Keywords: Joshua Yeldham — artist — creativity — residency — spirituality — family

Introduction

This interview with Sydney-based painter and visual artist Joshua Yeldham took place on 2 August 2017 at Tweed Regional Gallery, Murwillumbah NSW, days before the opening of his new exhibition Endurance. This exhibition showcased works that Yeldham created during a special residency at the gallery in February 2017. Yeldham, also an Emmy-winning filmmaker and the author of one book, Surrender: A journal for my daughter (Colo River 2014; Picador 2016), works with various materials and experimental techniques to create his large-scale artworks that he has been exhibiting for the best part of twenty years.

The conversation began with our discussing the nature of such residencies: what they are like from day to day, what his intentions were prior to arriving, and the impact of the surrounding landscape on how he approached the new work. This expanded to questions of creativity and spirituality, which Yeldham believes are inherently intertwined, and his personal relationship with the natural world. From this we discussed the nature of family, fatherhood and femininity in relation to creativity and making art.

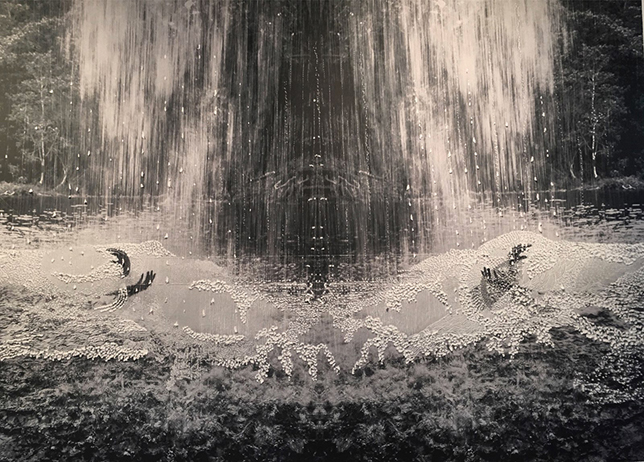

We are seated directly underneath a painting entitled ‘Two Hands — Killen Falls’, which was inspired by a frightening incident Yeldham and his family witnessed while on holiday in New Zealand. Visiting a popular waterhole at Mount Aspiring National Park, he saw a man nearly drown after leaping into the freezing water, having been egged on by his friends. This man, whose body went into shock from cold, descended fully clothed to the bottom of the pool, where he stayed for several minutes before two young Englishmen were able to rescue him and he was revived. A trip to Northern Rivers beauty spot Killen Falls during the Tweed residency revived the memory, and this led to the finished piece.

Barnaby Smith: The painting ‘Two Hands — Killen Falls’ has a rather dramatic backstory doesn’t it? What happened in New Zealand?

Joshua Yeldham: The man was under water and didn’t come up, but the water was numbingly cold, so my judgment was not to go in, but to run for medical help. There were about thirty of us watching this, including his mates, and he was so big and strong that when he was fighting in the water a mate went near him and then backed off because he was going to take him down — he was grabbing, in fight or flight mode.

After he’d been down for about two minutes, I ran for help, and then Jo my wife said, ‘Can anyone strong go in there?’ and these two twenty-year-olds, lifeguards from England, stripped to their shorts and dived in. They grabbed his jacket and pulled him somehow to the pebble beach, where my wife and two doctors happened to be, and they brought him back. And when I got back from running to get a phone signal, he was like a wild animal, in full delirium. He finally came round to full consciousness and he wanted to know who saved him, who rescued him, and he kept saying thank you.

He was a very overweight Muslim man who didn’t have swimming skills; the other men were praying to Allah and in shock. Everyone was in shock, my children were screaming and upset so I had to get them out of the way, and then a chopper came and carried him away. Many people acted. My problem, which I faced for about three days afterwards, was about me not going in the water, because normally that’s who I am, but this time I didn’t. I held my own value and didn’t want to risk it. And that space created these artworks.

The beautiful part at the time was that everyone worked perfectly in their own capability and that these two other candidates, who were picked to swim, were far fitter than me. I have to respect the sequence, and my point in the sequence now is to tell the story and make the art. A different sequence and I’d be in the water. But I’ve grown from it, everyone’s grown from it. That’s all we can ask for.

Barnaby: Your residency up here occurred in February 2017. What were your intentions ahead of the residency, and what artistic questions were on your mind?

Joshua: Learning country in detail. On the first day I drove up to Mount Warning, feeling that out, feeling out where I was comfortable. I really felt comfortable in the mangroves at Brunswick Heads, and at Fingal Head, which was very powerful, very charged, with the pandanus trees and the water holes. You go on a bit of a road trip and things start to occur, and having the residency allows you to stay here economically and I could make a mess, whereas if you’re staying at a friend’s house you can’t really rip the place up and make a mess.

