To what extent does the poetic line bear the stamp of a particular poetic personality? Is that, in any case, a desirable thing? Do individual poets have their own rules about how the line behaves – the distance it travels, to what purpose, and when and how it breaks – or is it constantly adapted for purpose? Are poets even aware of their process and, if so, honest and open about it? In this paper I consider the various (and varying) uses of the line by poets who have influenced me most profoundly, with examples from my own work to demonstrate my learning and further experiments. Specific reference is made to the influence of cinematic editing, and the role of the line in a poem’s essential memorability. Also addressed are the different effects of the stretch and breaking of the line on the page and when orally delivered.

Beginning at the end

When people start talking about enjambment and line endings, I always shut them up. This is not something to talk about, this is a private matter, it’s up to the poet. (Tate n.d.)

If all poets were as reticent on the subject as James Tate, we should know precious little about how and why poets choose to do that strange thing, unique to poetry – move deliberately from one line to the next. We can of course, as critics, comment on the effect, but Tate’s comment would seem to suggest even that should be resisted.

One only needs to glance at the poems by James Tate on the Poetry Foundation website (n.d.) to feel frustrated by his reticence. What does he think he is doing, breaking his first lines after the definite article?

Millie was in the backyard hanging the

laundry. (‘At the Clothesline’)

I got a call from the White House, from the

President himself, asking me if I’d do him a personal

favor. (‘Bounden Duty’)

Are we not supposed to contemplate those very prominent, seemingly unnatural breaks? Are we not to be interested in the way the poem works? We might well become suspicious of Tate’s defensiveness. Might it just be the case that the poet has no real justification for his movements on the page? Is such ‘free verse’ merely sloppy? In that second example, Tate breaks the next line after an adjective, another questionable tactic. Philip Larkin, interviewed by Robert Phillips, states as one of his own ‘private rules’: ‘Never split an adjective and its noun’ (Larkin in Phillips 2003: 19). Thus we see Larkin and Tate in fundamental disagreement, yet united by their use of that curious word, ‘private’.

Larkin’s statement comes in the context of a more general comment about poetic craft: ‘Writing poetry is playing off the natural rhythms and word order of speech against the artificialities of rhyme and meter’ (ibid.). The consequence is creative tension, but also compromise – and, sometimes, broken rules. In ‘Sad Steps’, working within his own rhyme scheme, he gives us ‘The hardness and the brightness and the plain / Far-reaching singleness of that wide stare’ (Larkin 1974: 32). ‘Plain’ is needed as a rhyme for the subsequent ‘pain’ and ‘again’, but it is also, surely, a meaningful place to shift, emphasising the gulf between ‘plain’ and ‘far-reaching’; in any case, the second adjective, adjacent to the noun, preserves Larkin’s ‘rule’. In ‘Solar’, however, there is a more significant surprise: ‘Heat is the echo of your / Gold. (ibid.: 33) This is a poem unconstrained by the ‘artificialities’ Larkin mentions. Instead, it is the wilful line break itself that seems artificial; as with the Tate examples, it is not in any sense necessary, and therefore draws attention to itself. Furthermore, ‘Gold’ is a one-word line, concluding the stanza. We are asked to pause, and immediately notice how ‘Gold’ is placed directly under ‘Heat’; the echo is captured visually on the page, and the break between the possessive ‘your’ and ‘Gold’ makes sense after all.

Strictly speaking, Larkin’s ‘rule’ is unbroken, and since the rule is evident throughout his work it can hardly be termed ‘private’. Moreover, it is observed by many other poets, though some break it with spectacular success. Here is the beginning of Robert Lowell’s ‘ Waking Early Sunday Morning’:

O to break loose, like the chinook

salmon jumping and falling back,

nosing up to the impossible

stone and bone-crushing waterfall –

raw-jawed, weak-fleshed there, stopped by ten

steps of the roaring ladder, and then

to clear the top on the last try,

alive enough to spawn and die.

(Lowell 1967: 13)

Thrice within that stanza Lowell breaks the line between adjective and noun, with exceptional purpose and effect. The breaks – after lines one, three and five – are fundamental first of all to the breaking loose, then to the frustrated progress, the falling back, despite the ongoing energy. When the pattern is broken, line seven ending with a comma, the surge of the stanza subsides, and the end for the salmon is nigh.

Lowell’s brilliantly crafted lines enable the reader to experience, almost physically, the movement of the salmon. We see how the lines work – there is no ‘privacy’ about it – but this paper aims to go further and offer authorial comment of precisely the type that James Tate would avoid. Alongside comment by some well-known poets, and analysis of certain lines, I shall explain my own decisions in forming lines of various types for various purposes.

Enacting the event

The way a line ends is crucial to its character, the defining moment at which a sequence of words becomes a poetic unit, a single entity – irrespective of syntactical connection beyond its borders. The above examples have focused primarily on enjambment, but the Lowell stanza also demonstrates how lines and their breaks are a form of choreography, a dynamic enactment of a poem’s physical (or metaphysical) event.

In the following lines I describe the process of marking out a running track on a school playing field ‘between the Bishop’s Palace and Wolvesey Castle’s ruined walls’:

marked it on paper and transferred it

to grass with pegs and string, then

wheeled the trolley’s dribbling

chalk and limestone mix

along each straight and around each

bend, before crouching to a start

and finally letting the race in my head

move into the muscles of my legs.

(Munden 2017: 26)

For every line break, I wanted there to be a correlation with the physical process described: the transferral from paper to grass; the succession of straights and bends; and the athlete then going over the same ground in the form of a race. There is a deliberate break between the adjective ‘dribbling’ and the ‘chalk and limestone mix’, aiming to capture the trickle of the substance within the wheel of the machine. The positioning of the word ‘start’ at the end of a line is intended to capture the pause, the readiness to begin, while ‘move’ very literally gets the race underway in the final line.

There are, then, detailed correlations between the lines/breaks and the process depicted, which together form a more general correlation between poetic form and its subject – the single sentence unfolding over multiple lines of the poem, just as the athlete’s presence on the track emerges from a sequence of systematic, developing events. Andrew Motion’s poem, ‘The Fish in Australia’ provides a clear example of this general correlation. At a ‘Poetry by Heart’ event in London in March 2014, Motion described his difficulty in writing the poem, the breakthrough coming when he found the natural length of the line, a way of casting it that matched the flicking of the rod:

... hearing how my line

whispered on the water

(now uniformly solid

ancient beaten bronze),

how the reel’s neat click

made the spinner plonk down,

how the ratchet whirred

as I reeled in slow enough

to conjure up the monster

that surely slept below.

(Motion 2014: n.pag)

The poem maintains this casual rhythmic repetition over 79 lines, and the end is noteworthy, the poet continuing to cast out his line,

until such time arrives

as the dark that swallows up

the sky has swallowed me.

