Keywords: Body mapping — provenance — arts — health — creativity

Introduction

This paper explores body mapping through the lens of general and personal provenance. The word provenance means the place of origin or earliest known history of something. Provenance is ‘a reflective practice tool that scaffolds a practitioner to recognise the elements and experiences that have contributed to their knowledge and acquisition of a practice’ (Hill & Lloyd 2015: 3). Body mapping is a creative tool of inquiry that enables the producer of the body map to explore and articulate their personal or professional story in an embodied and visual way. Body mapping is a way of exploring identity and helps create meaning in relation to life circumstances that shape our lives (Gastaldo, Magalhaes, Carrasco & Davy 2012).

This paper initially responded to the call for papers for a special edition publication of the International Journal for Professional Management, which is based on workshops and presentations from the 2016 Art of Management and Organisation Conference (AoMO) in Bled, Slovenia, and in particular as part of the ‘Making the Intangible Tangible: Stories as a process for organisational and management inquiry’ stream in which I presented ‘Body Maps: Embodied Stories and Artefacts’. It tells the story of my personal encounter and provenance with body maps, and how I have developed body mapping as a creative process of inquiry for others to use from a personal and professional perspective. As part of my ongoing development with this process I have also discovered there is a general provenance to body mapping as a creative visual methodology (Gastaldo et al 2012; de Jager, Tewson, Ludlow & Boydell 2016; Devine 2008). This paper discusses the personal and general provenance of Body Mapping as a creative storytelling process.

Stories as a process of inquiry and meaning-making

Storytelling is a deeply human meaning-making activity. Author and storyteller Geoff Mead (2014) proposes that we live in a sea of stories. Indeed we do; at the core of human communication is the telling of stories. We regularly share and disclose simple and complex stories of joy, sorrow, conflict, uncertainty, love, compassion, anxiety, fear and hope. Often people may not think about their communication in terms of stories. If we do consider how we connect many of us may describe our communication very simply — possibly in terms of talking and listening. At the heart of communication is a desire to have a voice and share meaning. Stories have a long starring role in how we make sense of our lives and the world we inhabit. Oral storytelling is embedded in many cultures, and contemporary culture tells stories through a variety of channels. Technology now enables stories to be shared across many platforms at lightning speed.

I am curious about the nature of stories and how they are communicated. I am particularly interested in the way stories can be revealed through visual artefacts, those objects made by human beings that have the capacity to tell so much without words. We have only to think of some of the magnificent artworks that convey the human condition – Rodin’s The Kiss, Picasso’s Guernica, or iconic images such as Nick Ut’s 1972 photograph of Vietnamese girl Kim Phuc running naked from the napalm attack that disintegrated her clothes – to realise the potency of visual imagery to tell a narrative. These powerful images and stories become etched in our individual and collective minds. Storytelling through the creation of visual imagery is a powerful way to stir emotion, elicit individual experiences and gain new insights (de Jager et al. 2016). It is not surprising that this work is of interest to me: I have a background in design and visual arts, and have spent years making imagery, looking at different types of imagery and, in the past decade, finding ways to use visual imagery in my facilitation and coaching practice.

Over the past few years, one of the ‘artefactual’ processes that has captured my imagination is body mapping. There are two key incidents that led to my experience and exposure to this. The first incident was being thrown into a personal health crisis, in my case undergoing open-heart surgery for a congenital condition; the second was my exposure to body mapping not long after my surgery. The timing of these two events proved to be a perfect storm. First, it became a trigger for my personal exploration and expression of my surgery and recovery. Second, it became the catalyst for my interest in wanting to work with and adapt body maps as a creative tool for working with others.

Body mapping: a personal provenance

Allow me to take you back in time to two major turning points in my life: ‘Did you know that you have a heart murmur? It’s quite significant. You may want to get that checked out’. After various scans, tests and MRIs I am told the news: ‘You have a congenital heart condition that requires surgery — open heart surgery. It needs to be done sooner rather than later.’

