Jen and Faith met during a visit to the 2014 Sydney Biennale. Faith had previously taught visual art with Jen’s sister Lorraine Webb, in Whanganui (Aotearoa New Zealand), so they knew each other slightly; and Jen had long been following Faith’s art career, and included her work in an earlier research project and exhibition on worldmaking in art.

Jen Webb: Faith, you’re a printmaker, you’re a business manager, you’re a school teacher, you’re a polytechnic tutor and lecturer. Tell me about the progression: how you went from being a cadet in business management, to saying ‘No, damn it, I’m an artist!’

Faith McManus: I’m one of those people who actually can’t make themselves do something unless they really love it. What happened with the management cadetship was that when I started actually having to do accounting in the office, I was so desperately depressed I just couldn’t function. And I had always wanted to be an artist but … you know how sometimes you want something lots and lots, but then you’re frightened to try because you might fail, and that means failing at your whole dream? But still, I ran away from the Ceramco management cadetship and went sailing, and then found my way to a beach at Ahipara, and my birth mother came and found me, and she said ‘We don’t lay around on beaches! What are you going to do?’ And I said, ‘You know, I think I’d like to be a potter.’ I had this lovely idea of working at home and making real things with my hands. There was a place in Whangarei called the Northland Craft Trust, and there was a woman named Yvonne Rust who was a pioneer potter in New Zealand — this was a long time ago. She was building up an arts place and they had PEP1 schemes running — in 1982 or something like that. So I went there and she said I had the right look in my eye.

Jen: The potter’s look?

Faith: Well, the artist’s look. I hadn’t been there very long and I was still doing things like helping to build the kiln, helping to make clay, and hoping that I would learn to make pots at some stage. After a while she said to me, ‘Dear, you are not a mud person.’ She said, ‘You’re a colour person.’ And she was so right, but I was a bit stubborn so I just stayed on down in the dark clay pit, pottering around, til eventually I realised that she was right and I started having painting lessons.

Jen: Was that also at the Northland Trust?

Faith: Yes. I was with Yvonne one day a week, and then on the other days I helped build the kiln. And then I started making work, and had that idyllic idea about living in the country and making paintings. Very naïve, but … I didn’t go to art school until I was 27. I had gone to university and did part of a literature degree. Really, that was because I just wanted to have a year reading novels. I’d been married, and I just needed a year to sort myself out. And then I went to art school and it was there I found the right place. My nan, who brought me up, she expected me to go to university and get a degree and so I was kind of programmed to do it, and I needed to do it.

Jen: You were sixteen-ish, and you knew you wanted to be an artist: so even as a little girl, was there a drive …?

Faith: We had this great veranda at the farm, which was closed in, and I had my studio on the veranda, when I was a child. I painted. See, my actual mum, who used to come to visit, she wanted to go to art school but didn’t really know about it and wasn’t very confident. You know in New Zealand there’s that generation of contemporary Maori artists who trained as art advisors with Gordon Tovey?2 Well, my mum was supposed to train as one of those, but she got pregnant with me instead, and that threw her off the rails. So there was always that thing about art: that it was her thing. But I loved painting, and I had my paints out and I had a table on the veranda, and it was my spot.

Jen: Did you get art at school too? And was there a good art teacher?

Faith: No. The teacher at high school used to just write work on the board and then go away and lock himself in the office. So I didn’t actually have any tuition.

Jen: But clearly you did have that look in your eye.

Faith: (Laughs) Yvonne was wonderfully psychic like that. And I loved art school.

Jen: Which art school did you go to?

Faith: I went to Otago. Because I’m from the far north I wanted to go as far away from there as possible, not realising the extreme culture shock and the ‘everything’ shock. I went there thinking I was a painter, but Marilynn Webb3 was the printmaking lecturer and she was so fabulous: I fell in love with her.

So my whole art education is Eurocentric, and I didn’t actually think of myself as Maori until I got to art school and I found myself … well, I suppose because I don’t look particularly Maori, I’d find myself in a room and people would be talking about Maori as though no one in the room was Maori and not necessarily saying things that were very comfortable for me to hear, so I’d have to start piping up and say Excuse me, I’m Maori, I’m not really very happy with that …

Jen: So you actually got politicised in terms of your culture because of that experience in the classroom. Not Maori art, but Maori culture.

Faith: I suppose the thing with where I came from is that there are a lot of people like me, who are a mixture of English, Maori, Dalmatian; whereas when I went to Dunedin whenever I saw someone who was brown I’d just smile maniacally at them. Really, I went to te reo classes4 in Dunedin cos I was desperate for hugs (laughs).

Jen: Cos nobody hugs in the Scottish community down there. (laughs) That’s so funny, and sad. So why printmaking? What triggered you to your genuine creative future?