(ibid.)

The final line, in isolation, presents an intriguing image, and one that exists only because of the break. If the full phrase were written as a single line (eg as ‘the dark that swallows up the sky has swallowed me’), the effect would be completely lost. The image is the fortuitous result of the poet adhering to the overall ‘casting’ procedure, breaking the syntax in a way that is unlikely to have occurred if the poem had been formed another way, with longer lines.

Is this, perhaps, the best meaning of ‘free verse’ – verse that is free to divine the ideal form for its content, unconstrained by any other considerations? If so, it is anything but free, needing to discover – and make effective – a poetic tactic uniquely matched to its subject matter. Like Motion, I have gone through this struggle. Two very different poems from Chromatic (Munden 2017) provide examples. In ‘Rat Tales’ I felt compelled to work in long chains of miniature stanzas, each of four very short lines, correlating to a key image:

from floor

to rafters—

a heavy chain

of rats, nose

to tail, as if

climbing

the twisted rope

of themselves.

(ibid.: 54)

How easy that might seem, writing such short lines, but each line still needs to work as a unit; the breaks need to be meaningful and there are many times more of them than there would have been in a longer-lined version (‘Rat Tales’ has 164 in total). One-word lines need particular ‘justification’, and put to the test Simon Armitage’s insistence that,

as a minimum requirement a poem should have at least two good ideas per line, for example an unexpected word, a brilliantly executed metaphor, an exquisitely positioned semi-colon, a compelling verb (it’s all about the verbs, folks!) or even a skilfully judged omission i.e. the stuff good poems don’t need to say. (2016: ix)

I would hope that ‘climbing’ does pull its weight as a line: it is a central concept within the poem; its isolation, or rather its place in the spotlight as a unit within the chain, is perhaps the second ‘idea’, in Armitage’s terms. If I were James Tate, I might have coupled ‘climbing the’ and made the break after the article; such a decision would have emphasised the twist; but I am not he.

In the poem ‘Heron Island’ I use lines in an altogether different way – loosely depicting multiple turtles arriving on the beach to make their nests. The poem is in four parts, each of 14 lines, written as part of an experimental sonnet project. Each ‘sonnet’ is characterised by a single (half) rhyme across all fourteen lines, but unlike the other poems mentioned so far, the length of the lines is hugely variable – from two to eighteen syllables. Even with this degree of ‘tolerance’, I take the greater liberty – at the end of the very first line – of breaking a word:

Half-awake, stumb-

ling onto the beach, we almost trip over them:

shadows taking form

as each exhausted loggerheaded limb

hauls its loggerheaded bulk through the gloom

(ibid.: 92)

To break the word for the sake of the rhyme alone would not (for me) have been sufficient; there needed to be the logic of the stumble, the enactment.

Many of the sonnets in Chromatic follow a strict ten-syllable line, though I have never felt any necessity for those syllables to represent any regular beats or number of stresses. As Sylvia Plath states:

I find this form satisfactorily strict [...] and yet is has a speaking illusion of freedom (which the measured stress doesn’t have) as stresses vary freely. (Plath quoted in Muldoon 2006: 47) [1]

Occasionally, as in the (eight-syllable) example below, my ‘lines’ are staggered, in order to expose particular rhymes.

I know

how tinsel must follow

the trail

of candles that thread a soft light

through feathered green

but the whole chain

of bulbs begins to flicker, fail,

and something

falls—a gilded bird.

I try to relocate its perch

but every attempt is just plain<

wrong, and the final effect— search

as I may for another word—

drab. I’m wishing it would come right

[...]

(Munden 2017: 66)

Again, it is not only rhyme that is driving the staggered lines; they correlate with the draping of tinsel on the tree – and the falling ornament.

Elsewhere in Chromatic there are ‘miniature sonnets’, characterised by nine consistently short lines (in two stanzas, the first of five lines, the second of four), and with the title sometimes providing an otherwise ‘missing’ rhyme, as a further forced economy. These short poems came as a natural way of dealing with ideas that I sensed were less expansive, with the line length quickly settling as appropriate to the overall compactness of form.

I have been influenced, in using variable line length, by the sonnets of Paul Muldoon. He is a poet who combines an exceptionally free line with an exquisite fulfilment of form. He says: ‘I don’t scan ... but use a purely intuitive process within each line. My only concern is that the lines are speakable.’ (Muldoon in Haffenden 1981: 141) [2]

His particular use of half-rhyme is distinctive, and it is rhyme that seemingly dictates the increasingly questful direction of his lines. He states:

Rhyme is an element of almost everything we do. There’s scarcely a sound made that’s not echoed. Rhyming is something we hear and see everywhere we listen and look. It’s thought to be something artificial. It’s the most natural thing in the world. You see that hill? Then that one? (Muldoon n.d.)

In contrast to his earlier work, Muldoon’s recent lines can be hugely adventurous, seeming to wander as far as they must in order to find a rhyme – or its pre-echo, aware that they have reached a word with particular magnetic force. Rhyme, then, is sometimes a contributing factor in the stretch of a line, but I turn now to consider lines that have emerged in a very different way.

The sprung rhythm of the psalms

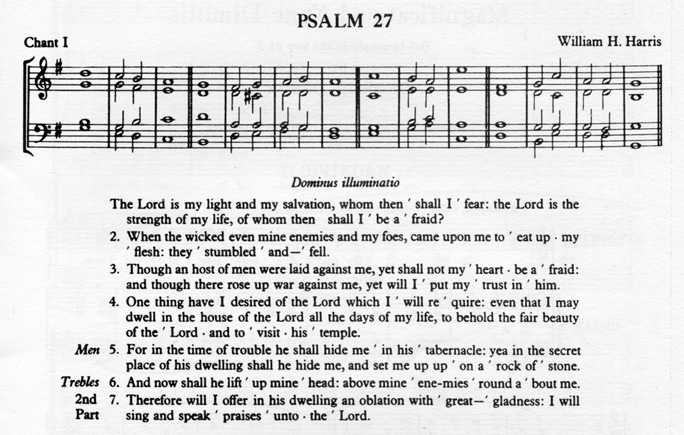

The Bishop’s Palace in my poem quoted earlier is adjacent to Winchester Cathedral, where I sang in the choir and experienced the extraordinary poetry of the psalms sung as Anglican chant. In early 1970s the sub-organist, Clement McWilliam, insisted on exactly what Muldoon says above, that the lines should be ‘speakable’, extending that principle into their musical rendition. Looking at some typical ‘set music’, by William Harris (Figure 1), one sees a succession of chords spread over four sections. In the text beneath, the apostrophes and dots mark the movements from one note to the next.