I am stunned by this revelation and actually cannot believe what I have heard – it is not what I was expecting to hear. Over time, I come to terms with the fact that I have no other option than to have the surgery and start to plan accordingly. What also begins is an unexpected soulsearching, and questioning of my identity. Pre-surgery anxiety is very real and confronting. I realise I need to find ways to manage my anxiety and so I begin to explore strategies to help me deal with how I am feeling. These strategies include meditation, and creating artworks as a form of art therapy, which I realise at times is a conscious response to what is going on and at other times happens at a more subconscious level. The post-surgery pain, anxiety and grief are also unexpected. I realise I need to continue with my creative coping strategies (Lapum 2005).

So it is a serendipitous and timely invitation I receive during the early days of my recovery from a group of creative management and academic colleagues based in the UK to join them, virtually, for their yearly professional development gathering. I am grateful they asked me, as I have great respect for their artful methodologies in relation to working with the personal within organisational life. I appreciate the opportunity to engage at this level during my recovery from surgery, as I have felt isolated and vulnerable. I have not been working professionally, and my confidence generally has taken a battering.

From the other side of the world — me in Australia, and the others in the UK — I am beamed in to witness and hear the stories of what they have been working on. It’s approximately three months after my surgery and my colleagues at that moment are unaware that I have been through open-heart surgery. We talk for a while, and then I am transported around their working space via a laptop, and exposed to a series of life-size drawings and collaged figures that this group has been working on. Even via technology and distance the images that appear on screen of these large-scale portraits has quite a profound effect on me.

Over time, I have tried to understand the initial impact these artworks had on me. On reflection there are a few factors that I think influenced my intense visceral response. The scale alone was striking; the aesthetics thought-provoking, beautiful and raw; there was detail and creativity; and I sensed a heartfelt engagement from everyone in terms of undergoing a process of self-inquiry. The body maps (as I coined them) revealed to me stories of the human condition — each unique, and yet somehow the same. As they showed me their artefacts they also told stories to accompany them – again they were deeply thoughtful and reflective, just like the artwork itself.

As the conversation unfolded, I felt a deep sense of emotion and began to cry. These large artefacts spoke to me, and I knew I needed to respond. As I shared my feelings with the group I revealed what had recently happened to me regarding my heart surgery. They were taken aback and moved. The discussion then flowed, and the general response was that the sharing of my experience had an impact on their perception of their maps, and had seemed to deepen everyone’s appreciation of their experience.

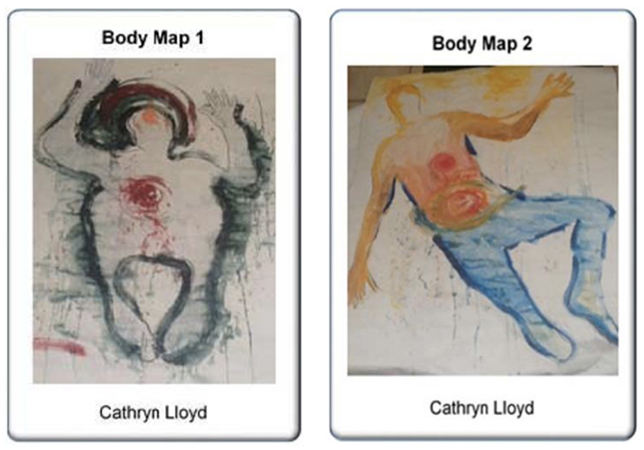

After that virtual gathering, I am compelled to produce my own visual artefact and I make my first ‘body map’. As part of the process I ask my husband to draw the outline of my body. The conception of my body map is completely intuitive, immediate and expressive. What lands on the page is a completely somatic response, with no editing: a pouring out of feeling and emotion. When I step back from the paper, I am revealed to myself. It shows me in a curled and hunched-up position. It embodies how I feel – hunched, constricted, inward, and not at all happy. The colours I have used are dark and heavy — black, red, dark bottle green, and a big red swirl in the middle of my chest. A dark halo hovers above my head. The image depicts so much of what I have been feeling over the past few weeks. Wounded, raw, in pain a casualty of what has felt like a brutal assault. What is presented to me is quite confronting. I stare at the image and wonder if I will ever be me again. I send the image to my UK colleagues, who respond with respect and further appreciation of the deepening of their understanding of the process.