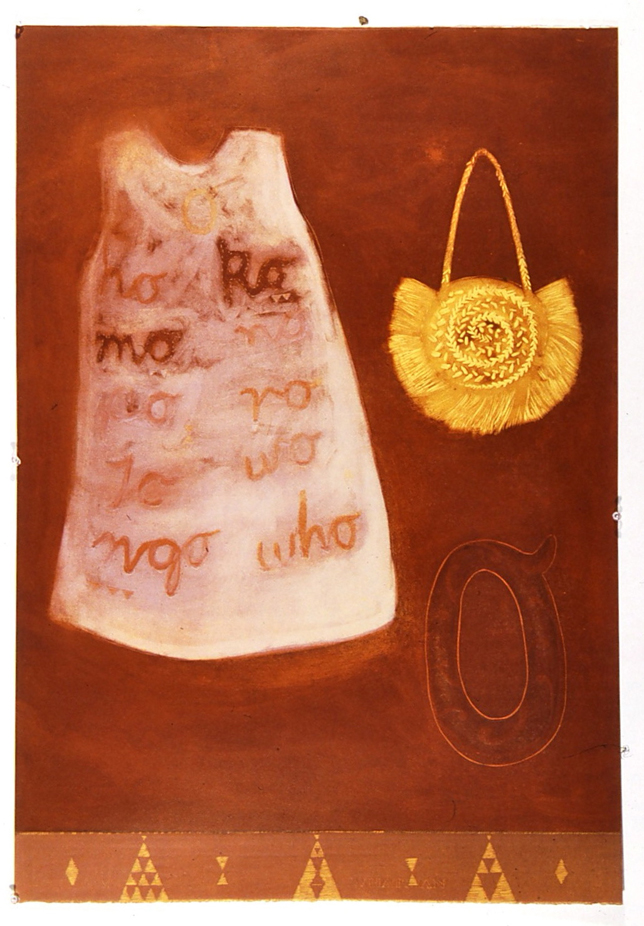

Faith: I really liked woodcut. And it was interesting because there’s the whole Maori carving thing; I liked cutting into wood and I love colour, so I loved inking up colour and printing it. And Marilyn was a really fabulous teacher. She really didn’t impose anything onto you. She genuinely believed that you bring out the person themselves, and so my work slowly evolved and became genuinely my work. And in my Honours year I set off to make work that was about the stories of my female tūpuna, or ancestors: my Nan and her mum and my grandad’s mum as well, cos you know there’s lots of strong women in the family, strong role models, so I’ve always thought of women as strong people. And I started making work about those stories. I was using the dress as a metaphor so I made giant, two metre prints. It started off with the ubiquitous black dress worn by the kuia;5 Nanny Mac, or Kararaina, she was supposed to be as wide as she was high, so I was drawing on stories that I had been told in making these prints. And I also combined that with weaving. My nan had taught me raranga, or to weave, when I was little, so it was one of those things that was Maori that I felt I could genuinely draw on, because it was in my experience. Because I wasn’t brought up going to the marae6 and my nan, who was Maori and English, wasn’t into Maori stuff at all. You know that generation … I didn’t even know she could speak Maori. I never heard it.

Jen: I guess she grew up when Maori language wasn’t allowed to be spoken in schools?

Faith: And her dad was English and he’d been to Oxford, so you know; on one side of the ledger: she loved her dad, and she didn’t want to go to the marae and, you know, it was just her choice.

Jen: But she still did weaving …

Faith: And she made sure that her daughters got sent off to boarding school because she didn’t want them to be servants. I suppose she was a very early feminist, in a kind way. So the printmaking … it was a vehicle for me, and it seemed like a really natural vehicle. I liked the feeling of making marks in wood. I liked the fact that you couldn’t always get it right. I was talking to Lorraine7 last night about how much I like teaching second-year painting, because my work has a lot of the same concerns as painting.

Jen: In terms of?

Faith: Colour and space and size, usually. But I do like the feeling of carving into wood. I like making marks that are very definite.

Jen: Is it sensual, or is the quality of drawing that right line, drawing with your blade?

Faith: It’s both of those things.

Jen: So you’re literally carving out a world, a space.

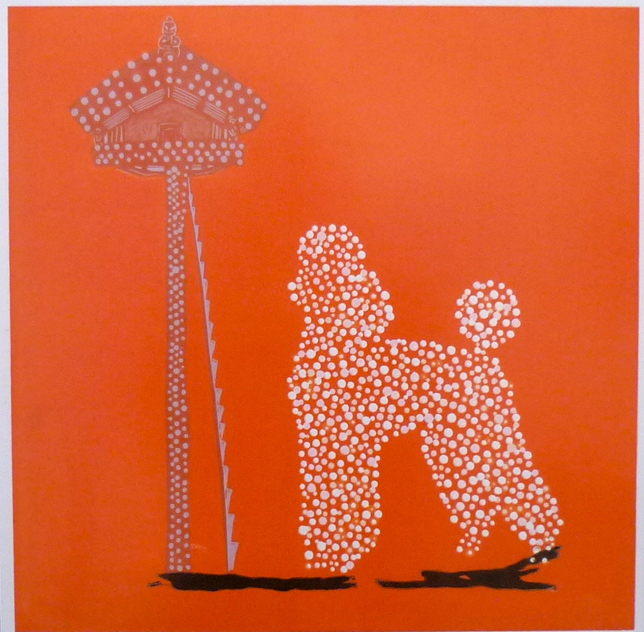

Faith: Yes, it’s just something extremely satisfying. Although, I don’t make such big work now because my hands hurt. I carved like a nutter for years and now my hands get sore, so my last series of work I made with the drill, with dots,8 that was really done like that cos I’d hurt my body and I couldn’t actually use my tools. I’m recovering now.