The main element is to be aligned with this gallery space. I got to sit in this space, and slowly I was curating it. I loved the experience. With commercial galleries you’re working with the curator; with this I’ve been given the freedom to design it.

Barnaby: What were your initial impressions of the Northern Rivers landscape?

Joshua: Abundance and vigour. The vigour and the rigour of nature, how it is omnipresent and so vital that people have to work overtime to keep nature at bay from their doorsteps. Particularly in Nashua [where Yeldham stayed with friends for some of the residency], which is macadamia country with vines and soil that are so rich and strong, humans are very much guests. You don’t have that feeling everywhere now, thanks to mass development.

Nature is the overwhelming force and, as a storyteller, it’s very powerful for me to be aligned with it. It was also pre-flood so it was very dry, and I didn’t have that storyline; the flood occurred when I was back in the studio in Sydney making these works, so I had a great appreciation that, at the drop of a hat, alignment can change and chaos shoot through.

Barnaby: How aware were you of the catastrophic floods in Murwillumbah [April 2017], and did it have an impact on the final works?

Joshua: I kept phoning up and learning the moving story of how the gallery became a refuge, how caravans ended up parking underneath. Homes had to be evacuated and people lived in the carpark. The artist who had a residency after me, Fiona Lowry, had a very different experience from mine — she had to deal with a hundred people camping here. She’s got quite an amazing story to tell.

Barnaby: How did you arrive at ‘Endurance’ as the title of the exhibition that came out of the residency?

Joshua: One day I rolled my papers up and took them out with me on a canoe. I spent the day next to a mangrove in Brunswick Heads, in one of the estuaries. I didn’t see a single human, and I had the privilege of staying longer in nature than most humans can, because I had a purpose. The minute you give yourself that reasoning of why you should stay longer, after the first layer of intelligence says, ‘Okay, I’ve kind of had enough here’, you’re allowed to stay longer and longer in nature. I wanted to align myself to that one tree, that mangrove, with my brush and my ink, and I had endurance. Hence the name of the show: to last longer, to feel connected to that moment. And that gives me a joy that is more stable than any other I know of.

Barnaby: While that sounds like a somewhat meditative experience, it also sounds like a degree of focussed hard work is required to respond to nature in the way you describe.

Joshua: It wasn’t only about making work that’s going to be in a gallery space. It was about me saying ‘There’s something charming about this bank, I’ll stop my canoe here, I’ll stay awhile. I’ll stay long enough and lower a tapper into that space and start absorbing’. Can I put words to it? No. I can put sensuality to it, the sense of being lovingly activated at that moment, therefore I don’t feel the labour. When you’re in an act of love, you no longer clock labour. Everyone sees labour but I don’t know about it. You’re not going to count the hours you spent making a beautiful dinner for someone you love, because it is love.

Endurance is nature and the boundary of nature is porous. For me, nature teaches us to go to the boundary of our potential, to go one step further and fall into porosity, because in that porous space we activate all our senses and we turn on, we really turn on.

Barnaby: What is the day-to-day routine of a residency like this? It sounds like you were out and about a lot.

Joshua: It was totally unpredictable. I didn’t have regular hours painting, I was like a bird, I was hopping. Hop hop hop. Look around. Hop hop.

A unique element came when I went to Killen Falls, and straight away felt the story of the drowning experience I’d had. I knew I needed to go underneath the waterfall, submerge my head and put my hands up, and have my wife photograph me.

I didn’t have any pressure or restrictions, I just let charm create the chapters. I’ve been painting for twenty-one years so I know I’m going to deliver something. The question is, was I sensual through the process; was I at the boundary where it’s humming?

Barnaby: Your first book, Surrender, is not a book to read from cover to cover, more one to drop open and read in a non-linear way. You also include a lot of detail about your personal life — the fertility issues with your wife, bullying at school ... What was the motivation behind the book’s candidness?

Joshua: I made this book for my daughter, and when I had written it I put it in away in a drawer because I didn’t have an outlet to release it. Then I was given an opportunity to have a show at Manly Regional Gallery, and the curator wanted to make a catalogue. I could visualise a traditional catalogue, but I felt like the manuscript was vibrating in my drawer, and I showed her. She said, ‘Wow that’s really heavy’. It inspired me enough to do another edit while we were deciding what catalogue to make. Then I showed [actor and friend] Richard Roxburgh and I asked him to be honest about it. He said that I had to do this and that he’d help edit it with my wife and another friend. The idea was I’d make it for that show as a unique kind of catalogue. I never thought it would have the sell-out success it had. I printed it in China and funded it all myself. It sold out and then Picador asked to see me and they’ve taken it on. So it was very organic, and I’m very wary of the fact it wasn’t written with the intention of being published.