About three months later, I have the urge to create another body map. This one is more open, spacious, lighter and brighter. The colour yellow features strongly and there is a vibrant orangey/red swirl over my solar plexus. I am beginning to feel more energized, and the image shows aspects of that. I am beginning to look out into the world, to emerge; I’m not so stuck and contained within myself. Slowly I am beginning to feel more at peace, the pain is lessening. I am feeling more hopeful, less vulnerable and exposed. One day I will feel normal again … one day … the image tells me that.

When I compare both body maps they reveal the different stages of the journey I went through from the early post-surgery days and further into recovery. The colours and body shapes in my maps tell their own stories. Doing the body maps was a profound experience that allowed me to experience and explore, beyond words, a significant turning point that I know has shaped my life. Along with a physical reshaping of my body there has been a psychological reshaping. The entire experience is somehow captured in the words of artist Georges Braque, who is quoted as saying, ‘art is a wound that becomes light’.

What became clear to me through the intense effect the body maps had on me was an overwhelming sense that I wanted to work with others using this process. My gut feeling at the time was that they could be a valuable and creative way for people to engage in a personal or professional exploration of critical events and turning points in their lives that may have shaped their identity. The flip side of my conversion was my concern that their resonance would not be the same for others. That maybe the body mapping impacted on me because of my particular experience, and others would dismiss the process and not see the value in it.

Another reason I think the body maps spoke to me is my background: first in the arts, and now in facilitation and coaching. It seemed to be a natural progression for how I might be able to work artfully with others in terms of self-inquiry and reflecting on critical experiences. Although I had reservations I decided that the only way I would know if body mapping could be a useful tool for artful inquiry would be to start working with others (Lloyd 2011); and so began the journey of how I might go about that.

Body mapping – general provenance

While I have a personal ‘provenance’ (Hill & Lloyd 2015) of body mapping through producing, writing and presenting about body mapping, my inquiry reveals there is also a history, a general provenance to this process. There are others who have used body mapping in other contexts and for different purposes. Body maps have been used as an arts-based research method and for therapeutic interventions in areas such as health, safety, educational and community development. In ‘Embodied Ways of Storying the Self’ (2016), de Jager, Tewson, Ludlow and Boydell undergo a systematic review of body mapping and identify various implementations of body mapping in research, therapeutic and educational contexts.

Body mapping as a technique has been used for clinical purposes, and the first instance of body mapping was recorded in 1987 in a research study to compare high fertility rates in rural Jamaica and the UK (de Jager et al 2016). Body mapping was also used as an advocacy tool to bring attention to the issue of HIV/AIDS in Africa, and rapidly became a tool for storytelling, helping women with HIV/AIDS to sketch, paint, and put their journeys into words (Devine 2008; CATIE n.d.). In another context, Dr Katherine Boydell from the Black Dog Institute reflects on how she and her colleagues are starting to use body maps to map anxiety and issues around mental health. They are keen to see body mapping develop and become ‘an acceptable form of data and qualitative research tool’ (in Hoh 2016). In ‘Body mapping storytelling’, researchers Gastaldo, Magalhaes, Carrasco and Davy (2012) use body mapping to tell the complex stories of the lives of ‘undocumented migrant workers’ in Canada. The authors adapted body mapping from a group therapy model for its application as a research method for their study, and they see body mapping storytelling as a biographical tool that can be used to show and tell people’s life stories.

Body mapping—a process

Research shows that body mapping has been used in a range of contexts and for a range of purposes, and also reveals similarities and differences in how the body mapping process is used and facilitated. There are some core characteristics to be considered. For instance, the scale of the body map – should it be life-size, can it be smaller, or larger than life? Another consideration is the purpose, and to question the how and why of body mapping (de Jager et al 2016). Is it being used as research methodology to collect data, or is it purely as a creative tool for self-inquiry; and what about ethical considerations?

In this paper, I explain the way in which I have used body mapping as a process for working with others. The premise from which I work is that body mapping is a storytelling and inquiry process that enables people to reflect on personal and professional life experiences through the creation/production of a visually rich picture or artefact — a body map — to gain a different perspective or insights which may influence what they do now or in the future.