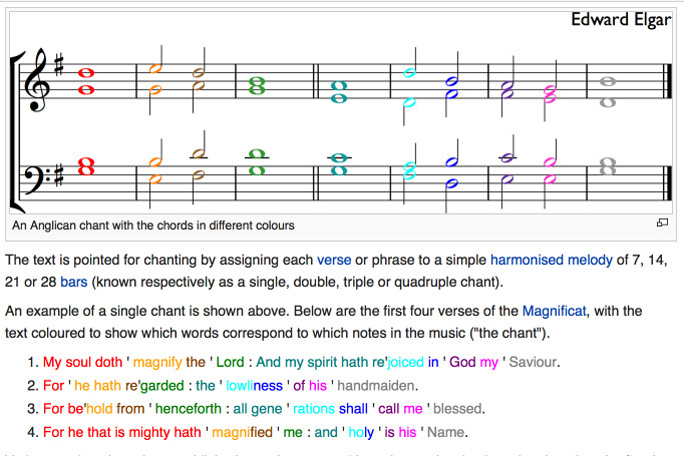

The semibreves (the notes constituting a whole bar) that start each section can accommodate anything from a single word to a long stretch of text; the minims (paired in the bars between) each accommodate only one or two words, leading to the cadence on the concluding semibreve, which this time is matched with a single word. In essence, each bar represents a major stress; where a bar accommodates a longer stretch of text, then yes, there will be sub-stresses, but more delicately inflected than in the metre of poetry as otherwise encountered. To refer to the psalms as ‘unmetrical’ texts, as is commonly done, is inaccurate; it is a different, more spacious type of metre in operation. Each line of the psalm has the same number of major stresses. Figure 2 below uses colour to clearly show the match between musical notes and sections of the text (replacing the dots between words with further colour variation).

The regularity of the major stresses, and indeed the repeating musical chords from one line to another, is offset by an endlessly variable line in terms of its syllabic length and inner inflections. As mentioned, this would seem at odds with conventional poetic metre, but I suggest that its influence on poetic practice (certainly my own) has been considerable, in a variety of ways.

Without discussing such major figures in any depth, I point to Christopher Smart, William Blake, and even Walt Whitman and Dylan Thomas as poets whose lines owe much to the stretch and rhythm of the psalms, the following examples being also of a canticle nature:

Let Simeon rejoice with the Oyster, who hath the life without locomotion.

For Fire is exasperated by the Adversary, who is Death, unto the detriment of man. (Smart 1980: 40)

Let the priests of the Raven of dawn, no longer in deadly black, with hoarse note curse the sons of joy. (Blake 1975: 27)

Let others praise eminent men and hold up peace, I hold up agitation and conflict,

I praise no eminent man, I rebuke to his face the one that was thought most worthy. (Whitman 1938: 219)

All praise of the hawk on fire in hawk-eyed dusk be sung

When his viperish fuse hands looped with flames under the brand [...]

(Thomas 1957: 188)

Smart’s paired lines, sustained throughout Jubilate Agno, are characterised by an ‘antiphonal pattern of versicle (LET) and response (FOR)’ (Williamson 1980: xxii). The second of the two contains one stretch of five unstressed syllables:

x / x x x x x / x x x

exasperated by the Adversary

That corresponds to no recognised metrical foot, but makes perfect rhythmic sense when delivered as ‘psalm’.

It would, I suggest, also make perfect sense to Gerard Manley Hopkins, whose ‘sprung rhythm’ owes much to Anglican chant. Hopkins’s invented term was by his own admission a description of the natural speech form found in earlier poetries (and discussed by Derek Attridge in his various books on poetic rhythm, eg 1995). Hopkins, a favourite ‘poet’s poet’, paves the way both for a revitalised metrical line and the explosion of free verse. In the latter, the regular musical stress of the psalm as articulated through Anglican chant is abandoned in favour of its inclination towards natural speech. The relentless pull, from Wordsworth’s concept of ‘fitting to metrical arrangement a selection of the real language of men’ (1976: 18), to Larkin’s ‘playing off’, is finally complete, only for a whole new art form to exercise an entirely different influence...

Cinematic verse

Ted Hughes’s Gaudete (1977) is a book-length poem that started life as a film scenario during 1962-4, and it is interesting to consider the lines of the poem as visual instructions. Taking some random lines, we see a character, Maud:

She is carrying twigs of apple blossom.

The graveyard is empty.

The paths are like the plan of a squared city.

She comes into the main path.

A woman is walking ahead of her.

Maud follows the woman.

(ibid.: 94)

That simple sequence works perfectly as a shooting script, with close-up (apple-blossom), wide shot (empty graveyard), aerial view (paths like a squared city), and tracking shot (Maud following the other woman). Taking another passage, we see how a wide shot may result in a longer line (as a tracking shot might too); there is more to be encompassed. The close-up that follows it is a single detail, and therefore brief:

Sitting under the farm’s orchard wall, the minister’s blue Austin van,

Blossoms littering it. (ibid.: 47)

The next lines are particularly revealing:

Opening on to the closed yard, a barn-doorway, black.

Estridge is pleased with his telescope

Which brings him a hen flattened under a cock in the barn doorway

(ibid.)

The lines here deliver the filmic instructions in a much more sophisticated, ‘poetic’ way. First we see the yard. We then cut to Estridge with his telescope – a close-up (because there’s no background detail) with him smiling (because he’s ‘pleased’) and he’s looking through it, because his pleasure is directly related to what comes next: a view through the telescope; we know that is the angle because the image of the hen and cock that we are shown is from Estridge’s eye view, brought to him by the telescope.

One further brief extract shows how this cinematographic way of writing can even operate metaphorically:

Curiosity blinks through him. His afternoon

Is adjusted. (ibid.: 107)

We have here something akin to the slow fade; we don’t yet know what next scene will become apparent, but we know that it will emerge from the character’s new thoughts.

Examples of such explicitly cinematographic poetry are relatively rare (and it is interesting that the main Gaudete narrative is not included in Hughes’s Collected Poems (2003) edited by Paul Kegan). In St Kilda’s Parliament, Douglas Dunn offers ‘Valerio’, ‘a poem-film, starring Anthony Quinn’, and ‘La Route’, ‘a poem-film starring Jean-Paul Belmondo’ (1981: 62-70). The second poem offers a very different cinematic experience to that of Hughes. The succession of short lines gives us the breathless jump-cuts of the French nouvelle vague:

This is the speed

We go at: illegible notices,

A gate half-open to a lane

Where . . . Hand on a shutter that’s . . .

Someone’s jumping off a tower

On a chateau that’s blinked by sun.

No. It’s a child who’s throwing

Newspapers out of a window.

