, rap or metal, the fashion should not seem ‘put on’ or contrived. On the one hand it reflected the everyday realities of the environment in which grunge thrived; ‘we wore flannels ’cause it was cold out and everybody’s dad worked at the mill’ (Patty Schemel, quoted in Wolfe & Shifflett 2017). But on the other, it was an ironic double-bluff designed to undo conformism: rather than care how you looked, you had to look like you couldn’t care less.4 In keeping with this sentiment of ‘nothin’ special’ and the origins of the movement in the Pacific Northwest, the loose-fitting flannel or plaid work shirt5 quickly became one of grunge’s leitmotifs.

As the lead singer and songwriter of Nirvana, Kurt Cobain was quickly catapulted to superstardom when the ‘Seattle sound’ hit the mainstream, and subsequently Cobain’s ‘face and music have come to epitomize the grunge era, and, in fact ‘The 90s’ more generally’ (Strong 2011: 85).

Considering the plaid shirt as an extension of tartan, and in the context of rock music, Percival suggests that it echoes notions of truth, authenticity and blue-collar origins:

Cobain’s plaid shirt was both ‘natural’ (manual workers in his hometown wore them) but arguably also ironic … By wearing the plaid shirt, Cobain celebrated his origins whilst knowing that large numbers of Americans who dressed similarly would not share his values. (Percival 2010: 207)

Prior to achieving international fame Cobain met Courtney Love, guitarist and lead singer of alternative rock band Hole. Before long they married, had a child and independently recorded albums that earned significant critical acclaim. In the short space of five years Nirvana had released three studio albums, numerous singles and videos, and had toured extensively within North America and Europe. After Cobain took his life in 1994, the group disbanded and the millennium neared its close. Contemporary music and fashion left grunge behind for something new, although both Cobain and his band remain influential among musicians and fans to this day.6

‘With the lights out, it’s less dangerous’7

In the lumberjack territory of Washington State, flannel shirts and torn jeans are as common as the mud and rain. If Cobain’s clothing really did turn up at a thrift store in Seattle, no one would even notice. His general attire made him a kind of everyman who blended in, rather than making him stand out. This not only makes it entirely plausible that people are walking around in the guise of Kurt Cobain, but it adds a perfect pathos to Courtney Love’s gesture. For not only would the discard of Cobain’s clothing be the ultimate affirmation of grunge’s anti-fashion statement, it is quite likely that the thrift store is where Cobain bought his clothes in the first place. In the end, like some tragic metaphor for the cycle of life and cosmic return, it’s in the thrift store of Seattle that the image of grunge, and Kurt’s shirts, come full circle.

My first efforts to activate the complex poetics and awkward beauty that I sensed in this story was to seek out Kurt’s shirts for myself. Because I had grown up in Seattle, the city where Cobain lived his last years and unexpectedly died, it wasn’t hard for me to imagine where his former threads might find rebirth. The flagship Goodwill outlet, south of downtown just off I5, was a local landmark, and I had occasionally shopped there as well as at other thrift stores in the Central and U-Districts of the city. So my starting point for this exploration was fairly straightforward. Next time I was in Seattle I would visit some thrift stores, go to the men’s section and proceed to purchase a number of flannel shirts. At that point, I didn’t know exactly what I would do with them. I thought I might unstitch certain sections and photograph them as fragments. I had a vision of a sleeve suspended like Maret’s lifeless arm slung over the edge of the bath in David’s painting The Death of Maret (1793). There was also the prospect of using the fabric as a canvas on which I might paint or print.

After some thought I decided to trial making photograms, one of the oldest photographic techniques, not only because it relies on an indexical relationship with an object to make the image, but also because of its pure simplicity. There is no camera; only light, paper and chemistry.8 Moreover, a photogram is made by placing an object in direct contact with the photosensitive substrate, and whatever light passes through or around the object will register on the paper. So the object is an essential agent in the construction of the image. Hence, the photogram process creates an intriguing tension between recording something that is real (the object) and performing an abstraction of that same object. It is simultaneously a representational and non-representational process. To my way of thinking this conceptually illuminates the very threads of this story: is it real or just a phantom footnote in rock-n-roll mythology?