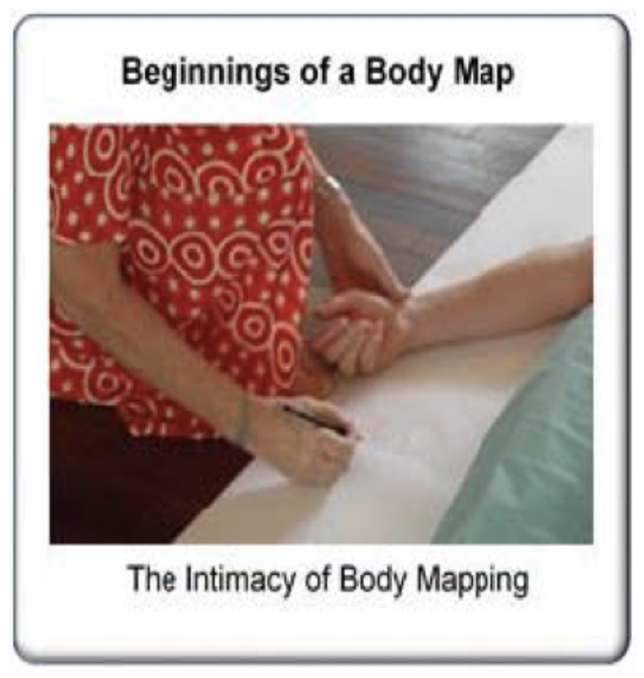

In workshops, I begin the process with the ‘body mapper’ having their bodies drawn (by another person) as a lifesize outline drawing in a pose they have chosen. The outline can be as detailed or as simple as the body mapper decides, and they in turn instruct the person who is drawing them. As a facilitator coach, I am aware I have a responsibility to help set the scene for the body mapping process, and I am conscious about how much direction and input I offer, and where I stand back to allow each person to find their own way. This is where the art of facilitation makes itself known; it involves sensing and feeling into the group experience as well as working individually with participants. There are choices I make in relation to the questions I may communicate to the entire group and then how I may engage with individuals. For instance, at the beginning of the process some of these questions are focused on the group and quite specific such as:

Consider what you would like your outline shape to look like; this might be based on a present feeling or situation or it could be future focused — what or how would you like to see of yourself in that initial drawing outline?

Another aspect to be aware of is that the drawing of another person can be perceived as intimate, and therefore requires sensitivity and respect. Not everyone is necessarily comfortable working so intimately with another person, particularly a stranger.

Some of the initial questioning is meant to trigger an internal conversation as to how the person may currently see themselves; or it may be future-focused and more about how they would like to see themselves. The body outline becomes the starting point for a visual and textual self-inquiry. Part of the initial questioning and kindling is to encourage people to focus on whether there is a particular story, incident or angle they have identified, and feel there is value in further exploration.