The reason I didn’t delete the fertility and IVF part when I knew it was going public was that, in the years following my children coming into this world through love and science, I kept talking about it at shows and in workshops and stuff, and that finally led me to print. I had an awareness that somewhere I’d be going to release these thoughts.

Barnaby: The book is also an exercise in memory. How did you approach the act of remembering? Is it an act of creativity? Is it something to trust?

Joshua: Memory is creative, and it’s important that any picture or text or dance is in part inspired by, I think, connectedness to nature. When I’m in nature I’m a loving person. Sometimes when I’m cornered, I can bite — cornered by my own vulnerability and anxiety. So I place myself where I’m in abundant nature and connected to a much larger story than my own. It is then humbling when I write.

But at the same time, Richard and Jo’s edit deleted vast amounts of me verbally spewing out the pain of family and drama. Because I trusted that no matter what they did my essence was contained deep enough in the product, I let them take out about 1,000 pages, especially parts about spirituality, because they didn’t feel this was the right mechanism to release that.

Barnaby: I have a five-month old son, five months in which I’ve had a lot of exposure to your work as well. When I interact with him I have a feeling of him possessing an unreachable kind of pre-language wisdom that I sense may be quelled when he learns language and words. And when I look at your work I wonder if I’m recognising that same connection with something unconscious, expression that is not limited by the way we frame things with language. Does that resonate with you?

Joshua: I think we really have an opportunity to take the way our fathers were with us, and download new sensitivities on that platform, so we can relive our childhoods through our sons, fixing certain parts, rearranging the software. And our little ones are magnificent in their stumbling: we love their stumbling language, we love their stumbling walk; when they fall over and hit themselves it’s charming. And I think what’s really important is to keep that in our practice. We are creative in stumbling.

The other part is that my children are agents — and this is very important — for my change. They bring me at times annoyance, frustration, challenges, but they also bring me knowledge. Their clarity has infiltrated me and I’m grateful, and that will be my gift from them as they become adults and have children, my ability to see when they’re agents for my change; that’s what love is. You allow someone to assist you in upgrading your capability. The minute a kid knows that they’ve affected you in your growth, then they gain currency, they gain self-worth, because they know they’re an active member of the family, and that their knowledge is assisting the evolution of the family.

Barnaby: And how does all this translate itself into art, for you?

Joshua: I think one of the biggest things for a father to accept is that your wife has gone on to a different level since the birth of a child. From having your lover completely smitten by you, you go through the change of landscape when a mother is reactivated as carer and nurturer of this new child. The father has to quickly reinterpret what love is, because it has shifted, and many men can’t do that. If you do reinterpret what love is, then you’re learning to be more flexible as that woman aligns more with the child. If we flow with that and see love in that, then we can only get more sensual as men, because we’re accepting of female fertility and creation.

The problem is that many men can feel redundant, in servitude to the female force, but the female force runs through all my work. There’s a strong female energy running through all this, and I see that and it activates my masculine side as well.

Barnaby: So fatherhood and family allow you to tap into femininity, which then infuses your art?

Joshua: Femininity is creation and giving life, and then there’s a shift to destroying life, with the period. So with me, I have creation, I’m painting away, painting away. There’s a moment when painting is growing, growing, and then at dawn, sunrise, I start destroying it. My intellect has a natural need to destroy something that I just heralded. I keep practicing destruction so that I am transcendental, I go beyond. In this space is the creative dimension. Allow destruction, and out of destruction I will pull beauty, out of the something that collapses. I’m tapping into nature’s language, in which new life always comes out of bushfire.

Barnaby: Can you describe how art from outside of the western tradition — Aboriginal art, Chinese art, African art and so on — has had an influence on you?

Joshua: The public sometimes say to me, ‘Are you influenced by Aboriginal art?’ or ‘Are you Indigenous?’ They would probably like me to say that I am. Or they might say I’m ripping off Indigenous culture, capitalising on it. All these responses are logical to me on one level.

In my practice, in the meditative field of mark-making, line work and dot work vibrate. My study and practice have been in learning to create things that have a language other than words. I lived quite a lot of my life in communities where mark-making was line and dot: North Africa, Japan, Indonesia, Australia. I was with the Tuaregs of Algeria where mark-making is stick and paint, which leaves you with line and dot. It’s the space between lines that vibrates, and that vibration parallels the way I see things in meditation, which is in energy fields.

