When my love swears that she is made of truth

I do believe her though I know she lies,

That she might think me some untutored youth

Unlearned in the world’s false subtleties.

Thus vainly thinking that she things me young,

Although she knows my days are past the best,

Simply I credit her false-speaking tongue;

On both sides thus is simple truth suppressed.

But wherefore says she not she is unjust,

And wherefore say not I that I am old?

O, love’s best habit is in seeming trust,

And age in love loves not to have years told.

Therefore I lie with her, and she with me,

And in our faults by lies we flattered be.

—William Shakespeare, Sonnet 138 (1608)

Introduction

It is important at the outset to clarify the nature of my project. This research has been produced to support the development of a historical fiction work. I am not trying to write a thesis but to collate fragments of ideas that can feed into my creative piece, a historical fiction novel. The central characters of my novel are the embodiment of ‘carnival’, the dishonest woman and the cuckold man as inspired by works of Peter Bruegel the Elder. I have chosen these, as representations of women and men of this period and place, for particular reasons. My interest began with depictions of Carnival in art and literature in the sixteenth century and in many ways these two characters typify much that Carnival presented. I shall explore what I mean by this shortly.

To discover more about Carnival I make use of Bakhtin’s definition of ‘folk culture’ covering the various elements of human existence such as public demeanour, food, drink, death, sex and the renewal of life, which official culture usually keeps temporally and spatially separate in relation to Bruegel’s painting.

Bruegel’s The Nederlandish Proverbs (also referred to as The Topsy-Turvy World and The Blue Cloak), depicts common Flemish folk going about their everyday lives. On initial inspection, people are performing daily activities, sometimes in a chaotic fashion, but they are working, gossiping and tending to animals. But the more I observed this painting, and with the help of a small book on Dutch proverbs [3], the more there was to discover. The painting contains over 120 proverbs, some still in use today in the Dutch language and in English translations. A selection of these is included below, with numbered links in the picture.

From De Nederlandse Spreekwoorden

1.

Bare-bottomed knave who sullies the globe (To despise everything)

Bare-bottomed knave who sullies the globe (To despise everything)

To lead each other by the nose (To fool each other)

To lead each other by the nose (To fool each other)

Fools get the best cards (Luck can over come intelligence)

Fools get the best cards (Luck can over come intelligence)

2.

To toss feathers in the wind (To work fruitlessly)

To toss feathers in the wind (To work fruitlessly)

3.

To have the roof tiled of tarts (To be very wealthy)

To have the roof tiled of tarts (To be very wealthy)

4.

To be barely able to reach one loaf to another (Difficulty living within a budget)

To be barely able to reach one loaf to another (Difficulty living within a budget)

5.

Spilt porridge cannot be scraped up (Something cannot be undone)

Spilt porridge cannot be scraped up (Something cannot be undone)

6.

One shears sheep, the other pigs (One has all the advantages, the other none)

One shears sheep, the other pigs (One has all the advantages, the other none)

To bang your head into a wall (Trying to achieve the impossible)

To bang your head into a wall (Trying to achieve the impossible)

One foot wears a shoe, the other is bare (Balance is paramount)

To bell the cat (To carry out a dangerous/impractical plan)

To bell the cat (To carry out a dangerous/impractical plan)

7.

To fall from the ox onto the rear end of an ass (To fall on hard times)

To fall from the ox onto the rear end of an ass (To fall on hard times)

To wipe ones backside on the door (To treat something lightly)

To wipe ones backside on the door (To treat something lightly)

But it was the discovery of the proverb behind two seemingly innocuous characters in the middle of the painting that was to excite me the most. Central to the painting, and extracted in the image on this page, is a young woman dressed in a low cut red gown, draping a blue cloak over a man.

Based on the proverb below, it seems reasonable to assume they are a married couple. His cloak is unusual because of the bright shade of blue, but it also inhibits his vision. He appears, from his face and walking stick, to be much older than his wife.