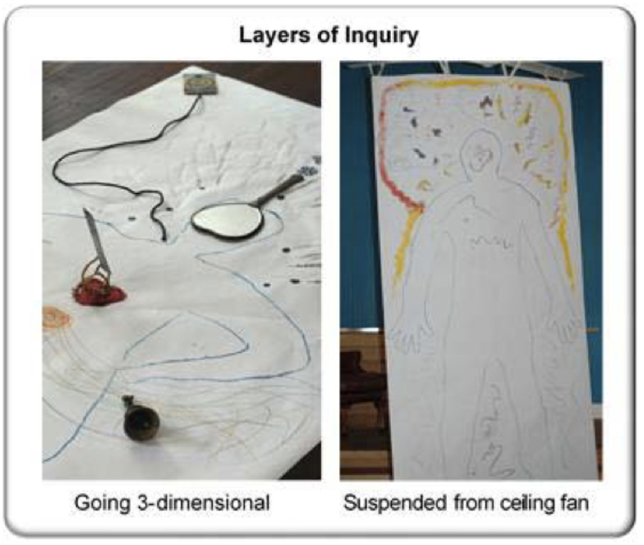

As the process unfolds and people work on their body maps, that line of inquiry may continue, and deepen or shift as the artefact emerges and makes itself known. There are also aesthetic decisions to be made. What emerges is often a combination of the conscious choices and decisions people make during the process, as well as responses to the emergent image. This might be in the colour choices, in the particular materials used, or whether they stay in one-dimensional mode or move it into a three-dimensional image. For instance, they may add objects that are significant in shaping the inquiry and providing granularity to the image and story; they may hang the body map from the ceiling as a way of articulating facets of an unfolding story as depicted in the images. These are either deliberate or emergent choices people make as they engage in a reflective inquiry as revealed in the two images, Layers of Inquiry.

As Gastaldo et al point out, Body-Map Storytelling reflects individuals’ embodied experiences and meanings, attributed to their life circumstances, that shape who they become (2012: 10). People’s lives are a rich tapestry, and when exposed to the body mapping process a person may see and work with the multiple stories that make up their life, or they may focus on a particular story they think would be worthwhile to explore in more detail. What I have often noticed during the process is the emergence of stories that have been hidden from view.

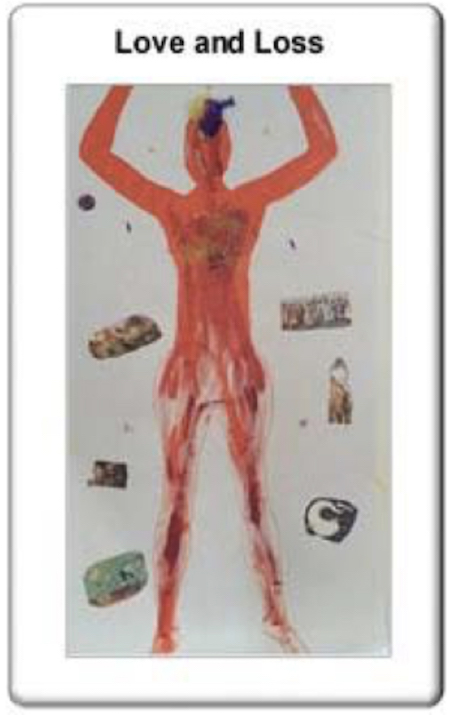

The process therefore provides the opportunity to explore an obvious primary narrative or a subtle partially formed story waiting to be noticed and brought to life. For instance, the body map Love and Loss emerged from a story about love, the grief felt from the loss of a parent at a young age, and a realisation that too often, for this person, decisions are made based on time and schedule rather than from the heart. Later the person who created this shared with me that in the lead-up to body mapping they experienced some anxiety about the process of making the body map, and at one point considered finding an excuse to leave the workshop. Fortunately they stayed, and found the process worthwhile from a personal and professional perspective.

Body mapping can enable people to generate new stories of becoming. The body mapping process is not static; it is experimental, dynamic and playful. The process allows stories to emerge, retreat, and be reworked. Body mapping becomes a tool of articulation (Lloyd & Hill 2013) — a creative visual tool that offers a visual language for people to reflect on and reframe their story. Body mappers can imagineer a metaphorical artefact (Lloyd & Hill 2013; Gauntlett & Holzwarth 2016) that may be based on past, present and future stories. This spirited process is a story not only of becoming but also of arrival.

In the workshops, body maps are drawn on large pieces of paper, generally on the floor — at least at the start. If people have problems working on the floor for a long period of time, tables need to be supplied. An alternative approach would be to attach the paper to the wall and work from a standing position, which does happen at various stages as people start to refine their body maps and have a desire to view them from a different perspective. Body mapping can employ a range of materials and artful making, including drawing, painting, found images, collage, symbols, three-dimensional artefacts, poetry, key words, basic mark-making and metaphors as some of the key elements. I encourage people to play and experiment with creating their own symbols and images rather than relying on too many pre-existing commercial images.