The point is that I’m not always claiming the authorship of what I’m making; there’s something else guiding me, and that’s maybe what connects me with cultures that come from a more ancient, older awareness. An influence from something other than our intellect.

Barnaby: Another hugely important influence on your art is the Hawkesbury River, near where you live. Have you been inspired by other artists, in any medium, who have drawn upon the river?

Joshua: Kate Grenville is the only other artist connected to the Hawkesbury that I have written to and followed, because she became an agent of nature. What she did was beyond just writing, and she profoundly changed the river for me and many people. I’m grateful for her process and what she went through.

Am I inspired by other artists of the river? Zero. Am I inspired by Japanese calligraphy to represent an oak tree? Yes; cherry blossom knowledge in ink? yes. Then convert to eucalypt over river, convert to me. It’s like Picasso, he digested anything that interested him. African art, he ate it. Next morning, he distributed it. That’s all I’m doing and it’s all we can do. We eat what charms us, then we re-interpret.

Barnaby: You don’t seem quick to acknowledge the individual visual artists who have influenced you, preferring to describe inspiration as coming from things like nature and sensuality. Are there any western artists who have stopped you in your tracks?

Joshua: I missed out on formal training as a painter, which emphasises that you align yourself with certain movements. But it really interests me when we come across an artist’s work that we are willing to go that extra yard for, and reinterpret through our own fingerprints. For me, Kate had that effect on my work. We’re unified even though I don’t know her well, I’ve never walked with her, but I feel connected to her. I feel connected to the fig tree because I sat and worked it. I feel connected to Picasso because I have eaten him and his literature and his world. I feel love, even though he was a Minotaur who ate things and ate people. I’m connected to Paul Klee. Van Gogh — recently, I keep getting startled by his magnetism and energy, and by the fact that Van Gogh’s theatre was for himself, and not performing for others; I love that intimate space that he was rolling in and anguishing in.

Barnaby: I wanted to ask you about Klee; there seem to be certain parallels between you and him in how you see art as coming from beyond. Here’s a quote about Klee from EH Gombrich: ‘nature herself, [Klee] argued, creates through the artist; it is the same mysterious power that formed the weird shapes of prehistoric animals, and the fantastic fairyland of the deep sea fauna, which is still active in the artist’s mind and makes his creatures grow’.

Joshua: What a weight off our shoulders that we’re not in complete control of our authorship. How beautiful to know that there are levels of guidance that are being handled for us. I think people who are clinically harnessed, in institutions for instability of mind — a lot of them are porous on the boundary, and our culture doesn’t know how to speak their language; but some of them are agents for change in the community, and they’re not being acknowledged as agents.

Barnaby: The Herald’s art critic John McDonald said in relation to your work, ‘I’m not convinced an artist should rid himself of negative thoughts, because this seems to remove an important element of self-criticism’, which is interesting because I would say you certainly don’t shy away from negativity, in that many of your works have fear at their centre.

Joshua: I think he was commenting on when I wrote about being fearless; I do believe that the goal of consciousness is to train itself to become fearless, which means to go to the boundary and take on what is new territory.

There are times when I have fear, but overall I align myself to being fearless. Like now: you are taking me into a garden I’ve not been in and I’m playing in it. To me, that makes my life interesting. I’ll take on these questions and I’ll play in this space with you, and I might expand your questioning, and then you’ll expand me, and before you know it the audience is clapping, the actors feel it, the producer’s stoked, money’s coming in. That’s what we want, a life that is full of water thrown in your face, and then an embrace. John shot across a message like that, which is fine, he’s saying you need those mechanisms to make great paintings because it makes them edgy and the public get to see the mechanisms that this artist has gone through.

Barnaby: Finally, we’re currently sitting among the works that arose from the residency you undertook six months ago. How are you feeling about that time, and how has your relationship changed to the artworks since then?

Joshua: You’re seeing the product of an intense period of six months while I’m also painting another show for Sydney. You’re seeing a man who is in full swing of manifesting power. So right now I’m not in post-show destruction mode where I’m dealing with not making anything anymore, and I don’t quite know where to go – that interview would happen in a few months, when I’m trying to find an algorithm that would get me back into finding charm, and then off I go again.

The bushfire analogy is primal to me. At some point I’m going to just burn off, everything is going to look smashed, but I know my seed structures pop and all I have to try and do is endure the timing until the rain comes and I sprout new life. That’s the key, holding out.