Het bijbelehorende spreekwoord zegt: “Zij hangt haar man de blauwe huik om, zij bedriegt hem. De blaue huik is in Nederland her symbol van echtelijke ontrouw.” [4]

Roughly translated:

She hangs over her husband the blue cloak, deceiving him. The blue cloak is the symbol of marital infidelity in the Netherlands.

In much the same way as Peter Stallybrass and Allon White describe in their study of the grotesque and carnivalesque, ‘what is socially peripheral is so frequently symbolically central’ [5], I began to wonder if an understanding of the cuckold man and dishonest woman might also provide insight into aspects of the society, on which I could build a novel sized story.

As I continued to research Bruegel’s work, I was to discover my two main characters playing more than a peripheral role. The theme of cuckoldry would appear in other paintings, often taking me by surprise. What began as a way of understanding people of centuries past turned into a journey of discovery. By considering depictions in literature and art, including Bruegel and other artists, it emerged as a way for me to bring alive, in narrative form, depictions of people from times past.

My interest in the dishonest woman and cuckold man moved beyond being simply typical characters of Carnival, to representations of men and women and their interrelations in a specific period of time. I also wanted to consider if they might be a result of each other and the patriarchal society of the time.

In the second half of the 16th century Peter Bruegel the Elder painted numerous Carnival scenes. In Figure 2 we see common folk celebrating, playing music, dancing, drinking, even stealing a brief kiss. He portrays everyday people in all their detail, at times harsh and not always attractive; people are depicted enjoying themselves. Scenes are filled with immense activity; life is complex and chaotic. In embarking on my novel, I began to see my narrative unfolding. I would bring to life, in words rather than images, the characters portrayed in Bruegel’s work.

One of the early questions I encountered was, what is the connection between the cuckold man and the dishonest women, and Carnival? While the cuckold man could have been a caricature of the Carnival spectacle, where his situation was exposed for the mock and ridicule of his neighbours, I was more interested in parallels that can be drawn.

Applying the Carnival concept of renewal and rebirth to the idea of cuckoldry raises some intriguing ideas. In interpreting the concept of renewal as ‘out with the old and in with the new’, the young wife is uncrowning her old husband and there is a new act of procreation with her young lover. Bakhtin describes the importance of the cuckold in the symbolic code of carnival, that ‘the cuckolded husband assumes the role of uncrowned old age, of the old year, and the receding winter. He is stripped of his robes, mocked and beaten.’ [6]

The connection between the dishonest women and Carnival is more complicated. Bakhtin has been referred to as silent on feminist issues in his work but in The Last Laugh: Carnivalizing the Feminine in Piron’s ‘LaPuce’ Sharon Nell considers that Bakhtin’s exclusion of the feminine is illusory:

Woman, ‘the outside’, is ‘inside’ because of the intimate connection Bakhtin makes between the female body and carnival (Derrida 1976: 44-65) … By locating at the very beginning of his list two images attributed exclusively to the female body (pregnancy and birth), Bakhtin identifies Woman with the grotesque. In this level, the female body is a place of carnival. [7]

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Bakhtin compares the grotesqueness of the ‘old hag’ to Kerch terracotta images:

In the famous Kerch terracotta collection we find figurines of senile pregnant hags. Moreover, the old hags are laughing. This is a typical and very strongly expressed grotesque. It is ambivalent. It is pregnant death, a death that gives birth. There is nothing completed, nothing calm and stable in the bodies of these old hags. They combine a senile, decaying and deformed flesh with the flesh of new life, conceived but as yet unformed. Life is shown in its two-fold contradictory process; it is the epitome of incompleteness. And such is the grotesque concept of the body. [8]

Mary Russo (1986) discusses women’s behaviour and particularly the idea of a woman ‘making a spectacle out of herself’ and it being a specifically feminine danger. When a woman makes a spectacle of herself there is a loss of boundaries, an inadvertency. [9] She describes how such a woman, in making a spectacle of herself, is considered to be doing something inappropriate; that she had stepped into the limelight and opened herself up to ridicule, that she was too young, too old, too early, too late etc. and her behaviour was improper. Russo further states that:

there is a way in which radical negation, silence, withdrawal, and the bold affirmations of feminine performance, imposture, and masquerade (purity and danger) have suggested cultural politics for women. [10]

Natalie (1965) argues that in early modern Europe, Carnival and the image of the carnivalesque woman ‘undermined as well as reinforced’ the renewal of existing social structures.