(ibid.: 66)

The feel of this is markedly different to Gaudete (not least because of its knowingness), but it shares the sense of the poetic line corresponding to the camera shot, edited with similar ‘grammar’: the cut, dissolve, track and pan, the camera pulling back; the poem as montage. The rhythmic variety of film has surely played a significant role in the development of ‘free’ verse. And there are those, such as Simon Armitage who have written poems purposed as film, or in collaboration with film-makers, for example One Foot In The Past (1993), ‘a ten minute film in verse’ for BBC2. There are also those whose work responds to film, such as Paul Mills’s collection, You Should’ve Seen Us (2011), inspired by the Yorkshire Film Archive. Interestingly, Paul Muldoon (2018) acknowledges his own training as a film director.

Pete Morgan, who collaborated on BBC films, the first of which, Between the Heather and the Sea (1982), is based on his poems written about Robin Hood’s Bay (1983), published a number of poems in his earlier collection (1979) with filmic reference and scenarios. In ‘A scene from Urban Anywhere’, ‘A man is pacing out a park’:

He stops. He strikes a match, the glow

Lights up his face, the fingers show

Some signs of shakiness, unease.

(ibid.: 58)

Each line presents a new ‘showing’, a sequence derived from a highly focused visualisation. The final poem in the collection, ‘The Technicolour Dream’ goes further, incorporating camera instructions:

You, wearing white lawn,

walking – with a light step – LONG SHOT

beside a grey wall. SLOW PAN, LEFT TO RIGHT

At your elbow, a Man. ZOOM

He is incognito.

CUT TO –

(ibid: 60)

Here we see line breaks complemented – or disrupted – by the capitalised ‘screenplay’ text; the poem acknowledges the correlation between poem and film while also problematising it, slowing down the lines’ enactment of the scene in order to highlight the filmic process. In yet another poem, ‘The Television Poem’, Morgan presents a television showroom, where ‘This poem is being transmitted to you’ on multiple screens. Of one of them, he says:

This poem is 625 line.

This poem is 21 inches

across the diagonal.

(ibid.: 10)

It seems pertinent to this paper that a screen should be described here (as indeed a cathode ray tube television screen used to be) in terms of line; the format of screen and poem are analogous.

My own poem, ‘Home Movies’, makes a rather different yet equally direct association of formats. I deliberately took on Geoffrey Hill’s dismissal (at a poetry reading at York University, c1980) of ‘most contemporary poetry’ as consisting of ‘stills from home movies’, using that scathing dismissal as the prompt for a poem that actively and purposefully mimics the things that Hill derides. It begins with ‘the disconnected, wobbly moments / when a camera was at hand’:

A car

is always pulling up and guests pile out.

Thinking about it, they must have

reversed then driven in once more

when we were ready to film.

I’m dressed as Robin Hood – and, OK,

still happy with a feather in my cap

but I wouldn’t be seen dead

in those green tights.

The bow-string slackens

after every shot. I run forward

to pick up my arrow which falls just short

of the target and again, run forward

to pick up the arrow which falls just short.

(Munden 2015: 25)

The lines are attuned to the amateur randomness and wobble of the captured film. Where the poem moves into a specific ‘projection’, it becomes a narrower strip, each line reduced to a minimal ‘frame’. The sense of actuality is intensified, the trope that Hill criticises cranked up a notch.

It’s all there, wound up in my head.

Composition: ‘Holidays’. Now it clicks

through the projector’s gate.

This Easter I packed up

our family house,

sorting the years

of garage junk,

hauling whole suitcases

down to the bonfire.

[...}

(ibid.)

I wish to draw attention to the lines that seem to repeat, the arrow falling just short of the target, not once, but twice. We have surely all witnessed such repeat attempts to capture something, perhaps in our own photography, and the poem’s conceit is therefore easily grasped – whether one is reading it on the page, seeing the second, identical text lining up beneath the first, or hearing the lines delivered. This is an instance of line breaks being registered with equal effect both on and off the page. The more common difference needs some examination.

Sight and Sound

The line break is both a visual and aural force and effect. Poets vary in their oral rendering of line breaks, and our aural appreciation of them therefore varies too. Listening to many readings, it becomes clear that there are two main practices: one is to make a fractional registration of the break, as an additional, almost metaphorical form of punctuation running in counterpoint to its standard accomplice; the other is to ignore the line breaks, which might therefore be considered frauds – or strictly for visual consumption. (There is of course a third practice, where any correlation between line breaks, pauses and punctuation is random, and this tends to be reflected in the inadequate ‘scoring’ of the poem on the page.)

In the visual consumption, it should be acknowledged that there is a fractional pause – a greater length of time moving from one word to the next – that occurs when moving from line to line, than when moving between words within a line. That is of course, to a fractional extent, true of reading prose too, which is part of the reason that prose poems do not entirely escape the concept of lineation (which I will discuss later). There are of course means of addressing this, as readers. Speed reading courses encourage the reading of prose without lateral eye movement, simply scanning down the page. This process is helped by the use of narrow columns of text, as in a newspaper. Poems, often consisting of similarly narrow ‘columns’, might be similarly scanned, but their aim is the opposite: to slow the reader down, considering, even if subconsciously, the entity of each individual line – and the breaks/movements. The white space around the lines (as discussed by Glyn Maxwell in On Poetry (2012)) is a formidable partner in the process; the newspaper column of prose, by contrast, is crowded by further columns.

At a ‘Poetry by Heart’ event for teachers in 2014, Alice Oswald instructed participants to click their fingers between lines in order to register the necessary pulse/pause, later to keep the click silently in their heads. Glyn Maxwell goes further, in helping students to establish the validity of a line break:

Say [the lines] aloud, exaggerate the line-break space – wait longer. If the line-break’s right, something will justify the silence. If it’s wrong then nothing can and the light will snap and you lose the patient. (Maxwell 2016: 93)

Both Oswald and Maxwell clearly champion the first of the practices mentioned above. They demand that the limit of the line is heard – not least to convey the enactment, or indeed the cinematography, discussed earlier. When Heaney writes of ‘the music of what happens’ (1979: 56) he is arguably speaking not only about sound, but also the other dynamics within a poem, including its visual shifts. Viewing the phrase in its full context is revealing:

[...] that moment when the bird sings very close

To the music of what happens.

(ibid.)

In the first line ‘the bird sings very close’ – but to what? – perhaps the poet or the reader; the second line then transforms our perception of what we have just registered. The positioning of the word ‘close’ is masterful; the first phrase is indeed ‘close’ to the second, and not separated by any punctuation; it is nevertheless at a remove. If Maxwell’s test is applied to these lines, they pass with distinction. [3]

Paul Muldoon’s readings offer an interesting variation on this effect, as he tends to slow things down to the extent that ongoing rhythm takes a secondary role to the singular vibrancy of each word as it emerges. This granular delivery accentuates what Maxwell refers to as ‘the babble of close sounds, one word helplessly hatching its neighbour’ (Maxwell 2016: 69). The granular concept, however, also works against the supremacy of the line, which – in the conventional sense – may even disappear.

Consider the so-called ‘word sonnet’, a term coined by Seymour Mayne for his sonnets with lines of only one word (2004). The horizontal lines are reduced to the extent that the vertical composition asserts itself as a ‘line’ of greater meaning. Paul Muldoon includes such a piece within his long sonnet-chain poem, ‘The More a Man Has, the More a Man Wants’ (1983):

Just

throw

him

a

cake

of

Sunlight

soap,

let

him

wash

him-

self

ashore.

(ibid.: 62)

Muldoon has a wonderfully playful reason for his single-word lines, the chain of them acting like a single line of another sort, with which the character can be retrieved. In my own (unpublished) word sonnet, ‘The violinist makes a joke’ (in reference to an in-concert aside from Nigel Kennedy), the playfulness revolves around the concept of time:

Why

do

people

take

an

instant

dislike

to

viola

players

?

It

saves

time.

Kennedy’s verbal delivery of such material is notoriously staccato, a fact that gives further logic to the isolated words.

Hearing these poems read aloud (without any prior ‘explanation’) is unlikely to convey the form on the page; their structure may therefore be considered primarily visual. The same might be said of poems that are right aligned; we may register the line breaks but not their unconventional positioning.

My own first experiment with right-aligned lines was in a poem, ‘Sod’s Law’ (unpublished), where ‘toast falls buttered side / down on the floor’, providing the logic for the lines seeming to fall the ‘wrong’ way. I was then perplexed to see Oliver Reynolds make use of the technique in The Oslo Tram (1991) for reasons I couldn’t fathom. Simon Armitage’s use of the technique in Black Roses (2012) is more transparent: questioned about it at Poetry on the Move 2016, he confirmed that it reflected the fact that the character was speaking from beyond the grave. I now see, though, that in Reynolds’s title poem,

My death

has been timetabled

I run towards it

just as I shall run from it

on rails

As reincarnations go

mine as an oslo tram

will be colourful

[...]

(Reynolds 1991: 7)

My own more recent use of right-alignment has been to create a stereophonic or antiphonal effect, primarily where a poem is simultaneously ‘based’ on two opposite sides of the world, England and Australia (Munden 2015: 70, 71, 93-5; 2017: 66-7, 158-9). In ‘Muldoonery’ (2017: 108-9), the antiphony is between one Muldoon poetry reading and another, again in two different locations, but with the additional, embodied conceit of Muldoon watching someone translate his work into sign language, on the other side of the stage. For me, the more logic there is to a particular tactic, the better its chance of success. The staggered lines of ‘Heron Island’, discussed earlier, are partly constructed as a musical score, articulating the fractional breaks that accompany the rhymes, but they are also pictorial, lines drawn by the turtles crawling across the beach.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to explore the many different ways in which poets have experimented with space on the page and in doing so questioned the supremacy of the line. I will briefly mention just one, since of all my own personal influences, it is e.e. cummings who is most experimental. Born in the 19th century, Cummings began writing formal verse before he made his radical departures from tradition, and the example below shows him all but destroying the line, destroying even the lineation of individual words. The line is atomised; the fragmented text occupies space on the page in an entirely different way. Here he is abiding by nobody’s rules; it is pure adventuring:

?s

tirf lic;k

e rsM-o

:ke(c.

l

i,

m

!

b

[...]

(Cummings 1968: 423)

I’m sure I experimented in an e.e. way, revelling in his particular type of poetic play, but Cummings is Cummings, and even he failed to go further in his radicalism. The above extract is from 1935 and there’s nothing as astonishing in his poems of 1963. Such highly individual invention is not easily imitable with any degree of success; lacking the original creative spark, the imitation slips quickly into parody, and there is something rather sad about witnessing 21st century poets producing pseudo-Cummings poetry, believing it still to be avant-garde. (It would be unfair to point to examples.) I side with Muldoon, who says:

I like the idea that all poems should be avant-garde, yet I find much self-identifying avant-gardeism terribly boring (Muldoon 2013: n.pag.).

Muldoon also says, ‘I’m interested in poems that do things – or attempt to do things – that the best, most well-brought up poems wouldn’t be doing’ (ibid.). In 2018, of course, the catalogue of those well-brought up poems includes Cummings; his effects (and affectations) are manners that the new writer should perhaps treat with healthy disrespect. What one learns most usefully from Cummings is the sheer boldness, and the sense of serious play, invaluable in enthusing young writers, as I can testify.

Too often, though, early encounters with poetry work against such enthusiasm, and it is worth considering here how we are first presented with poetry in school.

Poetry in school, poetry by heart

What models are we given at an early age that either help or hinder our understanding of how we might make poems ourselves? There are typically two: the short-lined, comic, rhyming poem; and the noticeably free, free verse. The first gives a clear model, often enjoyable, but one that is fiendishly difficult for young writers to use for themselves. A prime value of the second lies in its apparent ‘anything goes’ easiness; ‘just move to another line when you’re ready’ (just like James Tate, with no need to justify your process). But is that actually a useful encouragement? Faced with no ‘logic’, no ‘rules’, students often behave like rabbits in headlights: they have freedom to run whichever way they like, and so fail to move; if they do, it’s often in the worst direction. It seems crucial that, to avoid this situation, students are given clear indication of why a poem should consist of lines that stop short of the right margin, working in a different way to prose.

As an experiment, I have introduced in the classroom a poem that conforms to no model I have ever encountered. It is, on first glance, a puzzle, and I’m happy for students to think of it initially in that way. The puzzle is: why have these lines (of prose) been fragmented and arranged in this manner? I include the poem here in full, as I would present it to a class.

Freeze Frame

Plonked in front of the TV

already she’s jabbing h-

ERR!

-emote control in search

of cartoon action or the god-

DAM!

ads. Scary how still she is

though her mind is leapin-

GAH!

-ead. She’s a little editor

at large but the TV’s ca-

UGH!

-t on. Dramas no longer pause

for fear of the audience swi-

TCH!

-ing allegiance. There’ll be

time for reflection, the

BOO!

-k of the series, complete

with inserts on ho-

WAP!

-rogramme is made, for those<

of us who dream of the

POW!

-er to create what we see.

Mum dozes. She’s lost the n-

ARR!

-ative but her daughter

insists there’s a really

GOO!

-d bit at the end, meaning

where the body lands on a sp-

IKE!

(Munden 2015: 35)

The ‘clue’ of course is in the title. And there is, I hope, some fun for students ‘releasing’ the prose from its moments of pause-button hold. The purpose of the puzzlement, however, is in encouraging students to challenge the frequently held accusation that poetry is no more than chopped up prose. It gives them the freedom to accept the accusation, on one level, but recognise too the drama and point of the particular chopping, and move on from there to consider more subtle poetic manoeuvres.

I have found that a sporting analogy is also useful, firstly in encouraging students to realise that poetry can tackle anything, including their own favourite pastimes, secondly in making use of sport’s own grammar. In a game of soccer, there will be short passes and long runs down the wing. It’s a matter of tactics, the use of rhythmic repetition and variety (just as with the film editing concepts previously discussed, and which work equally well a class exercise). Oliver Comins’s collection of golf poems, Battling Against the Odds (2016), is noteworthy here. As the cover information states, it is a ‘collection of poetry about the game of golf and the sport of life’, the golf course featuring ‘a birth, a death, two hauntings, three curses [...] and “a plaintive blues”.’ Golf, then, enables this particular poet to touch on many themes, but the movement of lines remains related to the movements of the game:

a modest drive

is required to carry beyond a deep gully

reaching into the heart of a succinct

and slender fairway. A poorly struck ball

can leap between knobs of stone

before, occasionally, being tossed

just a short chip or long putt away

from the wavering flag. More normally,

you will see its final despairing hop

into the ravine, sacrificed to the tide

or disappearing into camouflage

among like-sized pebbles on the beach below.

(Comins 2016: 19) [4]

Pete Morgan, again, provides another interesting sporting example with his poem ‘The Meat Work Saga’, a boxing poem, where the lines are decidedly light on their feet, and each part (because yes, each round of a boxing match is an identical length) covers a single page and starts and ends with the recognisable procedure. From the beginning, it reads:

My Lords, Ladies, and Gentlemen –

The Meat Work Saga

In the Red Corner In the Blue Corner

weighing in at 168 lbs – weighing in at 168 lbs –

MEAT! MEAT!

1

SECONDS OUT

ROUND ONE

(BELL)

168 lbs of meat

can look good –

168 lbs of meat

can smile –

168 lbs of meat

can dance –

[...]

(Morgan 1973: 39)

The bell sounds again at the bottom of each part/page. Clearly, the overall design of the page is an important part of how the poem plays out. Consider too the repetition. The line ‘168 lbs of meat’ line is repeated 10 times in each part/stanza/round. To begin with, the ‘can ...’ lines are evenly balanced, but then meat ‘throws a shadow’; later it ‘acknowledges its own / existence’ (40),

believes in flags

frontiers

and meat –

(41)

and eventually ‘can dream – / can’t it?’ (42). In the final, fifth round, following the ‘announcement’, there is a blank expanse with just the ‘(BELL)’ at the very bottom of the page (43), as before. The relentless repetition, then, is countered by a relentless inventiveness, distinguished by the ingenious ways in which it varies the formula. If one were to set the task of memorising this poem – another very fruitful exercise in the classroom (see Munden 2015a) – the student is assisted both by the repetition and the variety, as the distinctive changes in pattern, as above, are more easily stored in the memory than a single list of one-liners. Just as William Carlos Williams considers a poem to be ‘a small (or large) machine made of words’ (1969: 256), so Don Paterson remarks that ‘a poem is a little mechanism for remembering itself ‘ (1999: xiv). This elegant concept is of real value in helping new (and indeed established) writers to engineer their work in such a way as to make it memorable.

In ‘The Generation Game’ (2015: 36) I play on this idea of memorisation, presenting what is essentially a simple list poem, framed within a TV game show that requires demonstration of the skill.

Take a careful look at what is passing

before your eyes:

the nest of teak tables

the cut-glass decanter

the snakeskin bag

the snake

the tropical forest

the chalice of spawn

the prime beach, ripe for development

[...]

The poem concludes: ‘You’ve thirty seconds, starting from now: / whatever you remember can be yours.’ The list begins by presenting items exactly as the conveyor belt of consumer goods would in the TV show, but from ‘snakeskin bag’ to ‘snake’ it shifts into new territory. It then moves on to more metaphorical and abstract concepts: ‘the trappings of authority’, ‘the poisoned pen’, and finally ‘the memorial silence / the excuse’. When asked to memorise this poem, students succeed precisely because of the shifts, the variation that is built into the repetition – all within the handy arrangement of lines. Students also find this a model that they can work with creatively themselves.

There must be a brief aside at this point about prose poetry, a form that eschews everything that has been discussed here, eradicating the line in a manner entirely opposite to Cummings’s radical atomisation. Does prose poetry achieve equivalent memorability to lineated poetry of the same length? I suggest not (though colleagues argue vehemently, and it has not been put to any sort of test). Yes, a prose poem might well offer the same shifts as ‘The Meat Work Saga’ or ‘The Generation Game’, but it is the lines and breaks in those poems that are such powerful aides-mémoires.

I have written a couple of poems that I refer to as ‘prose sonnets’. (I thought I was the first to do such a thing, but then discovered Katrina Vandenberg’s prose sonnet, ‘Lost Fabergé Egg I’ (2016), published a whole year before mine.)

My aim was hardly to write a less memorable poem; that would seem perverse. I was however wanting to incorporate certain structural elements of the sonnet, and then relax them, making the machinery less visible in order to gain a particular quality. In ‘The Weathercock’ the iron weathervane is brought down from the roof (of the house where I grew up) to be repainted, and is left to ‘creak this way and that, bereft of the high winds that gave it true direction’ (Munden 2017: 127). The workings of the sonnet are similarly bereft of their usual conditions.

If anything, prose poetry comes with even fewer rules or approved effects than other forms of poetry, and if it aims for a single breathless rush, as a single unit, it actually has no such control. [5] Cassandra Atherton, speaking at the Great Writing conference 2017, referred to her use of single-word sentences as contributing to such breathlessness, but for some readers those sentences may have the opposite effect, slowing them down. Atherton also described her deliberate avoidance of ‘obvious’ line breaks happening on the right margin of the prose poem paragraph, but this again is fraught: the poet makes only a provisional mould into which to cast her prose; a more permanent mould is cast by the typesetter, so the way the lines of prose hit the right margin is likely to be unpredictable; moments that correspond to poetic line breaks may be apparent after all. I wrote a somewhat throw-away piece to exemplify this issue:

if you can’t trust the

future, who can you trust? if you can’t trust the future,

who can you trust? if you can’t trust the future, who

can you trust? if you can’t trust the future, who can

you trust? if you can’t trust the future, who can you

trust? if you can’t trust the future, who can you trust?

Emphasis on particular words changes from line to line, according to placement, regardless of the repetitive syntax. It occurs to me here that a poem such as this might also have value in the classroom, and that prose poetry might be a logical place to start when introducing students to free verse.