So I didn’t sort of consciously set out to do Maori work; what I was interested in was my family history. I draw on things that are from my family history, and sometimes those things, like the raranga patterns, are a link to Maori things. But I also draw on feminist things, and craft traditions.

Jen: And on non-feminist stories? I’m thinking of your Riders of the Red Manuka works.9

Faith: Oh, I have lots of different ways of starting work, and because I also work as a lecturer and a tutor, sometimes things stack up because you can only get to them so quickly. My mum, Anna Karena, said to me, ‘Papa was one of the cowboys of the Red Manuka.’ And I just loved that phrase. She said that to me when I was working in Whanganui and I was visiting up north, and I tucked it away and said one day I’ll make work about that. And when I got sick and we went back home to the far north I sort of thought, oh, now I can find out about that.

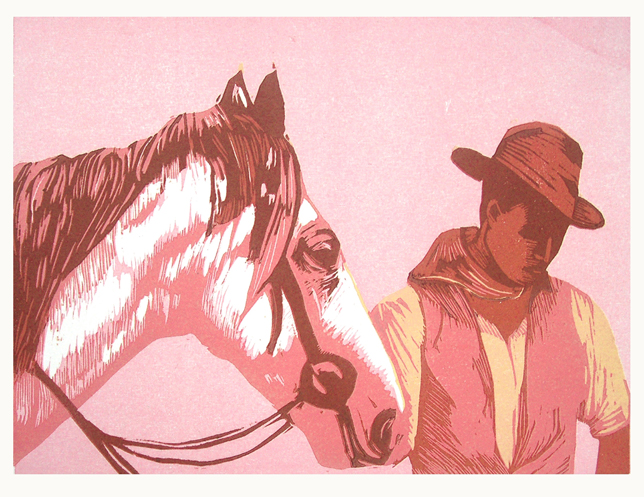

The story was that there had been a cowboy movie made in the far north, based on Zane Grey’s novel Riders of the Purple Sage,10 and it was made in 1926. There were film stills from Riders of the Red Manuka, and there were just gorgeous photos of Maori guys in cowboy gear, which did look like they could be filming.

Jen: On their stocky little horses?

Faith: Well that was actually just the guys from Te Hapua, which was very hilly. The other guys, like my papa, were actually from not hilly country so they had decent sized horses.

So yes, I like hybrid stuff, because that’s my kind of background. I’m drawn to stories that have that mix: you know, where cultures meet. So I like the idea of the Hollywood movie, cowboy, Maori, and Northland. It’s just bizarre. I found out that it was really the National Publicity Office doing filming and actually that was just how they dressed.

Jen: So they weren’t in costume. They were just ‘those guys’ from the twenties?

Faith: That’s how they dressed! They loved cowboy movies. And there’s lots of research about how much Maori loved cowboy movies and people getting up and firing guns excitedly in outdoor movie theatres (laughs).

That’s the only work that I’ve made that’s been about cowboys. Most of the work has been more, I suppose, woman-based, but I really enjoyed doing it, because of the quirkiness of that mix. And it was interesting for me because it was the first time I had made little work and editions since art school. I’d just been making big mural prints and installation-based work, and then because I was making that work at home in the far north and I knew that people who were related to those people would see it, it was the first time I really cared about people looking like who they were. Also, I actually wanted to make work that I could give away, and also that I could sell. I’d never really thought about an audience in that way before but it was really important to me that because I had made editions I could feel that I could say, ‘Here, have this’, and that was a nice feeling.

Jen: So all that time before, all the years you were making work, you weren’t thinking about the audience, but you were thinking about the work itself; is that right?

Faith: Yes, I was just driven by my need to make the work. I think I thought of myself as a storyteller.

Jen: But in colour, and line, rather than in word.

Faith: And in shape. And all sorts of different things stimulated the making. I was invited to be part of a Maori women’s group called Kauae … kauae is the woman’s facial moko,11 and other members were Kura Te Waru Rewiri and Colleen Waata-Urlich,12 and people who were older than myself, and I think we had our first group show at the public gallery in Gisborne. I don’t speak Maori, but my mum does, so if I want to have discussion around a particular thing I’ll ring her up and we’ll talk about concept, and we’ll title my work. I was making this work about my nan, the person who was ‘mum’ when I was growing up, and one was a great big gardening dress — and it was Mum — and a little ‘me’ dress, and a kumara bed because my grandparents used to grow kumara;13 and also the seed bed. It was a really beautiful print; and the title was to do with the passing down of knowledge through the generations. I sent it over and the curator rang me up and said, ‘You know, the spelling isn’t right on your title’, and I wasn’t feeling very confident and I just said ‘Oh, ok. Well we’ll just put it there in English.’ But in actual fact, what I should have said was, ‘Oh it’s just a dialectical difference.’ I should have said, ‘My mum gave me the title; just put it on as it is.’ But I felt insecure. And that’s that insecurity in Maori context, because you don’t have the language.

Jen: So as a hybrid you’re not quite right in either space?

Faith: Yes, but in actual fact I’ve got to a really nice place where I just feel like I’m me and I’m right whichever space it is. But that’s because of exposure, and going back home and being part of the Tai Tokerau Maori artists group,14 and being just part of doing things, you know part of workshops and hui15 and travelling over to work with Aboriginal artists and then organising for them to travel. So the confidence has grown that I’m just who I am, and there are a lot of people who are a mix. Some people have really deep knowledge and training in traditional ways, and other people don’t and it’s fine. We can all just fit in.

Jen: I was interested, when we did those interviews for the Making Worlds exhibition,16 that you and Kura and Lily17 had quite different views on the making of worlds in a cultural sense. Obviously all of you were more connected to the land and culture than, say, the pakeha artists,18 but it still wasn’t a uniform voice.

Faith: Oh no, and it wouldn’t ever be. That’s like when people talk about ‘Maori think this’ or ‘Maori do this’; well what rubbish! (laughs) I was thinking about that story, and I remembered feeling insecure, and that was what made me do my next series of work which was based on singing Maori vowel sounds. When you start te reo classes, you sing the vowels to the tune of ‘Stupid Cupid’:19 you know, ‘A h aka ma na pa ra ta wa nga wha …, and so I made clothing shaped with the idea that the language that you have is like the garment you wear and it alters the way, shapes the way, people perceive you; and also the way you perceive the world. It kind of connects to a great Virginia Woolf quote that she had about that. To paraphrase Virginia Woolf — Clothes are not just frivolous things. They affect the way the world sees us and also the way in which we view the world.20 Because, you know, different concepts belong in different languages, and so they are all just ways of dealing with, of perceiving, the world.

Jen: Did you notice a change in yourself as you started learning te reo?

Faith: No, because I sort of stopped (laughs). And actually, to be quite honest, I think I’m one of those people who doesn’t have an ear for languages. Although when we’re in Europe I’m very good at gesturing and smiling and making myself understood … I don’t actually have an excuse for it. I just stopped classes. And part of it is that I’ve always been more interested in making my work; and I know quite a lot of words so I can understand certain sets of things.

Jen: You talked about finding ways to get started, and stacking up those ways. Can you talk a little bit about that process?

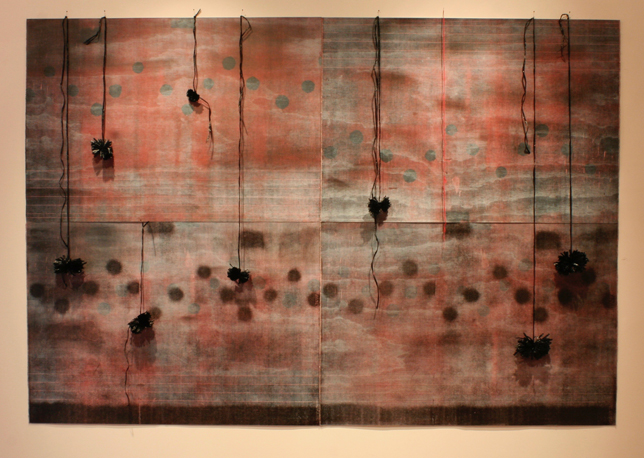

Faith: It’s always different. And that’s one of the things that I enjoy being able to share when I’m teaching because starting points are always different for me. I never ever start in the same way. So with the ‘h aka ma na’ show, the vowel suite — that was an emotional response. An earlier one was stories: I wanted to tell stories and make prints about these wonderful powerful women. But there have been other series of prints that have responded to the environment. When I first went home up north and I was sick, I went to where I was brought up, and where we have a house; but I was teaching part-time in Whangarei, and driving two and a half hours down there to go to work. So I would leave very early in the morning and sometimes it would be really misty. There’s a town partway down named Moerewa, which is a freezing works town, and which is not a very attractive place during the daytime, but when you drive down the hill in the mist, it’s like a beautiful ancient Chinese painting, all greys and blacks and moisture and layers. And responding to that mistiness and grey and black and silver was the starting point for a really dreamy series of prints based on shadows of little flax horses. I actually made those little horses and took photographs way back in Whanganui, but I didn’t know what to do with them. I had woven these little flax horses and then I had put a white sheet in front of them, hung them on the clothesline, and then taken photographs of these strange abstracted shadows moving around in the wind. And then, six years later, I worked out a technique of printing fuzziness that allowed me to layer up and make these little photographs into big works. I stick things in file boxes; little photographs, or a little clipping of a poodle skirt or … little seeds, I suppose. And then sometimes it’s knowing — suddenly working out — how to do something technically, as well.

Jen: Like being able to print with a fuzzy edge.

Faith: Yes, when I realised that you could cut the front of the block and then cut the back of the block and print that, you’d get a big soft fuzzy thing instead of a sharp, crisp print.

Jen: That’s interesting. I’ve been interviewing senior poets I told you about and a lot of them are very old and very, very distinguished, and they’re nearly all saying that they are always working beyond their technical ability. That’s why they’re still making work; they can’t get it right because every time they learn something they need to learn something more and so they’re always stretching themselves. Is that true for you too, in printmaking?

Faith: Yes, yes. Working out the how to and the why as well.

Jen: Not just responding to the emotional, the visual, the imagistic stimuli, but actually the technical aspects as well. How do you do that? How do you deal with the techniques?

Faith: Well, the last decade for me has really been a kind of strange period, because I got so sick in Whanganui that I couldn’t work with oil-based inks and I couldn’t go into a normal print studio, so everything has had to become non-toxic and stuff like that, which did cramp my style somewhat. Fortunately in January I found the Akua inks; and the woman who invented those inks thought Akua was a Hawaiian word for water. Actually it’s akua, so it’s the ink of the gods. You know like in Hawaii: akua; in Maori: atua. So I am using ink of the gods!

My husband David is an artist as well, and he inspires me because he makes beautiful work and he’s very good at working out how to do everything. He showed me how to lay gold and silver leaf, so I’ve been using those as well for the bling factor. Seeing my colour couldn’t be so bright, I’ve been blinging my prints.

I suppose one of the things, too, is that I don’t think I self-censor any more. I think I just make whatever I want. I don’t think ‘oh, I shouldn’t make this’ or ‘I shouldn’t do this’, and that’s a really good feeling. I don’t know that I was conscious about it when I was doing it; and actually I’ve always been a little bit contrary because I can remember fighting at art school against the idea that certain work, men’s work, was described as powerful or strong, and other work that was pale was described in other ways that were less complimentary. I deliberately chose to work with pink, as a power statement.

Jen: Yes! But how do you know when you’ve actually finished with a theme, a project, a set of images?

Faith: I’m just quite simply no longer interested in it. And another one’s moving forward. I’m in a really strange space in my work at the moment because I’ve been finishing off things and I’ve actually reprinted something for a very dear friend who’s eighty who wanted me to go back and reprint her something that I’d made and she had never ever got to purchase, and she’s been buying one of my works from every series since she met me. She’s the one who has the lovely collection of Ralph Hotere.21 So I’ve been finishing off things and I’m making, not working, on big body of work, but I’m making things targeted for a print exchange. Having the international Indigenous gathering in January, I met some people I really connected with in who are in America and Hawaii, so I’ve kind of been organising little projects for both myself and my students, so I said yes to a print exchange with Melanie Yazzie,22 I work with a group of Maori printmakers. We do a show together every couple of years so I’m working towards that.

Jen: So you go from the individualistic and the very private studio space to the broader community of artists?

Faith: This is just different … It’s a different year for me. I do have some work sitting here that I haven’t started yet. It’s orange and white. I can see it, but I just haven’t … I’ve got these little things that I’ve said yes to do, and I’ve got to actually do this year because I’m feeling quite tired; and not having a huge studio I just have to do that little kind of step-by-step thing to keep my momentum through the year. Because unlike universities, poly-techs do not give you sabbaticals and this is my seventeenth year of teaching.

Jen: Yeah that’s a hell of a commitment. A lot of creative people are teachers, that’s how most of us make our living, and you’ve been doing it for seventeen years … do you find that it energises you?

Faith: I do. I love teaching … My nan who brought me up was very kind and she was a fantastic teacher. And then I had Yvonne Rust who was the different sort of big, expansive, over the top kind of teacher, and then I had Marilyn Webb who was kind of quiet and refined with a very wicked sense of humour, and very down to earth. So I’m very inspired by those people, and I really do believe in passing on knowledge. One of the things about being at home is I get to work with more Maori students, because we have more Maori students enrolled at Northland Polytech than I ever encountered at Whanganui Polytech. I was given a paper to teach called Pacific Studies, a first-year paper, which is supposed to provide a context for thinking about ourselves as being a part of the Pacific. And it’s supposed to cover pre-history and settlement, settlement of the Pacific and navigation, and then I do the artists of Captain Cook’s voyages and then I link this all in to contemporary Maori and Pacific art.

I’ve enjoyed the creativity of working out how to teach that, because I came in the first year and half the students failed, and I thought, ‘I can’t just come in and do a lecture and go away again. It just doesn’t work.’ Not all of the students have been very successful at school and so the academic approach didn’t work. So I constructed a paper based on all of the things I would have liked to have learned. The students study taonga.23 What I do to start off with is I have a wonderful slide show of contemporary Maori and Pacific art and I get people to choose someone that they respond to and then that links to a topic from prehistory. So if you had Filipe Tohi and there’s lalava sculptures, then that will link to sennit lashing.23 And then they have to study that first, and then when they get to write their essay about the contemporary artist in the second semester they understand all this kind of background knowledge, and it’s really successful.

Jen: And are they passing? And enjoying it?

Faith: Oh yes. Doing really well. And the first project is an oral presentation: that’s a preferred Maori way of presenting, so it takes that into account. And people really love the research. We don’t just look at books, we go to the museum as well and we respond to objects. That’s really successful. It’s quite interesting too because I encounter a lot of students who look very Maori but don’t necessarily know anything about Maori culture, or may have had an unpleasant experience in their upbringing, or have married someone who is European, and don’t have anything to do with it. So it’s sometimes quite a life-changing course. There’s this lovely woman who was doing her seminar and described herself as a ‘plastic Samoan’ and I thought, oh, we’ll have to talk about that one.

Jen: Synthetic, in other words? Because she might look Samoan, have Samoan cultural background but no knowledge?

Faith: That’s a bit sad. Anita Heiss, who is an Aboriginal author, may have invented the term, but she certainly uses it; it’s ‘concrete Koori’:25 Koori refers to Indigenous people from New South Wales especially; and concrete is because they’re brought up in cities. And in a way you can feel that you’re being deracinated, immersed in European culture, but actually you’re not, you really are Aboriginal, it’s just a different way of being Aboriginal. That’s concrete Koori, and I like that. And I think it’s probably more powerful than saying ‘I’m plastic’. Concrete is tough, it’s heavy and in place. It knows what it is and it doesn’t get melted.

Jen: So, still on this idea of collaborations; can you tell me about the International Indigenous Artists Week you had in January this year?

Faith: Yeah. I think it’s the seventh gathering, funded by Te Atinga.26 But that was really fun because we hosted that in Tai Tokerau and so I was one of the co-organisers of the printmaking workshop. I provided the presses and racks and all that kind of stuff. I met great people, had a great time. Commonalities, making connections really: I think that’s one of the things I love about those indigenous hui – it’s the commonalities and the making connections.

Jen: And by Indigenous you mean pan-Indigenous: North America, Australia?

Faith: Yes. We had people we had worked with previously in Australia, people from Hawaii, from American Samoa, from North America; where else? A Celtic potter from Somerset. He was seven foot and he looked like Gandalf. So it was really an interesting group of people. There would be a carving area and a painting area and a printmaking area and weaving area and a tā moko27 area, et cetera. But people crossed over and moved around, and there were lots of cool collaborations.

Jen: So not just a cultural interchange but also an art making interchange?

Faith: People were signed up for a particular area but then they’d go off and do something else. It was quite funny because Bob Jahnke, who’s the professor at Massey, he came in and sat at the printmaking table and Bob had been doing a linocut and one of my students who had graduated sat down — he didn’t know who he was — and said, ‘Oh, who’s doing that terrible linocut, that really doesn’t look good’. So Bob said, ‘What would you do if you were …?’ The student says, ‘I’d get out the knife and crisp up those edges and make them nice and smooth.’ He didn’t actually realise that it was the person whose Masters program he was going to be applying for (laughs), he was just teaching him how to make a print.

Yes, so there’s a nice movement around it and a real mixture of ages, you know. Lillian Pitt who is a Native American artist who’s a famous ceramicist but also does silver jewellery: she was in our printmaking group because she’s kind of allergic to glazey things now, so she was in our printmaking group and she was just delightful. I made friends with a lovely professor from Hawaii, Maire Andrade. She was the one who told me about Akua being the ink of the gods. And there was Marwin Begaye who teaches in Oklahoma; one night I said ‘Hey Marwin, do you wanna do a student print exchange?’ and he said ‘Yeah, Faith. Fantastic!’ And that was it. That was the organising of the print exchange for our students.

Jen: What happens in your head after this sort of experience? Such a lot of stuff all coming together, looking at different kinds of practices. Do you find yourself thinking and feeling differently about your work, or are you just really happy that you experienced it? Does it do something to you creatively?

Faith: Well, one of the things was that, because I was one of the organisers, I probably didn’t focus and make serious work; I was looking after people, and I was printing tee shirts for people, I was taking someone off for a little drive. But in terms of creativity it sparked some interesting ideas. I was telling you about talking with Vanessa who used to be my student about this idea of this character that we would create a show around, called Pare Bunting, so that’s something for the future, so that was nice to just think about doing more work collaboratively.

In terms of going back to teaching, that was quite hard because there’s been a lot of changes in education, and the Polytech had actually closed the Maori art programs down at the end of the year. It was a very strange feeling; I felt kind of sad and angry. We only had certificate level programs, but they are the programs that get Maori students moving into the degree, and we get lots of older students as well, so the certificate program is the entry point. But the Maori certificate programs in contemporary Maori art and in weaving and whakairo have all been closed down.

Jen: Whakairo is?

Faith: Wood carving.

Jen: I should know that, sorry.

Faith: It’s okay. Well whakairo is really ‘pattern’; whakairo rākau is wood carving, but people will just say whakairo when they mean carving. Those had been closed down. I felt quite sad about that and I think I felt a bit angry as well. So I went back to Polytech. There were about seven of the Maori students from Northland Polytech who had worked at the huis, volunteers in the kitchen and in the exhibition, and probably twelve-hour days. They were magnificent. And they were all buzzing and they’d made all these connections and stuff. Then we went back and I sort of felt like ‘Oh, well, everyone else is gone. Te Hemoata’s not here teaching weaving, Shane’s not here teaching carving, Lorraine’s not here teaching contemporary Maori art.’ And I actually felt quite isolated. So that was very unsettling. We were living in a catchment area which is a lot of Maori population, and yet there was nothing there. We get lots of students come onto the degree who are Maori and who don’t necessarily want to do a Maori degree, they want to do an art degree; but there are some who only would approach education through that door that says ‘Maori Art’.

Jen: I know we have to move on, but I have another question I want to ask you; it’s about bodies. You’ve had a bad reaction to inks, I know Lorraine had a bad reaction to turpentine; there’s your friend from North America who couldn’t handle glazing any more. We’re not just working with our heads and our eyes and thinking, we’re working with our bodies. What do we do with our creativity when our bodies won’t permit us to work in the same way anymore?

Faith: I think we just adapt. Because the desire to create is so much stronger than any kind of sickness and pain. You just find another way to work.

Jen: So for you it was going from carving to drilling?

Faith: Yes. But that was a temporary thing. It was when I thought I wouldn’t be able to make art at all because I was so sick that even somebody wearing a bit of perfume made me vomit. When I thought that I couldn’t make art any more, that turned my whole life around. That’s when a lot of my thoughts turned to wairua things, the spiritual side of things, and I realised that I had really thought that my whole everything was an artist and I couldn’t be happy unless I was an artist. I got to a peaceful spot in myself where I realised that I could just be, and that was fine. That’s better. I don’t have the feeling of desperation.

Jen: Is that a different kind of creativity? — thinking, like you said, the spiritual side of stuff. Or do you feel you’ve gotten into a more religious side of things?

Faith: Religious is probably not the right word. But I meditate, I have a spiritual practice of meditation and contemplation and thinking. Changing the ways I think. That’s important. That’s really a central thing for me now.

Jen: And the last question; a slightly sad one. When we were talking yesterday you mentioned just briefly the idea of downward spiral of energy.

Faith: I think about some of those things in the last ten years, when I got sick, and I had to deal with oh my God, I can’t make art. I’ve got to give up my job. I loved my job in Whanganui. It was like going to a sandpit and playing all day and then not being able to … Like, I couldn’t even go into the print room without projectile vomiting. That was big. So that spiralling thing I suppose is like when we get sad or upset we can move deeply towards that upsetness and it just builds momentum. A bit like that lovely coloured spiral in the exhibition. You know you can go towards it; but when it’s upsetness it’s probably a lot darker.

Jen: It’s more of Anish Kapoor’s Void and less of Jim Lambie’s spiral?28

Faith: Yes. I suppose what I’ve learned through mediation is really that you can actually just stop yourself. And you can reframe what you’re seeing and what you’re experiencing. And so that’s what I had to learn when I got sick.

Jen: A spiral is a good metaphor to use. Years ago now, I was at a conference in Christchurch, and the Maori poet and scholar Robert Sullivan was the keynote speaker. He was making the point that Maori culture and Polynesian culture are not in a box, but spiral; and a spiral can go out, or in, go up or down.29 And if you’re on the spiral, as long as you’re moving then you can get yourself to the place where you can make something that matters. I really like that, so when you said yesterday about the downward spiral of energy, there’s something terribly tragic about that – driving yourself into the ground — but because it’s a spiral it has dynamism, and you can go back up again.

Faith: I remember going to this personal growth thing when I was twenty-five and it was about success, and these people, these Americans offered this model which was the infinity symbol. And they said most people think about life as achieving step by step. Climbing the step, the ladder, you know. You’re always climbing, striving. And they just talked about it as an infinity symbol where you have time when you’re internal and you’re inside, and then time when you go outside and share in the world. And that cycle may be short or it may be longer … I love that. I have never forgotten that. That has been with me for all that time. Because it relates so much to the spiral.

Jen: I wonder if, say, you were a lawyer, you would need that linear progression. But if you’re a creative person …

Faith: You’ve got to be internal.

Jen: Otherwise how do you find the space and make the work? So maybe that infinity symbol cum spiral is worth looking for, and it’s worth giving yourself over to the darker side occasionally.

Faith: I think that’s one of the things I’ve really liked about living so far from work. Because I’m driving home for two and a half hours I can try and leave work behind, and I just have more internal time. And when I go home I don’t want to go and visit people, I just want quiet time. Cos you’ve gotta have that or you can’t make stuff. I know if I’m not making stuff, then that mental activity gets taken up with thinking about students or teaching. So, there’s got to be something going on in there. I’ve actually got to be making stuff so there’s space in my mind for me.

Notes:

1. PEP — the Project Employment Programme — was a scheme introduced by the New Zealand National Government in the early 1980, as an amendment of the Labour Government’s TEP (Temporary Employment Programme, 1977–1980). Both schemes encouraged employers, unions and community groups to offer paid work to unemployed people, but the PEP was ‘far more tightly structured than TEP jobs and much shorter term’; see Cybèle Locke, Workers in the margins (2012).

2. Gordon Tovey (1901–1974), as supervisor of the arts and crafts section of the Department of Education, was something of a catalyst for the renaissance of Maori art — or for its recognition in Pakeha (white New Zealander) culture by bringing Maori art into the primary and secondary school curriculum. See Michael Dunn’s New Zealand painting (2003).

3. Marilynn Webb ONZM (1937– ), an artist and art educator, also worked as an art adviser for the Department of Education in Auckland and Northland, and for the Northern Māori Project. See Bridie Lonie, Prints and pastels 1966–1990, (1992).

4. te reo: Maori language.

5. kuia: women elders in Maori society.

6. marae: meeting grounds: a complex of buildings that belong to a particular Maori group, used for important events.

7. Lorraine Webb, New Zealand artist, teacher of painting and drawing and a Fellow at the Quay School of Arts, Whanganui (also a former colleague of Faith, and Jen’s sister). See ‘Lorraine Webb’, in Docking, Dunn and Hanfling, 240 Years of New Zealand Painting (2012).

8. This was for a series of prints titled Not a Post-Colonial Poodle, launched at Solander Gallery, Wellington, in July 2013.

9. Riders of the Red Manuka was a series of woodcuts Faith produced and exhibited at Solander Gallery in Wellington during 2010. These works respond to the story of a 1926 cowboy movie set in the Far North of New Zealand, with Maori men as the cowboys.

10. Zane Grey, Riders of the purple sage (1921).

11. moko is the name for a traditional Maori tattoo, typically on the face.

12. Kura Te Waru Rewiri is an artist and educator of Ngāti Kahu, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kauwhata and Ngāti Rangi descent. See Camilla Highfield, Kura Te Waru Rewiri (2000); Colleen Waata-Urlich ONZM (1939–2015) was a ceramicist, artist and educator of Te Popoto o Ngāpuhi ki Kaipara and Te Rarawa descent; see Helen Schamroth, 100 New Zealand craft artists (1998).

13. kumara: New Zealand sweet potato.

14. Tai Tokerau Maori Artists Collective, based in Whangarei, Northland.

15. hui: Maori term for a gathering.

16. L Webb and J Webb, Making worlds exhibition, Whanganui New Zealand: Edith Gallery (2011).

17. Kura — see note 12; Lily Aitui Laita, artist and art educator, of Pakeha, Samoan and Ngāti Raukawa descent; see Bernida Webb-Binder, ‘Pacific identity through space and time’ (2009). Kura, Lily and Faith were all featured in the ‘World making’ study and exhibition — see note 16.

18. The ‘pakeha artists’ (or, rather, the artists who are not Maori or Samoan) in that exhibition were Chaco Kato, Kate Lepper, Helen Manning, and Lorraine Webb. See J Webb and L Webb, ‘Making worlds’ (2013) for a discussion of the project and its findings.

19. ‘Stupid Cupid’: a 1958 hit sung by Connie Francis, written by Howard Greenfield and Neil Sedaka.

20. Woolf’s essays, particularly ‘A room of one’s own’, and the section titled Women and Fiction in her Selected Essays (2008), as well as her novel Orlando (1928), consistently raise arguments against the ‘feminine’ principle, as well as objects and activities associated with women, being considered frivolous.

21. Hone Papita Raukura ‘Ralph’ Hotere ONZ (1931–2013) was a major New Zealand artist of Te Aupōuri and Te Rarawa descent, who also worked closely with celebrated New Zealand poets Hone Tuwhare and Bill Manhire. See Kriselle Baker and Dunedin Public Art Gallery, The Desire of the Line (2005).

22. Melanie Yazzie is a Navajo artist; see Lisa Tamaris Becker and Lucy L Lippard, Melanie Yazzie (2014).

23. taonga: Maori word for a treasure, something highly valued.

24. Lalava sculpture is a Tongan art form, where sculptures are made by lashing coconut straw; binding, or lashing with sennit, is widely used also in Maori art.

25. See Anita Heiss, Am I black enough for you? (2012).

26. Te Atinga is the Contemporary Māori Visual Arts committee of Toi Maori Aotearoa, Maori Arts New Zealand. See https://www.teatinga.com/.

27. Ta moko: Maori tattoo art.

28. British sculptor Anish Kapoor has, since 1985, produced a range of works titled, or on the theme of, the void. Scottish artist Jim Lambie presented a large floor-based work, Zobop (2014), in the 19th Biennale of Contemporary Art in Sydney, 2014. While not a conventional spiral, it had a similar impact; he has since produced another large floor-based work and installation titled Spiral Scratch, exhibited at Pacific Place in Hong Kong (2018).

29. See Robert Sullivan ‘The English moko’ (2005).

Baker, K and Dunedin Public Art Gallery 2005 The desire of the line: Ralph Hotere figurative works, Auckland: Auckland University Press

Becker, LT and LL Lippard 2014 Melanie Yazzie: Geographies of memory, Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Art Museum

Docking, G, M Dunn and E Hanfling 2012 240 years of New Zealand painting, Auckland: David Bateman

Dunn, M 2003 New Zealand painting: A concise history, Auckland: Auckland University Press

Grey, Z 1921 Riders of the purple sage, New York, NY: Harper and Brothers

Heiss, A 2012 Am I black enough for you? Sydney: Random House

Highfield, C 2000 Kura Te Waru Rewiri – a Maori woman artist, Lower Hutt: Gilt Edge Publishing

Locke, C 2012 Workers in the margins: Union radicals in post-war New Zealand, Wellington: Bridget Williams Books

Lonie, B 1992 Prints and pastels 1966–1990: Heartland, Dunedin: Dunedin Public Art Gallery [catalogue]

Schamroth, H 1998 100 New Zealand craft artists, Auckland: Godwit

Sullivan, R 2005 ‘The English moko: Exploring a spiral’, in H McNaughton and A Lam (eds), Figuring the Pacific: Aotearoa and Pacific cultural studies, Christchurch: University of Canterbury Press, pp. 12–28

Webb-Binder, B 2009 ‘Pacific identity through space and time in Lily Laita’s Va i ta taeao lalata e aunoa ma gagana’, in A Marata Tamaira (ed), The space between: Negotiating culture, place, and identity in the Pacific, Honolulu: Center for Pacific Islands Studies, pp. 25–34

Webb, J and L Webb 2013 ‘Making worlds: Art, words and worlds’, Journal of humanities research XIX.2: 61–80

Woolf, V 1928 Orlando, London: Penguin

Woolf, V 1929 A room of one’s own, London: Penguin

Woolf, V 2008 Selected essays, Oxford: Oxford University Press