Unlike black-and-white photography, with colour printing there is no safe light, and every stage of the process is undertaken in complete darkness. As a result, you can’t see what image you might get until it is too late to change it, when the light of the enlarger is turned on to make the exposure. Working with the lights out leads to a deeply sensorial engagement with the materials of the image-making process. You become attuned to the boundaries of your body, literally touching your way through every step: from removing the paper from its protective packaging and feeling for the right way up (the emulsion) to arranging the shirt and setting the correct exposure and proportion of CMYK filtration. Each juncture is a haptic encounter in which your fingers become a surrogate for sight. This kind of photography takes time, and much of it is spent playing and fumbling as other senses gradually take prominence and make up for the temporary loss of vision.

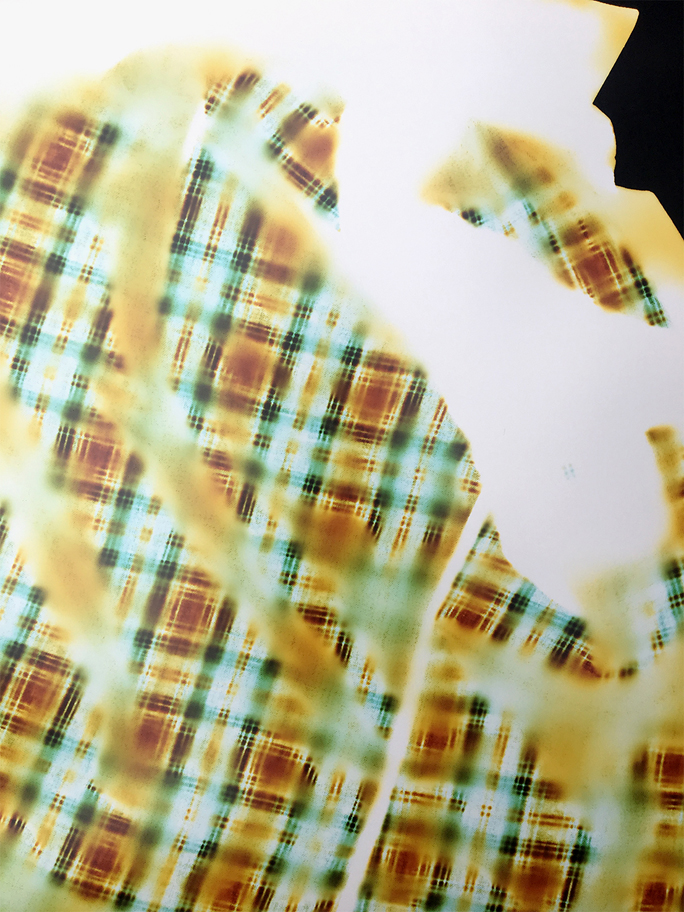

Making this series I first concentrated on the pattern of the shirt because this was essential to communicating plaid/flannel, and I spread the shirt out into a flat 2-dimensional plane to give the paper an even exposure. This was more difficult to achieve than it sounds, and upon seeing the results I realised that I shouldn’t try to iron out the folds and contours of the shirt because it removed the dynamism and sense of the body it is designed to wrap around (Fig 1). With some parts of the fabric flat against the paper and other sections of the shirt gathered or overlapping, the image emerged with more depth, both partially ‘in focus’ and also blown out in places, or blurry.

The sense of uncertainty and lack of control that darkness can bring forth requires, on behalf of the maker, a degree of both attunement and surrender to materials and process. Hence, through the making of the photogram series based on the shirts I had recovered in Seattle, I became acutely aware of the tactility of flannel. It also brought the physical and sensory qualities of the fabric into sharper focus: some shirts had a thicker weave, some were a little threadbare, and certain fibres blocked the light more thoroughly than others. It seemed almost as though the photosensitive paper was wearing the shirt, like a body might.

As touch became central to my working process the fabric enlivened beneath my fingertips bringing home both the materiality of the referent and the substance of my medium, that is, ‘the “thingness” of photographs’ (Willumson 2004: 77). Skin, both real and metaphoric, came to preoccupy my thinking. I was reminded of the ‘imagined exchange of touches between subject, photograph, and viewer’ (Batchen 2001: 21) that photography precipitates:

The photograph is literally an emanation of the referent. From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here ... A sort of umbilical cord links the body of the photographed thing to my gaze. (Barthes 1981: 80–81)