This aspect of body mapping can be challenging for people — often in terms of an individual’s perception about their creativity and artistic ability — but it does provide an avenue for a unique, idiosyncratic and personalised body map. Pre-existing images can be useful, and provide starting points for people and stimulate ideas. For instance in one workshop, as part of the preliminary work prior to the body mapping process, participants selected a couple of commercial images to start a discussion about where they felt they were currently, in their professional capacity. One of the participants selected an image of a pair of ballet shoes and spoke about the influence of performance and dance in their early life, and how they didn’t dance any more. This illuminated for them that they needed more creativity in their life, and how their current professional life was not providing that. The ballet shoes image influenced their approach to their body map, and in the process they created a portrait of themselves as a dancer. The body map became a dancing metaphor – a reminder of what was missing and was needed. It became a stimulus for action in terms of making changes to their work situation.

As part of the process, I encourage people to take photographs of the body mapping in progress. This allows the individual to follow the development of their body map story. The process of recording stages allows people to return and see the points at which change has occurred and where they have made certain choices. This provides opportunities for further reflection and questioning. For example, from various change points in the body map we can ask, why did I make that change. What was I thinking when I chose to position myself in such a way? What is it about that the colours, symbols and icons that are significant? Each time a conscious reflection is made it has the potential to inform the future development of the body map and potentially influence future personal or professional choices.

I have a preference for building or integrating the body mapping process into a bigger creative learning scope, such as a full day workshop, or part of a longer-term programme. From my experience people often find the process challenging and at times somewhat confronting. Sometimes this is linked to feelings about their creative ability such as ‘I don’t make art’, ‘I can’t draw’ ‘I’m not creative’, and ‘I don’t know how to use art materials’. It can also trigger personal commentary about their bodies. So it is important to spend time building relationships, particularly in a group setting. Spending time with other creative methods as part of warming up to the body mapping encourages conversation, movement, and reflection, and offers a more holistic journey toward the body map rather than crashing into it.

Body mapping requires time — it is not something that should necessarily be rushed. It often takes people a while to get a feel for what the process is about, and what they are going to do. Settling in to body mapping is part of the process. It is sometimes met with some resistance or anxiety as people grapple with assumptions or commentary around their creativity and in how they perceive the process. The time required will depend on how much time I have with those I am working with. At a minimum my preference is for a full day or two half days in which we journey toward the body mapping process. At a minimum I set aside three to four hours for the process itself, although it can take longer. I encourage more time rather than less to allow for a deeper inquiry. This includes time for reflection and, if people are willing to have a discussion about their body maps, the process itself, and what insights they have gained. Not everyone is comfortable in sharing, and in one situation a body mapper did not want to discuss the body map as they felt they would be judged. But on the whole I find people do want to share, and are very interested in hearing their fellow Body Mapper stories. It is a bonus if people can return to their maps at a later time, such as the next day or over the following week. This allows for incubation and to see what emerges when people have had time to process and reflect. One person who has been through the body mapping process a couple of times said:

The body map is very different this time. I had to consciously move away from what I did before. I wanted to create something different. It’s created a shift and that’s the lived experience of doing something rather than talking about. In the doing we transform … so if this is action-based learning it is happening in the moment and we are transforming as we do it. We are becoming the embodiment of the change.

How people respond to body maps

Over the past three years, I have delivered workshops that invite people to delve into their personal and professional lives by working with a range of creative methods, which also includes body mapping. From my observation and the discussions that unfold once people have created their body maps, it seems most people have quite a visceral and meaningful response to their maps. It is not always an immediately positive engagement: for some it can be challenging and confronting.

Sometimes people rush into making quick judgments about the process; for instance: ‘I had to suspend judgment, cynicism. I had to allow myself, give myself over to the process and to play. I felt exposed. We’ve been trained to distance ourselves’. For others the process can be liberating, as one person explained: ‘It was far more practical, kinaesthetic and immediate which helped bring me into the present moment. I warmed up to it and began to feel free and liberated — there was a level of trust that had built with the group’. For others again, it provides further insight into how they currently see themselves, as well as realising there are other ways to navigate their life. As one person shared:

There is a richness and depth in the pictures. It shows things that often can’t be verbalised. The imagery in my body map is powerful … there is stuff around the heart and the head. It’s not natural for me to keep my heart open. I have to work at it although I know I am sensitive, I need to protect myself. It taps into other ways of knowing, creating images of sensations making connection to the parts of the body that have different knowledge.