The image of the disorderly woman did not always function to keep women in their place. On the contrary, it was a multivalent image that could operate, first, to widen behavioral options for women within and even outside marriage, and second, to sanction riot and political disobedience for both men and women in a society that allow the lower orders few formal means of protest. [11]

In considering the sixteenth century woman, and in particular how to portray such a character in a novel, I was interested in her place in her society and the potential repercussions of this. As Russo highlights, the marginalised position of women in the ‘indicative’ world makes their presence in the ‘subjective’ world of the topsy-turvy carnival as quintessentially dangerous. [12] And as Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie shows in Carnival at Romans, there is evidence that women were raped during carnival events [13], which I guess shouldn’t be a surprise.

Stallybrass and White refer to the exclusion of the already marginalised as ‘displaced abjection’ and that ‘Carnival often violently abuses and demonizes the weaker, not stronger, social groups – women, ethnic and religious minorities, those who don’t belong.’ [14] They further give the example of displaced abjection where the pig is celebrated and describe the process whereby low social groups turn their figurative and actual power, not against those in authority, but against those who are considered even lower, such as women, Jews, animals, cats and pigs.

The dynamics of social hierarchy appear as an aspect of Carnival, where those at the ‘top’ of the structure attempt to reject or eliminate those at the ‘bottom’. While the reasons for the displacement are often prestige or status, those at the top discover that they are dependent upon the low, or Other. Stallybrass and White describe this as a psychological dependence upon the Other, [15] which I will now look at as a gender issue.

The concept of the dishonest woman began long before the sixteenth century. In the Bible, Eve is deceived by the serpent and leads Adam astray. In Greek mythology [16], Roman literature and medieval texts [17] there are examples of women portrayed as carnal and lustful while men are spiritual, the victims of temptation. By the Middle Ages the church is portraying Eve as responsible for the fall of mankind. Women were associated with sexuality and sin, and sin could only be avoided through chaste living. Sources are not difficult to find, from St Jerome (C 320-42) ‘Woman is the root of all evil’ to the ballad, ‘The Cucking of a Scold’ (1615).

The Cucking of a Scold

Then was the Scold herself,

In a wheelbarrow brought,

Stripped naked to the smock,

As in that case she ought:

Neats tongues about her neck

Were hung in open show;

And thus unto the cucking stool

This famous scold did go.

By the sixteenth century, there is the strong image of the untrustworthy woman, long established in literature (primarily written by men). The beliefs of the church still had a firm hold and men were advised to aspire to honour and esteem and be wary of the opposite sex.

The Education or Instruction of a Christian Woman is an early sixteenth-century book by Juan Luis Vives, written for the education of the future Mary I of England, daughter of Henry VIII. The manual was praised by Erasmus and Thomas More, and advocated education for all women, regardless of social class and ability and provided practical advice for women from raising girl infants, suitable literature and interests, to being a good wife. Vives argued that women were intellectually equal if not superior to men, and stressed intellectual companionship in marriage over procreation, and moved beyond the private sphere to show how women's progress was essential for the good of society and state. He describes woman as ‘a weak creature and of uncertain judgement ... easily deceived (as Eve, the first parent of mankind, demonstrated, whom the devil deluded and with such a slight pretext)’ [21]. He further asserted that a woman’s virginity is her most precious commodity, representing not simply a body free from corruption or contamination, but integrity of mind.