Back to the future

Returning to the future is exactly what the accumulating lines of a poem do. They double back on themselves – but into new territory. The lines of Norman McCaig’s poem, ‘Cheerful Pagan’, turns pragmatic imagination into metaphor – and back again:

He’ll cut string with a match flame

and start a car with a paper-clip.

A bed’s head is a gate. He’ll carry water

in his hat.

(McCaig 1985: 315-6)

The ‘gate’ is the entrance to the next invention, the carrying of water in his hat – my italics used here to demonstrate how those words demand their separate line, where they make us marvel at the precariousness of the undertaking. The gate leads on to something that requires a further return to base, in a charming chain of self-replenishing, make-shift behaviour; ‘free’ verse an adventuring with nothing but perfect ingenuity in its backpack.

In a recent poem, ‘Road Closed’, I too go through a gate, using a structure of paired, seven-line stanzas that I have developed over the past two years as a form useful to my purposes. The paired stanzas are staggered on the page, with the result that each pair effects an extra sense of doubling back – to the future.

‘Road Closed’

was emphatic,

but the rusty sign

hung on an open gate,

allowing him to kid himself

and drive on through—

up the narrow sandy track

in an erratic

sequence

of hairpin bends

towards the summit,

and as he continued,

with ever less option

to reverse, he began to forget

the warning, his lapsed

judgement eclipsed

by glimpses of magnificence

beyond—hills, folding

to a pale blue

infinity—

until the sudden, huge stone

fallen into the road.

[...]

(Munden 2018a: n.pag.)

The six-stanza form spreads its rhymes (or half-rhymes) in an erratic pattern, so that they are not always noticeable, but help the meanderings to cohere, and reinforce the logic of the breaks. I have so far written nine poems in this form. I find the flexible short lines, never going too far in search of their rhymes, and the visual sequencing/backtracking effective for my purposes – at this moment in time; in the future a new purpose and therefore a new tactic too will no doubt emerge.

There are those writers, such as Whitman, who may be said to have a ‘typical’ line, but it is perhaps more often the case that writers not only develop, in the general sense, but develop certain types of line for particular purposes. Thomas Hardy, whose line could be so condensed, sometimes lets it run, yearningly, to telling effect, as in ‘Beeny Cliff’:

O the opal and the sapphire of that wandering western sea,

And the woman riding high above with bright hair flapping free —

The woman who I love so, and who loyally loved me.

(Hardy 1974: 46)

By contrast, Seamus Heaney did not start out writing poems with such short lines as characterise North, nor did they remain typical in subsequent books. In that fourth collection, the short lines have the feel of fragments, newly discovered, just like the remains and artefacts being unearthed:

White bone, found

on the grazing:

the rough, porous

language of touch

(1975: 27)

Note that split between adjective and noun again, so tellingly used here to convey porosity.

There is surely a very conscious restraint of line length in North. In other cases, variation or development may be more casual, a ‘decision’ simply to let a line wander as far as it needs, rather than ‘conform’ – either to particular models of prosody or indeed one’s own previous practice. The variety of Paul Muldoon’s line length has grown considerably, from the relative consistency (within individual poems, at least) of his debut, New Weather (1973), to the almost wild variation within more recent poems. In ‘More Geese’ (2010: 13), for instance, he has one line of 19 syllables, one of just three. Similarly, Ted Hughes’s work changes enormously from the formal concision of The Hawk in the Rain (1957) to the expansiveness – some might say sprawl – of River (1983). Outdoing ‘More Geese’, Hughes’s ‘October Salmon’ has one 3-syllable line and another of 21.

Given this degree of variation, is it meaningful to talk of a recognisable poetic voice within the line? Muldoon, for one, resists the very idea, saying: ‘My own view is that every poem is different and needs its own voice’ (2018). One might challenge this, given the exceptional nature of Muldoon’s vocabulary alone. Who else would be ‘micro-tagging Chinook salmon / on the Qu’Appelle / river’ (Muldoon 1987: 9)? Not Robert Lowell, that is for sure. But this raises an interesting point about what we so easily refer to as ‘a line’ from a poem; it is often not a single line as such, but a phrase that might well straddle lines, and this takes us back to the importance of enjambment; the memorable ‘line’ might actually incorporate a break.

But are we necessarily even aware of our ‘rules’ or our intent? Consider Sylvia Plath’s two poems: ‘The Bee meeting’ and ‘The Arrival of the Bee Box’ (1981). The former, characterised by long lines, opens with a question that gives rise to further anxieties – typified by the repetition, ‘my fear, my fear, my fear’, which extends an otherwise short line. The poem ends with the longest line of all: ‘Whose is that long white box in the grove, what have they accomplished, why am I cold.’ It speaks of a mentality altogether unsure about the world and itself. The latter poem, written on the very next day, is entirely different, characterised by short lines and beginning with a statement of authority, a mind in command: ‘I ordered this, this clean wood box’ (212). Even ‘wood’ is pared back from the more obvious ‘wooden’. What this comparison suggests is that, for Plath, the length of line emerges, whether consciously or not, partly as a consequence of psychological equanimity—or its opposite. The second poem’s longest line features the speaker’s moment of self-doubt: ‘if I just undid the locks and stood back and turned into a tree’ (213). The concluding line is again short: ‘The box is only temporary.’ A poem is temporary, too, in that tomorrow may require it to be made anew, with different carpentry. [6]

If rules create formal strength, they also limit, and one person’s rule is the boundary beyond which another breaks new ground. If Lowell had abided by Larkin’s, we would have lost one of the most exhilarating opening stanzas ever written. As writers of new works, we learn both from seeing how personal rules are explained, maintained and developed, and from witnessing how others treat them with creative disregard.

Whither, then, the line in our post-atomic world?

Firstly, there is undoubtedly life in the old dog yet. Even within a poem with largely conventional looks, a line may present a new take on itself. In ‘Fugue #3’, I use a recurring line to represent the alignment of fruits in a slot machine:

[...] the coins from your pocket drop

into the hungry mechanical abyss

plum | plum | plum | plum | banana

—the same old skin on which you slip

each night before time gentlemen is called

(Munden 2017: 14)

The character playing at the machine happens to be the Winchester Cathedral organist; the vertical lines dividing the fruits are therefore perhaps musical bar lines too. And the poem’s end is also its beginning; it works like a möbius strip. The larger line of the poem never stops.

My further faith in the development of the line is not unrelated to that concept of endlessness. The most radical contemporary poetic experiments are online, where lines, like hypertext, may well go in multiple directions – and keep going. (The Wikipedia entry for Digital Poetry is a useful place to start.) The line can no longer be considered to be mono-directional, if indeed it ever was.

This paper is a highly personal assembly of thoughts about the line; it has no doubt glossed over much that others may well consider important. It is nevertheless an open and honest overview of one poet’s thoughts about the line, focusing on personal practice, and taking a stand against James Tate’s maxim. As Derek Neale states, in his crusading introduction to Writing in Practice 4:

we should hear testimonies, investigations, analyses and examinations that divest inspiration of its mystique, while retaining its very real and necessary mystery for the writer. (Neale 2018: n.pag)

Notes

1. Oliver Reynold’s poem, ‘Victoriana’ (1985), offers a virtuoso demonstration of the rhythmic flexibility of syllabic verse. All but a couple of the 168 lines are of eight syllables, and hardly any match in the way they scan.

2. To which one might add, ‘spoken in the right way’. At ‘Poetry on the Move’ 2016 Simon Armitage commented that he practised reading his poems in order to sound like himself.

3. Heaney is quoting from James Stephens’ story of Fionn in Irish Fairy Tales (Stephens 1920), itself a version of an oral narrative.

4. The book itself is pocket sized, in the manner of a golfing ‘yardage’ book carried about on the golf course, and the final page is a scorecard.

5. My own current personal ‘rule’, as applied in recent prose poetry chapbooks (Munden 2017b; 2018) is to accentuate the sense of single unit by having no full stops, only ‘interim’ punctuation, and for the title to operate as the opening words of the poem.

6. My image here is backed up by a comment made about Plath by Hughes: ‘if she couldn’t get a table out of the material. she was quite happy to get a chair, or even a toy.’ (Hughes in Plath 1981: 13)

Armitage, S 1993, One Foot in the Past, BBC2

Armitage, S 2012 Black Roses, Keighley: Pomona Books

Armitage, S 2016 ‘Judge’s report’ in Tremble (ed. N Fanaiyan and M Carroll), Canberra: IPSI

Attridge, D 1995 Poetic Rhythm, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Blake, W 1975 The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Oxford: Oxford University Press/ The Trianon Press

Comins, O 2016 Battling Against the Odds, Matlock: Templar Poetry

Cummings, EE 1968 Complete Poems (2 Vols), London: MacGibbon and Kee

Dunn, D 1981 St Kilda’s Parliament, London: Faber and Faber

Hardy, T 1967 Selected Poems, London: Macmillan

Heaney, S 1975 North, London: Faber and Faber

Heaney, S 1979 Field Work, London: Faber and Faber

Heaney, S 1975 North, London: Faber and Faber

Haffenden, J 1981 Viewpoints: Poets in Conversation with John Haffenden, London: Faber and Faber

Hughes, T 1957 The Hawk in the Rain, London: Faber and Faber

Hughes, T 1977 Gaudete, London: Faber and Faber

Hughes, T 1983 River, London: Faber and Faber

Hughes, T 2003 Collected Poems (ed. P Keegan), London: Faber & Faber

Larkin, P 1974 High Windows, London: Faber and Faber

Lowell, R 1967 Near the Ocean, London: Faber and Faber

MacCaig, N 1985 Collected Poems, London: Chatto and Windus

Maxwell, G 2016 Drinks with Dead Poets: The Autumn Term, London: Oberon Books

Mayne, S 2004 15 word sonnets, Jacket 2, at https://jacket2.org/commentary/seymour-mayne-–-hail-15-word-sonnets (accessed 3 May 2018)

Mills, P 2012 You Should’ve Seen Us, Sheffield: Smith|Doorstop

Morgan, P 1973 The Grey Mare being the Better Steed, London: Secker and Warburg

Morgan, P 1979 The Spring Collection, London: Secker and Warburg

Morgan, P 1982 Between the Heather and the Sea, BBC North

Morgan, P 1983 A Winter Visitor, London: Secker and Warburg

Motion, A 2014 ‘The Fish in Australia’, Poetry by Heart, at http://www.poetrybyheart.org.uk/poems/the-fish-in-australia/ (accessed 3 May 2018)

Muldoon, P 1973 New Weather, London: Faber and Faber

Muldoon, P 1983 Quoof, London: Faber and Faber

Muldoon, P 1987 Meeting the British, London: Faber and Faber

Muldoon, P 2006 The End of the Poem: Oxford lectures on poetry, London, Faber and Faber

Muldoon, P 2010 Maggot, London: Faber and Faber

Muldoon, P 2013 Interview, The White Review, at

http://www.thewhitereview.org/feature/interview-with-paul-muldoon/ (accessed 3 May 2018)

Muldoon, P n.d. Interview with Andy Kuhn, Katona Poetry Series, at

http://katonahpoetry.com/interviews/interview-paul-muldoon/ (accessed 3 May 2018)

Muldoon, P 2018 A Happy Affliction: A Conversation with Paul Muldoon, Los Angeles Review of Books, at

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/a-happy-affliction-a-conversation-with-paul-muldoon/#!

(accessed 3 May 2018)

Munden, P 2015 Analogue/Digital: New and Selected Poems, Sheffield: Smith|Doorstop

Munden, P 2015a ‘Poetry by Heart’ in G Harper (ed.) Creative Writing and Education, Bristol: Multilingual Matters

Munden, P 2017 Chromatic, Crawley, WA: UWA Publishing

Munden, P 2017a Orange, Canberra: IPSI

Munden, P 2018 Rhyme, Canberra: IPSI

Munden, P 2018a, ‘Road Closed’ in States of Poetry ACT – Series Three, Australian Book Review, at

https://www.australianbookreview.com.au/book-reviews/non-fiction/poetry (forthcoming)

Neale, D 2018 Introduction: Critical and creative reflections on process, Writing in Practice, 4

Paterson, D 1999 101 Sonnets, London: Faber and Faber

Phillips, R 2003 The Madness of Art: Interviews with Poets and Writers, New York, NY: Syracuse University Press

Plath, S 1981 Collected Poems, London: Faber and Faber

Reynolds, O 1985 Skevington’s Daughter, London: Faber and Faber

Reynolds, O 1991 The Oslo Tram, London: Faber and Faber

Smart, C 1980 The Poetical Works Volume 1 (ed. K Williamson), Oxford: Oxford University Press

Stephens, J 1920 Irish Fairy Tales, London: Macmillan

Tate, J (n.d.) Good Reads, at

https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/7737767-when-people-start-talking-about-enjambment-and-line-endings-i (accessed 3 May 2018)

Thomas, D 1957 Collected Poems, New York, NY: New Directions

Vandenberg, K 2016 ‘Lost Fabergé Egg I’, The Hampden-Sydney Poetry Review, 42, p41

Williams, WC 1969 Introduction to The Wedge, in Selected Essays of William Carlos Williams, New York, NY: New Directions

Williamson, K (ed.) 1980 ‘Introduction’ in The Poetical Works of Christopher Smart, Volume 1, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Wordsworth, W 1976 ‘Preface’ in Wordsworth and Coleridge Lyrical Ballads, London: MacDonald and Evans (2nd edn)