With any intervention one needs to be mindful about how a creative process like body mapping is used. There are ethical considerations involved in using any process of reflection and inquiry that asks people to reveal personal and professional stories. It needs to be undertaken with great care, transparency and with the goal of helping people understand the purpose and potential benefits as well as deal with concerns. Ideally these sorts of professional development processes are done with participants who are willing and see the value in undertaking such a process. If an environment of trust, psychological safety and the benefits of an artful inquiry (Lloyd 2011) within an organisational context are understood there is the possibility of deepening connections and relationships, and bringing our humanity into professional life. Creating space for people to explore and flex their personal and professional identities provides a way for participants to see the depth and creativity of their colleagues.

Body mapping is an aesthetic and artful inquiry that provides a way for people to reflect creatively on their practice and in the process generate theories for and about themselves (Gauntlett & Holzwarth 2006). Individually and collectively inquiring into current professional identities, and experimenting and playing with future professional identities can provide new perspectives and insights on how people see themselves and others professionally. When fully explored, body mapping involves the head, heart and body, and is a creative process for professionals to make tangible the intangible aspects of professional life.

At the 2010 AoMO conference, I presented my body mapping story, and took delegates on a very brief spoken journey, similar to what is reflected in this paper. I was keen for delegates to have an experience of the process, albeit a very brief one. As a simple gesture I invited conference delegates to draw a part of their body, as a taste of what is involved in producing a body map. This was well received in terms of moving people from hearing a theory and process, to putting it into practice. It also provided delegates with the opportunity to consider how they might work with body maps.

Body mapping for organisational and management inquiry

Body mapping is an embodied, creative and humanistic process to explore human territory and to share those stories. There are times when we need another language beyond words to describe what our life experiences mean. As Gastaldo et al explain in their research about undocumented migrant workers, Body Mapping was used to:

engage participants in a critical examination of the meaning of their unique experiences, which could not simply be achieved through talking; drawing symbols and selecting images helped them tell a story and at the same time challenged them to search for meanings that represented who they had become through the migration process. (2012: 8)

This is potent work that can be used in different contexts, including organisational life. I have worked with a couple of organisational groups in the corporate and not-for-profit sectors. In both situations I used body mapping within the framework of a one-day professional development workshop. Feedback from both groups was positive in terms of being given the space and time to individually reflect on and explore their professional life and to help create a shift in their thinking. For instance, people commented:

‘It’s great to have the time to reframe and think in a different space not about the business but about ourselves.’

‘Creativity needs energy and we need to allow ourselves to be energised.’

‘I saw more in the body map of myself than I have seen for some time.’

They also commented favourably on body mapping as a collective process with their colleagues, which they believe provided an avenue to get to know one another in a ‘different way’. As one person said, ‘It was worthwhile using different mediums to engage the senior management team in understanding and appreciating our differences.’

Most seemed to think there was value in doing this type of creative reflective work on a regular basis to re-invigorate themselves and build relationships with their colleagues. As one person offered: ‘I’m big on team building and so I will continue to implement creative team-building activities for all staff to continue to create effective working relationships.’

Within an organisational context there are potential benefits to undergoing professional self-inquiry, at both an individual and collective level. There are times when the complexity and challenges of professional life can be difficult to articulate clearly in words (Caza & Creary 2016). Making the intangible aspects of professional life tangible can help generate new insights and understanding in terms of one’s own practice and that of others. As the world becomes more complex, and organisational life becomes more multifaceted, the ability and courage to reflect on how one experiences professional life becomes critical (Caza & Creary 2016). Never has this been more needed, in terms of leadership and management (De Courtere & Magellan Horth 2016). Equally, as concepts such as creativity and innovation are emphasised as key drivers for organisational success, creative professional development, self-awareness and insight become crucial. As organisations experience uncertainty there is increasing demand for people to be more flexible and adroit in thinking and behaviour (Caza & Creary 2016). That does not happen easily in organisational life if the culture is one of business as usual. People and organisations can stagnate, and we have seen many institutions disappear or get taken over by more agile competitors.