Barthes’ expression of photographic ‘vision as a form of touch’ (Batchen 2001: 21) acquires a deeper resonance with the photogram technique because it involves a direct contact, communicating a potential for transference — of something rubbing off onto something else. Just as the shirt had once brushed against the skin of a human body (possibly Kurt), so too the emulsion of the photographic paper comes into contact with the fabric. In this exchange of skins a doubling takes place: the photographic print stands in for the body, inhabiting and holding the shape of the shirt, just as it imprints the shirt that once enfolded the person who wore it. In this way person and print share the folds of the flannel.9

Clothing in photography and other memento mori

Photographers have long recognised the intimacy and poignancy of clothing and other personal effects through its capacity ‘to evoke a physical human presence without in any way denying … the fact of its absence’ (Ferran 2000: 164). Contemporary photographers Isiuchi Miyako, Anne Ferran and Oliver Toscani, for example, have all made images from clothing once worn by living people now dead. The incorporation of disembodied clothing in a photograph can be confronting because the absent individual has become the inherent subject of the image. However, such images may also guide us in addressing the realities of death, loss and grieving. In some cases they may enact what Best (2016) describes as a reparative strategy, in which an artist enables the viewer to engage with difficult or distressing issues through an aesthetic register, rather than turn away from them through ‘indifference, compassion fatigue and shame’ (Best 2016: 7). For example, Isiuchi Miyako’s photographs of the garments of people who died in the bombing of Hiroshima would seem to achieve the kind of affect that permits viewers to begin to process the traumatic event and aftermath of atomic destruction.

While I am not suggesting that my work is performing a ‘reparative aesthetics’ (Best 2016), it remains important to recognise this convergence (of clothing, photography, death) as part of my working context. I am conscious that the theme of death pervades both the origin story of this artwork (the discard of Cobain’s clothing)10 and the photographic medium more broadly. Indeed, it was my growing awareness of the pervasiveness of this melancholic theme in both musical cultures (Jones & Jensen 2005; Strong & Lebrung 2015) and photographic theory (Barthes 1981; Batchen 2004; Edwards 1998; Sontag 1979) that directed me to considering the role of remembrance more explicitly.

Although I was pleased with the corpus of photograms I had made from the thrift store clothing recovered in Seattle, and went on to exhibit them in a curated show (Broker 2018),11 through the process of making I became more attentive to how photographs perform as devices of mourning. And in thinking about the photo as a thing I had made from other things, I found myself drawn into wanting to make even more ‘solid’ objects. In turn, this led me looking for other ways I might rematerialise the flannel fabric as memento mori.

The relationship between photography, death, and clothing evident in the work of others also led me into other photographic practices and histories, specifically involving material gestures of memorialisation and other objects of ‘enshrining activity’ (Kohara 2011). I returned to a discourse of photography that addresses the physicality of the medium (e.g. Edwards & Hart 2004) and I looked more closely at the visual history of photo-jewellery, keepsakes and small photographs exchanged and worn on the body. As Geoffrey Batchen points out, it is through such objects as pendants, brooches and lockets containing portraits that ‘the photograph becomes an extension of the wearer, or more precisely we become a self-conscious prosthesis to the body of photography’ (2004: 36). This inspired me to want to make something small, portable and handheld that might incorporate the photograms or swatches of the shirts themselves. What came to mind were the nineteenth-century daguerreotype cases with their rich velvet interiors that cushion the portrait of a loved one. In such memento mori, the viewer is brought into bodily contact with the likeness of the remembered, a fact reinforced by the addition of a lock of hair. I thought I might try to make smaller photograms and pair them, perhaps including a swatch of flannel instead of hair.

Material reveries and liner notes

Transitioning this project into ceramics came from a desire to extend the fleeting presence of the photogram shirts into a more visceral physical form, and bring the haptic nature of the darkroom experience out into the open. Initially this simply involved printing a photograph of a flannel shirt on a slab of bisque earthenware (Fig 2). The ceramic flannel fragment produced a palpable tactility that reinforced the notion of carnal knowledge discussed by Barthes (1981) and Batchen (2001), and sparked an ongoing dialogue between ceramics and the photographic object that led me in a number of directions.

My loose investigation of ceramics probably reflects my exposure to a new medium and suite of practices. In restrospect I can see that the departure from my comfort zone of photography meant my unschooled and improvised approach to ceramics corresponded to the ‘“anti-talent” prized within the punk formulations of authenticity’ (Wood 2011: 335) admired and emulated by grunge musicians.

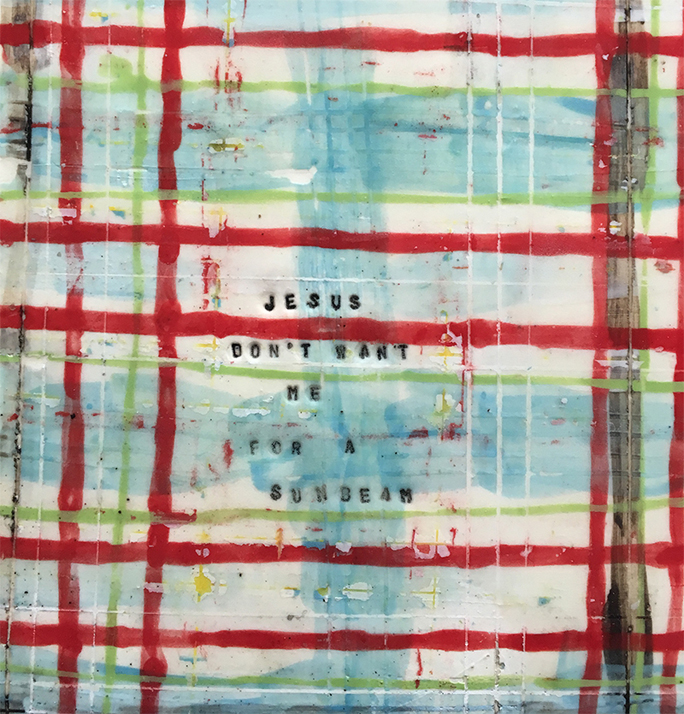

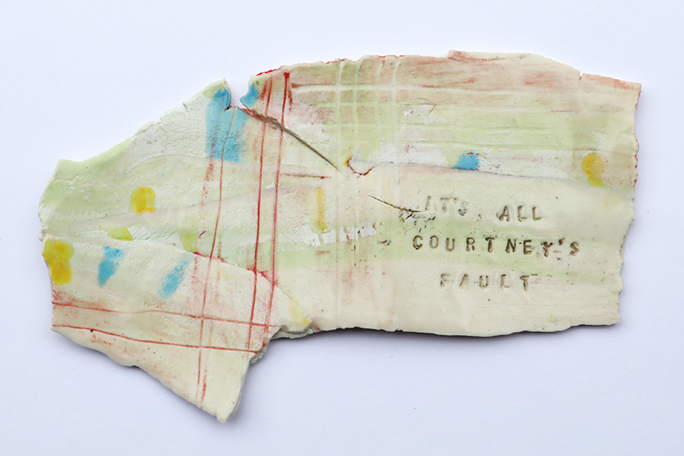

One of the methods I adopted involved making my own plaid patterns in coloured clay slip (Fig 3), initially for the purpose of making small tiles which might fit within a contemporary version of a daguerreotype-like hand-held case (Fig 4). One approach was to glaze earthenware tiles and work back into the surface; another was to apply coloured slip in a layering method, then scratching into this fine veneer before pouring a final layer of slip as a backing support. This was then peeled away to reveal a palimpsest of colour and line (see opening image). The latter technique has a certain synergy with the colour darkroom process because you may anticipate but cannot see the result of your actions until after it is complete.

The intuitive and gestural engagement with the clay to produce my own clay flannel was deeply satisfying, although the thinness of the slip was more vulnerable to breakage than the thicker tiles, and at times could be frustrating. Yet the fragility of the clay body also seemed an apt metaphor for both memory and the ailments that afflicted Cobain and propelled his expressive energy (Wood 2011). Moreover, as my project developed, I realised how this vulnerability allowed me to tear the clay fabric and further edit the shape of my flannel ceramics into poetic shards or word fragments. The rough edges and raw distressed surfaces of slip were also visually compelling, in part because they were imperfect and ‘unfinished’ rather than clean and smoothed over. They give an indication of my unskilled status as a ceramicist, and an apparent sense of carelessness — not to be confused with lack of commitment — which is reminiscent of the authentic DIY ideals and scarred aesthetics of grunge (Fricke 2013).

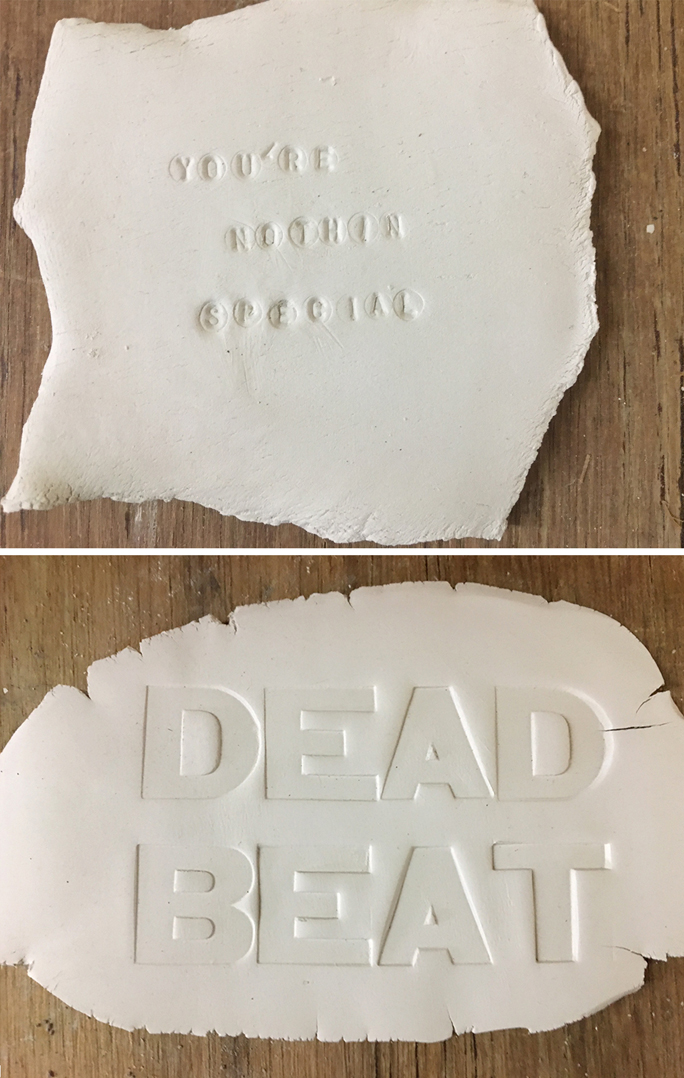

Before long I began using a small set of letter punches to incorporate text into the plaid image. I am not clear what motivated me to do this; maybe it’s because the whole idea for the project came to me from the written page in the first place. Whatever it was, returning to the word seemed to make some kind of sense, and text came quite naturally, in the form of phrases or word pairings. Some lines of text suggested song lyrics or quotes (from musicians, fans or journalists) and brought a sense of the spoken voice (Fig 5); other word assemblages were less literal, odd assertions in which it is not clear either who is speaking or to whom the words are directed (Fig 6). Some of the word pairings are incongruent or deviations in spelling (e.g. Kurtney is a bitch).

Although these phrases emerged quite intuitively, I initially felt uncertain about their efficacy or usage (was Kurt really a kunt?). Over time, I began to loosen up, recognising this improvisation as a kind of multivocality. This was not my real voice or sentiments. Which is not to say that the words weren’t meaningful, or intentional. After all, what is more direct than a script that has been carved and hardened at searing temperatures? It’s simply that I took on the persona of the lyricist who puts on a character to create their work. Despite a growing confidence with this mode of expression, it remains difficult to articulate some of my decisions12 regarding these word formations, and I am conflicted by attempting to explain them. Who is it addressing? What is it saying? Who is speaking? Despite my own lack of understanding of where these phrases came from, it seemed in keeping with Cobain’s vocal phrasing: ‘words that don’t necessarily have their expected meanings can be used descriptively in a sentence as art. True English is so fucking boring’ (Cobain 2002: 175; cited Wood 2011: 335). The meaning of Cobain’s lyrics could be obscure, ironic and at times unintelligible,13 and his vocal timbres and guttural singing made his singing often incomprehensible.

It is only after recent reflection on my own approach to word selection and composition that I became aware that my own ‘material poetics’ in some ways resonates with the kind of cryptic ‘primal sincerity’ that Cobain adopted in his writing (Wood 2011). As Jessica Wood (2011: 346) describes: ‘fragments in the Journals show Cobain writing a word over and over, gradually chancing upon “meaningful” homonyms’ and invented spellings. This wordplay of free association meant that the lyrics in some of Cobain’s own songs don’t seem to make literal ‘sense’, and nor did he make efforts to explain them. ‘Maybe he just liked to keep people guessing’, bandmate Krist Novoselic suggests (Fricke 2013), but Wood argues that the inexplicability and guttural expression behind many of Cobain’s lyrics evokes an authenticity that reaffirms his position as an independent rather than a mainstream musician.14

Regardless of my inability to pinpoint the source of their derivation, these utterances from nowhere in particular, which I now refer to as Liner Notes, became integral to the substance of all ceramic preparations going forward (Fig 7). The form and subject of this text took different directions in terms of content and application. Wordplay, in which the incongruity or mismatch of certain words also evolved quite intuitively. Like the words and slippages between text and clay, the techniques of inscription varied as I worked through how this affected the way different sentiments were conveyed and received. My experimentation with wordplay extended to its material expression as I tested hand carving directly into the clay, pressing type to create a debossed effect, and printing onto fired bisque using a flatbed inkjet printer. The shape, size and form of these tests varied quite considerably.

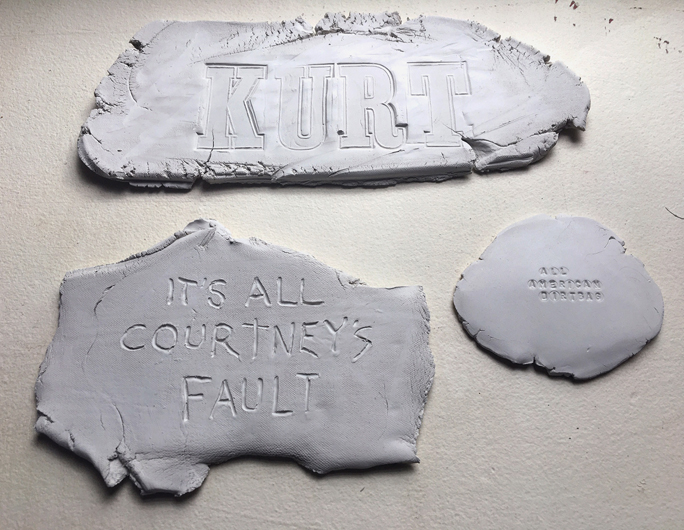

To illustrate, one example is my working of the phrase ‘It’s all Courtney’s fault’ which I trialed as several iterations. These included a gestural mark directly into clay (Fig 7), as letters impressed into hand-worked slip (Fig 8) and as digitally printed white text floating against a plaid shirt background (Fig 9). The surface treatment of the latter is conceptually suitable, because it speaks to outward appearances, the superficial and is merely skin deep, whereas the hand-carved expression conveys a certain menace that is perhaps more indicative of the vitriol Love has faced.

The text itself comments on the public reception of Courtney Love and the insults she has weathered through her association with Cobain (Fig 10). In the immediate aftermath of Cobain’s passing, considerable angst was directed at her despite the fact that she had suffered a significant personal tragedy. Love was blamed for all manner of things, including Cobain’s death, and continues to be criticised for the handling of his legacy.15 With this in mind I was prompted to suggest, in material terms, not only Love’s presence in Cobain’s life but the gendered aspect of the ‘monstrous feminine’ in media channels (Creed 1993) that has appeared in the public reportage of their relationship and its awful ending, and to some extent Love’s career since.

What is evident in this example is the vast array of options that develop through the making process and how that visual arts enquiry is an entangled process of questioning, reflection and search for resolution that leads to insight. It is only through the work and play with materials that I realised what I was trying to do and to convey. The fragmentation that has emerged and persists as I attend to this project, is partly an intuitive response to the origin story of the ‘missing’ parts of Cobain’s wardrobe and the fleeting glimpses of memory (Fig 11). The fragments of my practice reflect the fragmentary nature of the whole story. Like lines from an incomplete poem that continues to be written, they are early drafts and broken scribblings towards the telling of story that itself remains inherently sketchy and open to many endings.

Conclusion

This project, an ongoing encounter with material poetics, began as a line from a story I picked up unexpectedly. Recalling it some years later but with no further details, I can’t help but wonder if I might have made it up in the first place. Did it actually happen? Is it true? Who knows. Not me. And does it even matter anyway? Nor am I certain of where this narrative/project will lead next, or how it will conclude. I remain confident in letting the material guide me from, back and beyond the words that first inspired me, like the fabric flannel that folds, and threads that unravel, as it reforms into something else.

What I can say is that the more I work with flannel — the very fabric of the story — the more I move away from the beginning and the anecdote that led me to it. In many ways it is no longer about Kurt and Courtney at all, but rather about the poetics and possibilities of storytelling, in and across a variety of media. It is also about loss and remembering and the fleeting presence of our own mortality. It explores what people choose to discard and what they choose to save or remake, and the regimes of value such decisions necessarily entail. In effect it is more about the afterlives of people and things, and shows that objects too have life histories and tell stories. What we do with those objects and stories is a matter for us to explore and make our own. Finally, it is about how we make matter out of myths and myths out of matter. I am comfortable that my recollection, however flawed, is all that I have to go on, and trust that the ambiguities of memory, processes of mythmaking and prospect of fiction (whether on behalf of my own memory or Courtney’s account in the first place16) enable the narrative to unbutton, unfold, open up and let the light in.

Notes

1 A now well-known expression which was first coined by Neil Young in his 1979 song My My, Hey Hey (Out of the Blue).

2 Fletcher is specifically addressing the case of Jim Morrison, but I believe her point has broader application.

3 Professional artists who have specifically referenced Cobain or produced devotions of a sort include Douglas Gordon, Dexter Dalwood and Scott Redford. One recent iteration by Adrian Villar Rojas, an effigy of Cobain made of unfired clay, prompted art critic Jonathon Jones (2013) to question ‘can art save the world?’. There have also been specific art exhibitions using Cobain’s death as a curatorial impulse, including After Kurt and Don’t Kurt Cobain.

4 With specific reference to Cobain’s attire, the shapelessness or lumpiness of his dress disguises his thin frame while also exposing a discomfort with his own self-image. See Wood 2011 for further discussion on Cobain’s marginalised body and the authentic status it afforded his creative practice.

5 In America the term plaid is commonly used, whereas in Australia the term is flannel or flannie. I use the terms flannel and plaid interchangeably here.

6 Despite this fact, as Wood (2011: 347) notes ‘there has been surprisingly little scholarship around Nirvana or its front man’.

7 A line from the chorus of Smells Like Teen Spirit, Nirvana’s biggest hit.

8 One might suggest this analogue technique provides a visual parallel to a ‘lo-fi’ sound recording approach.

9 Specifically in relation to clothing and fashion, see Smelik (2015) on the Deleuzian concept of the fold as a process of becoming.

10 It can be easy to make light of fame and forget that we are discussing real individuals. It is not my intention to trivialise either the effects of Cobain’s suicide on those who knew him or how celebrity death may result in real and lasting effects on fans.

11 I informally refer to this series as Kurt’s Shirts, although each unique photograms is labeled with a number in the series CMYKurt, which references the colour filtration and ‘carnal medium’ of light (Barthes 1981: 81) that were integral to making the artwork.

12 For example, only as I was writing this paper did I realise why I might have impressed the letter X repeatedly into a slab of clay. In hindsight I recall thinking ‘what am I doing? Are these kisses? Am I indicating something x-rated?’ I recognise it now in relation to Cobain’s place as the voice of a generation, that was labeled Gen X.

13 Wood (2011:331) argues that Cobain used ‘unintelligible lyrics as a means to signal the “authenticity” of his art’, a point that seems to be confirmed by Nirvana bass player Krist Novoselic in his interview with David Fricke (2013). In the song Bloom Cobain seems to directly signal this irony and how it is lost on some fans, who sing along to words they don’t understand.

14 Percival (2010: 208) argues a similar position in relation to Cobain’s clothing, suggesting plaid was deployed to convey an authenticity ‘built around a commitment to principles of independence from a corporate music industry’.

14 To her credit, Love did live through it and continued to pursue a musical and film career as well as raising her daughter into adulthood.

16 According to Jeremy Thackray (2015) neither Kurt nor Courtney were above ‘distorting history’ and making up versions of stories when the situation warranted it.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the ceramics workshop of the ANU School of Art & Design for their support in facilitating my experimentation with ceramics, particularly Joanne Searle for sharing her knowledge and guidance. I thank the editors and two anonymous reviewers for their comments during the development of this paper. This paper was written while I was a recipient of an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Award (DE170101351).

Alder, A 2013 ‘RPM: Revolutions in Print Media’, Imprint

Barthes, R 1981 Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, New York: Hill and Wang

Batchen, G 2004 Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance, New York: Princeton Architectural Press

Batchen, G 2001 ‘Carnal Knowledge’, Art Journal 60.1: 21–23, DOI 10.1080/00043249.2001.10792044

Bennett, A 2001 Cultures of Popular Music, Buckingham, UK: Philadelphia Open University Press

Best, S. 2016 Reparative Aesthetics: Witnessing in Contemporary Art Photography, Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic

Broker, D 2018 ‘Obsessive Impulsion’, Canberra Contemporary Art Space, 27 April—23 June

Creed, B 1993 The Monstrous-Feminine Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis, London: Routledge

Edwards, E and J Hart (eds) 2004 Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images, London and New York: Routledge

Edwards, P 1998 ‘Against the Photograph as Memento Mori’, History of Photography 22.4 (Winter): 380–84

Ferran, A 2000 ‘Longer than Life’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 1.1: 162-70, DOI 10.1080/14434318.2000.11432660

Fletcher, AL 2011 ‘Another Lost Angel: The Visual Genius of Jim Morrison’, The International Journal of the Image 1.4: 141-51

Frederick, UK 2010 Easy Listening, solo exhibition, Megalo Arts Space, Watson

Frederick, UK 2013 Lament, solo exhibition, Canberra Contemporary Art Space, Canberra

Frederick, UK 2014 On and Off the Road: Creative Intersections between Cars and Art, PhD thesis, The Australian National University, Canberra

Frederick, UK 2015 The Record Store, solo exhibition, Watch this Space, ARI, Alice Springs

Frederick, UK 2017 Faded Crush, solo exhibition, M16 Art Space, Canberra

Fricke, D 2013 ‘Krist Novoselic on Kurt's Writing Process and the 'In Utero' Aesthetic’, Rolling Stone, 3 October, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/krist-novoselic-on-kurts-writing-process-and-the-in-utero-aesthetic-20131003 (accessed 14 March 2018)

Jones, J 2013 ‘Adrian Villar Rojas: Why I Made Kurt Cobain out of Clay’, The Guardian 19 September, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/sep/19/adrian-villar-rojas-studio (accessed 19 January 2018)

Jones, S and J Jensen (eds) 2005 After as Afterimage: Understanding Posthumous Fame, New York: Peter Lang

Kohara, M 2010 ‘Between Life and Death, Public and Private, East and West’, in G Batchen with essays by Y Kai and M Kohara, Suspending Time: Life — Photography — Death, Nagaizumi-cho, Shizuoka: Izu Photo Museum, Nohara, 230–47

Percival, JM 2010 ‘Rock, Pop and Tartan’, in I Brown (ed), From Tartan to Tartanry: Scottish Culture, History and Myth, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 195–211

Smelik, A 2015 ‘Fashioning the Fold: Multiple Becomings’, in R Dolphijn (ed), This Deleuzian Century: Art, Activism, Life, Leiden: Brill. 37-56

Sontag, S 1979 On Photography, Harmondsworth: Penguin

Sousloff, CM 1997 The Absolute Artist: The Historiography of a Concept, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Strong, C 2011 Grunge: Music and Memory, Farnham, Surrey and Burlington, VA: Ashgate

Strong, C and B Lebrun (eds) 2015 Death and the Rock Star, Abingdon, UK & New York: Ashgate

Thackray, J 2015 ‘In Search of Nirvana: Why Nirvana: The True Story Could Never Be “True”’, Popular Music and Society 38.2: 194-207, DOI 10.1080/03007766.2014.994326

Willumson, G 2004 ‘Making Meaning: Displaced Materiality in the Library and Art Museum’, in E Edwards and J Hart (eds), Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images, London and New York: Routledge, 65–83

Wolfe, A and J Shifflett 2017 ‘“I’m In The Band” Ep.4: Patty Schemel (Hole) on making zines with Kurt and Courtney’, Tidal, 15 November, at http://read.tidal.com/article/im-in-the-band-ep-4-patty-schemel-hole-on-making-zines-with-kurt-and-courtney (accessed 16 February 2018)

Wood, J 2011 ‘Pained Expression: Metaphors of Sickness and Signs of “Authenticity” in Kurt Cobain’s Journals’, Popular Music 30.3: 331–49