Virtuous women from history were portrayed as having three prominent qualities: fortitude, wisdom and virginity. Diana, from Roman mythology, the goddess of the hunt, the moon and nature, was also known as the virgin goddess of childbirth and women. ‘So much admiration does virginity elicit that lions stand in awe of it.’ (Saint Ambrose). It is therefore a reasonable assumption that a woman, up to and during the sixteenth century (and for some time beyond) was not required to be eloquent, talented, have wisdom or any professional skills. She had but one thing of value: her virginity and therefore her chastity. A woman was advised to keep her bed clean but not luxurious, so that she may sleep peacefully but not sensually. Her clothes should be neat and spotless but neither too expensive nor ornate.

In the midst of pleasures, banquets, dances, laughter, and self-indulgence, Venus and her son Cupid reign supreme. Such things attract and ensnare human minds, but especially those of women, over which pleasure exercises an uncontrolled tyranny.

Chapter XIII On Love Affairs, The Education of a Christian Woman

However, there is also evidence to suggest that not all men and women in medieval times had such views. There was the paradoxical argument that while women might be ‘the gateway of the devil’, in the case of the virtuous and virginal woman, she was also ‘the bride of Christ’.

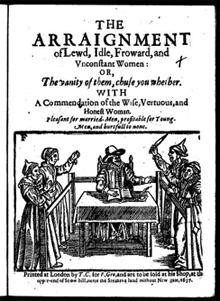

Joseph Swetnam advised men in Arraignment of Lewd, idle, forward, and unconstant women (1615):

For women have a thousand ways to entice thee and ten thousand ways to deceive thee…. They lay out the folds of their hair to entangle men into their love; betwixt their breasts in the value of destruction; and in their beds there is hell, sorrow and repentance. [22]

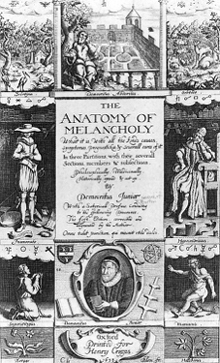

In a similar guide for potential husbands, Robert Burton in The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) advises men that ‘All women are slippery, and often unfaithful to their husbands.’ [23]

During the sixteenth century, we witness a shift in the nature of power and governing, as Foucault describes it; a series of treatises on the ‘art of government’ began to appear. The scope of these was much wider than in previous periods, where the focus was primarily on guarding power and the nature of the state. Now the state was interested in ‘governing a household, souls, children, a province, a convent, a religious order, or a family’ [24]. There is a major shift from concerns of the nature of the state to a more detailed consideration of how to introduce economy and order from the top of the state down through all aspects of social life.

Rabelais' tale of Panurge’s quest for a faithful marriage partner in Tiers Livre (1546) is an example of ‘unquestionable hysteria on the part of this male figure since it was generally thought that women were naturally prone to deception because of their uncontrollable libidinal energy.’ [25]

I was intrigued how this portrayal of women and men may have helped foster a genuine fear in men that women could not be trusted and that they were at serious risk of being cuckolded. The term cuckold is derived from the cuckoo bird, which is known to lay its eggs in the nests of other birds. It first appeared in use in the English language around 1250 in the satirical poem ‘The Owl and the Nightingale’, and the Owl states that the Nightingale’s gay melodies can entice women to adultery and promiscuity. To be cuckolded is to be deceived. The cuckold husband could be unaware of his wife's unfaithfulness and may not find out until the arrival of a child that was plainly not his, such as with cuckoo birds. It seems ironic that, in a patriarchal society where a man is deemed superior to a woman, he should be beholden to her, with her supposed voracious sexual appetite and propensity to tell lies, to achieve that which he often desired, an heir. And therein lies the dilemma in representing for 16th century man in literary form.

For Adam was created first, then Eve, and Adam was not seduced but the woman was seduced and led astray. —Apostle Paul, writing to his disciple Timothy

… a ploy to ruin a man’s health and drain him of his vitality —Jean de Marconville, De l’heur et Malheur du marriage

An image was beginning to emerge. Was a man confronted with the dilemma of having to find a suitable wife and partner, yet struggling against an ingrained belief that women simply could not be trusted? Perhaps even worse, driven by uncontrollable libidinal energy? Were women the lascivious corruptors of men?