With any intervention one needs to be mindful about how a creative process like body mapping is used. There are ethical considerations involved in using any process of reflection and inquiry that asks people to reveal personal and professional stories in the workplace. It needs to be undertaken with great care, transparency and with the goal of helping people understand the purpose and potential benefits as well as deal with concerns. Ideally these sorts of professional development processes are done with participants who are willing and see the value in undertaking such a process.

If an environment of trust, psychological safety and the benefits of an artful inquiry (Lloyd 2011) within an organisational context are understood there is the possibility of deepening connections and relationships, and bringing our humanity into professional life. Creating space for people to explore and flex their personal and professional identities provides a way for participants to see the depth and creativity of themselves and their colleagues.

Body mapping is an aesthetic and artful inquiry that provides a way for people to reflect creatively on their practice and in the process generate theories for and about themselves (Gauntlett & Holzwarth 2006). Individually and collectively inquiring into current professional identities, and experimenting and playing with future professional identities can provide new perspectives and insights on how people see themselves and others professionally. When fully explored, body mapping involves the head, heart and body, and is a creative process for professionals to make tangible the intangible aspects of professional life.

Acknowledgments

This paper was originally published in the 2017 Special Edition: Arts and Management, of the International Journal of Professional Management 12.3: 42–54. Axon is pleased to republish it, slightly amended, and give it a new audience that includes artists, art practitioners and community arts workers. Cathryn would like to acknowledge those who have attended her workshops and kindly let her use their images.

CATIE (n.d.) ‘Body maps: Women navigating the positive experience in Africa and Canada’, http://www.catie.ca/en/bodymaps/bodymaps-gallery#learn (accessed 18 February 2017)

Caza, BB & SJ Creary 2016 ‘The construction of professional identity’, in A Wilkinson, D Hislop & C Coupland (eds), Perspectives on contemporary professional work: Challenges and experiences, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 259–85

De Courtere, B, & D Magellan Horth 2016 ‘Innovation leadership’, Centre for Creative Leadership Training Journal, https://www.ccl.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/center-for-creative-leadership-training-journal-innovation-leadership-article.pdf (accessed 18 February 2017)

de Jager, A, A Tewson, B Ludlow and MK Boydell 2016 ‘Embodied ways of storying the self: A systematic review of body-mapping’, Forum qualitative social research 17.2 (Art): 22

Devine, C 2008 ‘The moon, the stars and a scar: Body mapping stories of women living with HIV AIDS’, Border crossings, http://www.catie.ca/pdf/bodymaps/BC_105_BodyMapping.pdf (accessed 18 February 2017)

Gastaldo, D, L Magalhaes, C Carrasco and C Davy 2012 ‘Body-map storytelling as research: Methodological considerations for telling the stories of undocumented workers through body mapping’, http://www.migrationhealth.ca/undocumented-workers-ontario/body-mapping (accessed 13 July 2016)

Gauntlett, D and P Holzwarth 2006 ‘Creative and visual methods for exploring identities’, Visual studies 21.1: 82–91, DOI: 10.1080/14725860600613261

Hill G, and C Lloyd 2015 ‘A practice-led inquiry into the use of still images as a tool for reflective practice and organisational inquiry’, International journal of professional management 10.2: 1–15

Hoh, Amanda 2016 ‘Science week: Body mapping anxiety with life-sized artworks’, ABC Radio Sydney, 11 August, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-08-11/body-mapping-anxiety-for-science-week/7715996 (accessed 13 February 2017)

Lapum, J 2005 ‘Women’s experiences of heart surgery recovery: A poetical dissemination’, Canadian journal of cardiovascular nursing 15.3

Lloyd, C 2011 Artful inquiry: An arts-based facilitation approach for individual and organisational learning and development, Professional Doctorate thesis, Queensland University of Technology

Lloyd, C, and G Hill 2013 ‘Human sculpture: A creative and reflective learning tool for groups and organisations’, International journal of professional management 8.5 (September): 1–10

Mead, Geoff 2014 Telling the story: The heart and soul of successful leadership, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass