Australia and many other countries around the world face a significant population shift. With a fast-growing ageing population, increasingly new issues of varied complexities arise that will require new perspectives to solve them. In this paper, art and design approaches have been presented into aged care to address issues of elderly people’s social isolation in the long-term residential care facilities. A design solution — ‘Wearable Memory’ — has been developed to raise awareness of the value of reminiscence, and to provide intervention to reduce traumatic memory. The co-design process allowed key stakeholders to be involved from the beginning of the project. Wearable Memory can play a vital role in digital storytelling and social bonding within the senior citizens’ culture and community, while providing integrated support and intervention towards their reminiscence.

Keywords: Co-design — healthy ageing — multidisciplinary stakeholders — autobiographical memory — reminiscence — Wearable Memory

Introduction

The world is ageing; this has been tagged ‘the ageing tsunami’ and even branded an impending catastrophe (Peng & Scharoun 2016; Scharoun & Montana-Hoyos 2017; Victorino, Chong & Pal 2003). In Australia alone, the older population is estimated to rise to 8.7 million by the year 2064, with almost one in five being over 85 at that time (Australian Institute 2018). We are facing both the challenges and the opportunities associated with this ageing population, in Australia and beyond. Rapid advances in science, technology, medicine and health care more broadly, along with increases in government regulation and patient expectations of health care and service delivery, are prompting the search for design solutions to support high quality, effective health care (Britton 2017; Australian Commission 2009; DiGioia & Shapiro 2017; Peng & Scharoun 2017; Picard 2017).

This paper explores the role of reminiscence in ageing, and how older adults can use autobiographical memory and life narratives to encourage healthy reminiscence, enhance their social connections, and reduce the harm of traumatic memories associated with loneliness and depression. Social isolation and loneliness in the ageing population are precipitated by a number of factors, including living alone, health problems, disability, and sensory impairment (Bailey 2017). Major life traumas, including the loss of a spouse or friends, significantly increase older people’s vulnerability to emotional and social isolation (Fiske, Wetherell & Gatz 2009; White & Wild 2016). Besides the feelings of sadness and loneliness, the reduction of social networks and increased isolation can trigger a variety of detrimental physical and emotional effects in the elderly, leading to instability and insecurity, and even increasing the risk of mortality (Bailey 2017). Patients aged 65 and over who are involved in significant trauma have a higher risk of complications and higher mortality rates (Rubin 2002; Victorino et al. 2003), with medical, physical, psychological and social challenges and consequences.

Autobiographical memories in ageing

Autobiographical memories enable us to have a past, present, and future in which we exist as individuals: they are one of human beings’ most important bodies of knowledge (Rubin 2002; Robinson 1976; Tulving 2002; Williams, Conway & Cohen 2008). Reminiscence includes the act of recalling and sharing memories of past experiences and events. People treasure their memories, and work to retain them by making scrapbooks, taking photos and sharing them at family gatherings, and so on (Newcombe, Lloyd & Ratliff 2007): this is a normal part of everyday life for older people. Since autobiographical memories contain knowledge about the self and personal identity, this type of memory is highly valued by patients and caregivers; but among older adults — those above the age of 50 — memories from their teens and twenties are somewhat more frequent than are memories from adjacent life periods, though both are still far below recent memories (Rubin 2002; Christiansen & Weppelmann 2011).

Over the last couple of decades, though there has been limited research into the value of reminiscence for older adults in long-term residential care facilities, there have been significant developments in reminiscence techniques and methods for older people more generally (Schweitzer 2016). Researchers have found benefits associated with merely sharing autobiographical memories with others, and disclosing personal information. Benefits include increased empathy, connectedness, intimacy, and self-understanding; enhanced sense of meaning in life; more accessible and more detailed personal memories; reduction in the intensity of emotions for negative events; and positive effects on physical and mental health (Alea & Bluck 2007; Bluck, Baron, Ainsworth, Gesselman & Gold 2013; Collins & Miller 1994; Pasupathi & Carstensen 2003; Skowronski, Gibbons, Vogl & Walker 2004; Ziv-Beiman 2013). So, for many senior citizens, the ability to connect with other people and with their personal past has proven valuable, and reminiscing and reflecting on the past with others serves both physical and psychosocial functions (Henkel, Kris, Birney & Krauss 2017).

But although reminiscence activities may be beneficial for older adults living independently, the same activities may be demoralising for long-term care residents, who have few opportunities to change their lives significantly (Henkel et al. 2017; Hewett, Asamen, Hedgespeth & Dietch 1991). Residents with low mood and symptoms of depression have an increased chance of engaging in unhealthy styles of reminiscence. Likewise, merely evoking feelings of nostalgia, which may occur when reminiscing about the past, can have both positive and negative consequences. Nostalgia can increase feelings of social connectedness and meaningfulness of life, and reduce loneliness and anxiety about death; yet it can also produce an unhealthy emphasis on the past (Hepper, Ritchie, Sedikides & Wildschut 2012; Juhl, Routledge, Arndt, Sedikides & Wildschut 2010; Routledge, Sedikides, Wildschut & Juhl 2013; Wildschut, Sedikides, Routledge, Arndt & Cordaro 2010). Therefore, interventions that shape reminiscence encounters may have positive outcomes for older people (Henkel et al. 2017; Schweitzer 2016); but integrated interventions that shape reminiscence encounters are required for older adults in long-term residential care facilities.

Research shows that residents in long-term residential care facilities preferred to reminisce alone, finding the experience enjoyable; and that they engaged in and enjoyed reminiscence with family more than with fellow residents – though in smaller groups, participants demonstrated increased opportunities to share personal stories. Telling one’s life history and showing the family album can help to form a healthy style of reminiscence, particularly when such stories are shared with others of a similar background: this helps older people gain a strong sense of belonging to a community and having a valued role within it. Pleasurable contact through sharing common memories can thus become the basis for an authentic meaningful friendship between participants in the present (Schweitzer 2016).

The current study highlights the opportunities for technological interventions that better support and encourage older adults living in long-term care facilities to share their past with others. This suggests that there is potential to use low-cost digital design to introduce interventions that can improve both users’ quality of life, and the quality of care they receive. Prior work has shown positive outcomes when nursing staff are involved in reminiscence activities and in getting to know the residents in a more person-centred way (Cooney et al. 2013; Fiske et al. 2009). Sharing one’s memories is beneficial for older adults but more so if they share positive rather than negative experiences (Pasupathi & Carstensen 2003). Storytelling can reduce the power of traumatic memories by focusing on factual details of the event: this reduces the number of intrusive memories that the elderly later experienced (White & Wild 2016). Visual imagery — in this case, family photos — is vital for the symbolic and concrete processing involved in reminiscence, and for revealing and sharing the participants’ autobiographical memories.

Design methods that emphasise empathy and multi-disciplinary participation with key stakeholders

Art and design practice and research have provided new opportunities to work with services and communities, rather than just with commercial products. More and more designers aim to find solutions for complex societal challenges, including health care and aged care (Britton 2017; DiGioia & Shapiro 2017; Picard 2017). Methods such as design thinking and co-design have given not only designers, but also practitioners from other disciplines, tools and methods to observe and tackle the ‘wicked’ problems that we are facing — a new type of late modernity in which social activities interwoven with things and services create value (Armstrong, Bailey, Julier & Kimbell 2014).

Design methods that emphasise holistic, multidisciplinary, and integrative characteristics have become essential strategic means to drive innovation (Yang & Sung 2016). Design thinking has become increasingly popular as a means to address specific business, government and world issues (Peng & Scharoun 2016, 2017; Scharoun & Montana-Hoyos 2017), while co-design — a human-centred approach that involves key stakeholders in the design process to help ensure the result meets the users’ needs and is usable (Britton 2017; Picard 2017; Scharoun & Montana-Hoyos 2017) — offers the likelihood of solving complex social challenges through the combination of multidisciplinary talents and resources with open innovation (Britton 2017; Yang & Sung 2016). The co-design approach is a multi-step ‘solution-focused’ process using user experience, interview and interpretation to solve a known or unknown problem, an approach that emphasises innovative and human-based results rather than results that rely on scientific factors. However, co-design also brings potential risks and costs when it takes place in cross-system and multidisciplinary design processes (Prahalad & Ramaswamy 2004; Leadbeater 1997). Challenges often occur during the multidisciplinary participation processes, because of the mix of stakeholders and ecological systems, diverse viewpoints and backgrounds, and both complexity of interest and lack of efficiency in long-term perspectives (Yang & Sung 2016).

Pilot case study

How do older adults use autobiographical memory to reminisce about their past? And can we combine this use with wearable devices to provide technological intervention and improve older Australians’ wellbeing? The ‘Wearable Memory’ project, which aimed to find answers, was initiated as a part of a grassroots movement – Innovage: innovating aged care solutions. This presents a multidisciplinary approach in a radical co-design format, bringing together key stakeholders — designers, developers, engineers, programmers, business development specialists, and entrepreneurs — to develop both practice and knowledge of technologies, products, services and interventions. As this was a pilot study, we initially chose five participants aged 65 to 80, in long-term residential care at one multicultural care home in the Australian Capital Territory. We included input from the participants’ families and carers: particularly the carers, who had been working with the older adults for more than a year, and knew their daily routines, including their social activities and reminiscence. Over a period of twelve months (March 2016 — March 2017), we went through a multi-step co-design process.

Empathise and define stages: Enhancing participators’ willingness and key-stakeholders’ involvement from the beginning of the projects

Understanding and having empathy, or ‘stepping in the shoes’ of the user is an essential step in the design process (Peng & Scharoun 2016, 2017). The design team visited local nursing homes and aged care centres to work with carers and engage with long-term care residents. Since the co-design process integrates fieldwork with real users through interviews and participant observations, researchers also went to places and spaces, such as shopping malls and museums, which older adults could visit, and where they could identify opportunities and challenges. The relationship between designers and carers is collaborative and usually respectful of local habits and customs. This means the thinking through the entire design process is more fine-tuned and complete, which helps co-design members to understand the demands of service providers and receivers systematically.

The study at the empathise stage identified older adults’ difficulties of social connection in the long-term care facilities. Besides the physical challenges, issues that prevent elderly people from going out and socialising more include emotional and psychological barriers, such as fear of falling and reduced activity level; and their attachment to special artefacts from the past, which they can’t carry with them. We therefore worked together in small groups to explore creative and fun ways to maintain social connections and well-being for this group. The participants were given access to untapped data relating to the sector, as well as products and APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) to play with — 3D printers, VR kits, ibeacons, and face-to-face interaction with real customers, service providers and industry-based mentors — to inform, co-design and test their ideas. To actively involve the older adults so that they would be more likely to accept and fully use the wearable memory system, the researchers and carers prepared digital displays, such as televisions and tablets, in their rooms and common area, and the researchers tailored the Bluetooth device range according to the size of the space.

All the participants believed in the power of art and design, and proposed a wide range of creative media — including artistic self-expression, storytelling, and reminiscence — to deliver design-led innovation and services to the aged care sector. Reminiscence was one of the most mentioned activities. As time passes, many older Australians’ personal stories are forgotten and consigned to dusty photo albums or distant memory. All the participants wished they had taken the time to document a cherished memory of their loved ones and some of their greatest achievements. Most participants, we found, could use a digital family album and liked to receive new photos from their family.

Ideate and prototype stages: Finding appropriate solutions for wicked problems in healthy ageing

After the problems and opportunities had been clearly framed in the empathise and define stages, we brainstormed as many ideas as possible. Significantly more ideas can be generated in the co-design groups than by individuals in a more traditional consultative process (Mitchell, Ross, May, Sims & Parker 2016). The multidisciplinary teams brought in varied perspectives. We also discovered that an emphasis on ‘rapid prototyping’ in the design process was a crucial activity for co-design. Given the limited time and resources available, rapid prototyping is important for the demonstration and interaction of concepts; it uses simple visualised interfaces to reduce costs and help stakeholders evaluate if the concepts are feasible, and where to make modifications (Yang & Sung 2016).

We started by focusing on the devices that older adults have to wear in the facilities, such as their fall detector and call buzzer. The aim was to come up with new designs that combined the function of the current devices while reducing the number of devices they had to wear. Besides the issue of function, we also needed to consider the aesthetics of the devices, and personalise them so that older users would be more willing to wear a device as a piece of ‘jewellery’, and would feel attached to it.

How does it work?

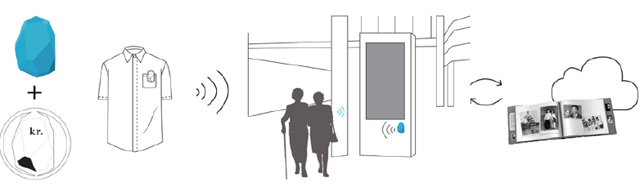

The Wearable Memory is a combination of digital and analogue. The laser-cut objects and Bluetooth devices become featured tangible artefacts, which retain a sensory quality (touch, smell, sight, sound). The design enhances a sense of empathy among elderly people; and the user’s initials were etched in the middle, to give a personal touch. Laser-cut objects were custom made for the Bluetooth devices: Estimote Beacons and Stickers, which have a powerful ARM processor, memory, Bluetooth Smart module, and temperature and motion sensors.

Digital storytelling and social bonding

Through digital storytelling, personal memories can be captured, shared and displayed for the enjoyment and entertainment of family and friends, and also for community members interested in the creative ageing process. Display portals include TV screens at home and in the residential care facilities. Existing displays at shopping centres and public buildings, such as galleries and museums, can also be utilised. Users who carry the device don’t need to press any button to trigger the display or alarm functions. For the pilot study, the designers set the range equal to and less than 0.8m, meaning once the user is within the range, the display portals can play the photo albums automatically. When there is more than one user within range, the portals play the nearest user’s album. Once the user moves out of the range, the portal will stop playing automatically.

Connection + Intervention

One of the disadvantages of reminiscence is that it can produce an unhealthy emphasis on the past that maladaptively undermines current happiness, satisfaction, and wellbeing (van Tilburg, Sedikides, Wildschut & Vingerhoets 2018; Routledge, Sedikides, Wildschut & Juhl 2013; Wildschut, Sedikides & Robertson 2018). The Wearable Memory allows carers and distant family members to interact with older users by constantly feeding visual imagery (in this case family photos) to the Cloud. It can then act as an intervention to promote a healthy reminiscence process that reduces the loneliness and depression associated with social isolation.

Safety + Protection

In addition to storing personal life narrative memories, the design is also a safety device at aged care facilities and home. The Wearable Memory is able to provide important information about the location of the resident, such as sending automated alarms to carers if the resident leaves the facility, or falls. The multiple safety and personalisation features can help reduce the number of safety and identification devices that older people have to wear.

Test stage, and what is beyond? Presenting concepts/solutions and collecting feedback under conditions of limited resources

The project tested the Wearable Memory’s ability to rev up elder users’ memories and the frequency of their social activities in the care facilities and their correspondence with their family. The solutions were judged by a panel consisting of end users, age services and technology experts. When we interviewed key stakeholders in the pilot study, one (anonymous) carer responded:

Having a Wearable Memory helps the senior focus on something other than physical problems and negative preoccupations about loss or aging. Additionally, having a digital family album can create new social connections. It’s not uncommon for one user to stop and talk to another user or carers when their photos are playing on the screen, which can sometimes lead to friendship.

As testing is an opportunity to learn about the solution and users, panel presentations and exhibitions were also adopted as opportunities to collect feedback from local communities and potential stakeholders. The co-designed solutions displayed in a final exhibition at the end of the projects showed insights into the issues, human needs and cultural concerns associated with ageing; and overall, the pilot project proved to be a highly effective means of generating new creative responses.

Although each country has its own unique set of problems, many of the problems they are facing are in relation to the aged populations, and these share common threads. Through our co-design workshops, we attempted to find these common threads and to examine new, cross-cultural and multidisciplinary ways in which we could potentially solve them. This pilot study specifically focused on health technology and service, and how they could be improved or adapted for the elderly. We thought about how the community functioned on a cross-cultural level and how technologies could be used to foster social bonding, not only in Australia but globally.

The Wearable Memory project aimed to make meaningful contributions to the elderly's social reconnection, fall management, and wellbeing. The project team has worked collaboratively to advance design for healthy ageing through design-led innovation to help the transition towards human-centred design solutions in the public and private sectors. One key stakeholder interviewed about the design process commented:

one of the issues that this project might help is around social connectedness. There are many old people who are very well connected to their community, good at technology, understand how to use Facebook, they love all the different ways to be connected to their community and family. Then there are a whole group of people that aren’t connected. This project (Wearable Memory) would be really wonderful and help to trigger some of their memories and be able to help them tell their story. (Kay Richards, National Policy Manager, Leading Age Services Australia Ltd)

Concluding reflections

The findings of the pilot study for this Wearable Memory project reveal that the combination of digital storytelling, reminiscence and autobiography memory is an effective approach with the potential to facilitate positive social connection and bonding for the multicultural community in long-term care facilities. Affordable design and service were created to introduce interventions that can improve residents’ life quality and the quality of care they receive. Moreover, the co-design approach generated from the multidisciplinary design workshops were especially helpful for dealing with the main difficulties involved in older adults’ reminiscence and social isolation, by enhancing participators’ willingness and key-stakeholders’ involvement from the beginning of the projects.

The older adults in the long-term care facilities, and their carers, are important key stakeholders in the co-design process for aged care. They can be creative participants in empathise, define and test stages by allowing them to tell their own stories. Involving older adults’ families through the smartphone application (Wearable Memory) encouraged them to interact with their distant elderly loved ones simply by updating their family album. The visual images gave the older participants opportunities for storytelling, and for refreshing their memories. The Wearable Memory project focused not only on the creation of new products or services, but also on adoption and diffusion of current design products and systems in the long-term care facilities.

The Wearable Memory provided multi-sensory triggers — visuals, sounds and touch — that stimulated participants’ autobiographical memories. Although the participants often preferred to reminisce with family members, the different types of sensory stimulation provided in the common area through the digital display and wearable devices offered a relaxing starting point for participants’ reminiscence and storytelling with others in the same space. When they shared their personal stories with each other in the residential care facilities, a result was that the activities could become the vehicle for new friendships between users in the present.

The co-design process also helped the participants’ family to engage in their reminiscence process from a distance, and provide intervention via feeding new and old photos regularly. The richness of information provided by participants and their family added another layer of insights that encourage the healthy style of reminiscence and social connection. The family photos from the participants’ past helped to reconstruct their life narrative, and this encouraged the participants to share their stories and start conversations with other people – both their carer and other long-term care residents.

Because the Wearable Memory project operated within a community of academics, partners, users, practitioners, carers and aged care providers, it has been framed by an expansive understanding of older adults’ reminiscence and digital storytelling. The pilot study demonstrated impact, and contributed to the knowledge and practice of health technologies, products, services and interventions. It also supported an interdisciplinary philosophy that contributes to healthy ageing, system thinking, and real-world action. This pilot study demonstrates that the Wearable Memory can play an important role in bringing back people’s personal identity and sense of self, while providing intervention towards their reminiscence. These findings suggested that the Wearable Memory has positive outcomes by encouraging older users’ social bonding via digital storytelling, and by reducing boredom, social isolation, and depression in long-term care facilities.

Limiting the pilot study to a single care home is likely to have constrained inputs to the design: extending the project to multiple care homes could achieve more variety of input and more diverse topics, and promote long-term development and the realisation of projects. The inclusion of more homes and places would allow us to reach a wider audience, beyond the local communities. Moreover, as the conclusion of this research was affected by limited time and resources, the study could only provide phased results. Future research is planned with funding already secured for a series of cross-cultural and multi-disciplinary workshops for healthy ageing in Australia and overseas.

Acknowledgment

The author is grateful to all of the participants, universities, and organisations who contributed to this research. This study was undertaken within the design for healthy ageing projects, supported by the Australia Government (via the New Colombo Plan Mobility Funding for Asia Postgraduate Programme, Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade 2015, 2016–19).

Alea, N & S Bluck 2007 ‘I’ll keep you in mind: The intimacy function of autobiographical memory’, Applied cognitive psychology 21.8: 1091–1111

Armstrong, L, J Bailey, G Julier & L Kimbell 2014 ‘Social design futures: HEI research and the AHRC’ [Report], Brighton: University of Brighton

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare 2009 Guidebook for preventing falls and harm from falls in older people: Australian community care, Commonwealth of Australia, https://safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/30455-COMM-Guidebook1.pdf

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2018 ‘Older people: Overview’, Reports and Statistics, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-statistics/population-groups/older-people/overview

Bailey, C 2017 ‘The effects of loneliness and isolation on the elderly’, Lumin 25 June, https://mylumin.org/the-effects-of-loneliness-and-isolation-to-the-elderly

Bluck, S, JM Baron, S Ainsworth, AN Gesselman & KL Gold 2013 ‘Eliciting empathy for adults in chronic pain through autobiographical memory sharing’, Applied cognitive psychology 27.1: 81–90

Britton, GM 2017 Co-design and social innovation: Connections, tensions and opportunities, Melbourne: Routledge

Christiansen, K and S Weppelmann (eds) 2011 The Renaissance portrait: From Donatello to Bellini, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Collins, NL & LC Miller 1994 ‘Self-disclosure and liking: A meta-analytic review’, Psychological bulletin 116.3: 457–75. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.457

Cooney, GM, K Dwan, CA Greig, DA Lawlor, J Rimer, FR Waugh, M McMurdo & GE Mead 2013 ‘Exercise for depression (Review), Cochrane database of systematic reviews 9 (September); doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6

DiGioia, AM & E Shapiro 2017 The patient-centered value system: Transforming healthcare through co-design, Boca Raton: Productivity Press

Fiske, A, JL Wetherell & M Gatz 2009 ‘Depression in older adults’, Annual review of clinical psychology 5: 363–89; doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621

Henkel, LA, A Kris, S Birney & K Krauss 2017 ‘The functions and value of reminiscence for older adults in long-term residential care facilities’, Memory 25.3: 425–35; doi:10.1080/09658211.2016.1182554

Hepper, EG, TD Ritchie, C Sedikides & T Wildschut 2012 ‘Odyssey’s end: Lay conceptions of nostalgia reflect its original Homeric meaning’, Emotion 12.1: 102–19; doi:10.1037/a0025167

Hewett, LJ, JK Asamen, J Hedgespeth & JT Dietch 1991 ‘Group reminiscence with nursing home residents’, Clinical gerontologist: The journal of aging and mental health 10.4: 69–72

Juhl, J, C Routledge, J Arndt, C Sedikides & T Wildschut 2010 ‘Fighting the future with the past: Nostalgia buffers existential threat’, Journal of research in personality 44.3 (June): 309–14; doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2010.02.006

Leadbeater, C 1997 The rise of the social entrepreneur, London: Demos

Mitchell, V, T Ross, A May, R Sims & C Parker 2016 ‘Empirical investigation of the impact of using co-design methods when generating proposals for sustainable travel solutions’, CoDesign 12.4: 205–20; doi: 10.1080/15710882.2015.1091894

Newcombe, N, ME Lloyd & KR Ratliff 2007 ‘Development of episodic and autobiographical memory: A cognitive neuroscience perspective’, Advances in Child Development and Behavior 35: 37–85

Pasupathi, M & LL Carstensen 2003 ‘Age and emotional experience during mutual reminiscing’, Psychology and aging 18.3: 430–42; doi:10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.430

Peng, F & L Scharoun 2016 Cross-Cultural Design, Beijing: Publishing House of Electronics Industry

Peng, F & L Scharoun 2017 ‘Fostering creative competency and value between China and Australia via multi-disciplinary and cross-cultural design workshops’, Australian Council of University Art & Design Schools Conference, Canberra.

Picard, R (ed) 2017 Co-design in living labs for healthcare and independent living: concepts, methods and tools, Milton: Wiley

Prahalad, CK & V Ramaswamy 2004 ‘Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation’, Journal of interactive marketing 18.3: 5–14; doi:10.1002/dir.20015

Robinson, JA 1976 ‘Sampling autobiographical memory’, Cognitive psychology 8.4: 578–95

Routledge, C, C Sedikides, T Wildschut & J Juhl, J 2013 ‘Finding meaning in one’s past: Nostalgia as an existential resource’, in KD Markman, T Proulx & MJ Lindberg (eds), The psychology of meaning, Washington: American Psychological Association, 297–316

Rubin, DC (ed) 2002 Autobiographical memory, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Scharoun, L & CA Montana-Hoyos 2017 ‘The value of co-design across cultures: Engaging students to solve the ‘wicked problems’ of the 21st century’, Australian Council of University Art & Design Schools Conference, Canberra

Schweitzer, P 2016 ‘About reminiscence work’ (personal website),

http://www.pamschweitzer.com/pdf/about-reminiscence-work.pdf

Skowronski, JJ, J Gibbons, R Vogl & WR Walker 2004 ‘The effect of social disclosure on the intensity of affect provoked by autobiographical memories’, Self and identity 3.4: 285–309

Tulving, E 2002 ‘Episodic memory: From mind to brain’, Annual review of psychology 53.1: 1–25

van Tilburg, WAP, C Sedikides, T Wildschutt & A Vingerhoets 2018 ‘How nostalgia infuses life with meaning: From social connectedness to self-continuity’, European journal of social psychology 00: 1–12; doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2519

Victorino, GP, TJ Chong & JD Pal 2003 ‘Trauma in the elderly patient’, Archives of surgery 138.10: 1093–98

White, R, & J Wild 2016 ‘“Why” or “how”: The effect of concrete versus abstract processing on intrusive memories following analogue trauma’, Behavior therapy 47.3: 404–15; doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.02.004

Wildschut, T, C Sedikides & S Robertson 2018 ‘Sociality and intergenerational transfer of older adults’ nostalgia’, Memory 26.8 (September): 1030–41; doi: 10.1080/09658211.2018.1470645

Wildschut, T, C Sedikides, C Routledge, J Arndt & F Cordaro 2010 ‘Nostalgia as a repository of social connectedness: The role of attachment-related avoidance’, Journal of personality and social psychology 98.4: 573–86; doi:10.1037/a0017597

Williams, HL, MA Conway &G Cohen 2008 ‘Autobiographical memory’, in G Cohen & MA Conway (eds), Memory in the real world (3rd ed.) London: Psychology Press, 21–90

Yang, C-F & T-J Sung 2016 ‘Service design for social innovation through participatory action research’, International journal of design 10.1: 21–36

Ziv-Beiman, S 2013 ‘Therapist self-disclosure as an integrative intervention’, Journal of Psychotherapy Integration 23.1: 59–74