There is certainly evidence in literature, primarily written by men of the period for men, that women were so inclined. Aristotle in History of Animals (4th century BC) advises parents to ‘keep special watch over their daughters at the beginning of puberty and keep them away from all contact with men. During that period, they are more inclined to lust.’ Roman women were encouraged to drink only a little beer or wine for digestion, but not to inflame the body (Valerius Maximus), as it was considered good for restraining sexual passion, lust, and wantonness of the body. The Widow of Ephesus, an inset tale of Satyricon (chapters 111-112), written in the first century AD, depicts a corrupt society dominated by the desire for sensual fulfillment. The tale is narrated by the decrepit poet/raconteur, Eumolpus, to expose ‘female fickleness’ by illustrating that ‘no woman is so chaste that she might not be turned to fury by a foreign love.’

As with Rabelais’ character, Panurge struggled to decide whether to get married; women provided quite a dilemma for an honourable man. While a wife provided the key to producing children and thereby establishing the man’s honour, she was an untrustworthy creature, with insatiable sexual drives, given to ruining his health and taking away his masculinity. Panurge is an interesting example of a man trying to decide between a desire for marriage and the fear of the consequences, the very real danger of being cuckolded. Kritzman describes ‘the menace of female sexuality, a phenomenon which ultimately threatens the phallocentric figure with the imaginary loss of its being.’ [26] Rabelais portrays the female as ‘fated to the demands of an uncontrollable jouissance (French, enjoyment with a sexual connotation)’ [27]. However, the male character projects profound sexual anxiety. Which brings us to the concept of cuckoldry and the fear of being cuckolded.

cuckoldry anxiety rehearses a play that may never be performed since it is largely a projection of the husband’s own fears translated into a story about his wife’s inevitable infidelity or concupiscence. [28]

To fear that your partner is or may be unfaithful is not a concept unique to the sixteenth century. However, to fully appreciate what this fear may have meant for men of this time, the repercussions for women, and how these might be incorporated into a work of historical fiction, I wanted to consider the concept within the context of society, its norms and expectations.

Breitenberg describes the ‘Renaissance Man’ with cultural anxieties implanted in the male body, and the fear eventually culminating with the fantasy of reversal, that a man could turn into—or be turned into—a woman, [29] and this idea appealed to me.

Foucault later noted that: ‘The Middle Ages had organized around the theme of the flesh and the practice of penance a discourse that was markedly unitary.’ [30] It is a time when the Church is a single supreme power and the ‘confession’ a key component of this. In his subsequent publication, Foucault goes on to say:

Christianity associated it [sexuality] with evil, sin, the Fall, and death, whereas antiquity invested it with positive symbolic values. Or the definition of the legitimate partner: it would appear that, in contrast to what occurred in the Greek and Roman societies, Christianity drew the line at monogamous marriage and laid down the principle of exclusively procreative ends within that conjugal relationship. [31]

Foucault subsequently observes that while the men of ancient times were rather indifferent to the nature of the sexual act, monogamous fidelity, homosexual relations and chastity, at the point of the Middle Ages, these points (and the governance of these) were becoming of much importance.

Guazzo describes The Court of Good Counsel (1607), ‘Wherein is set down the true rules how a man should choose a good wife from a bad, and a woman a good Husband from a bad’, and goes on to say, ‘There is no greater plague, nor torment … than to be matched with an untoward, wicked and dishonest woman.’

In aspiring not to be ‘women’, men also had to ensure they did not behave in a female manner or, taking this to a further degree, even have feminine desires. While women were considered preoccupied with the frivolous and vain [34], men were encouraged to suppress such feminine whims in order to become real men.

Interestingly, although male on male sodomy was condemned by the Church [35] as an act contrary to nature and impeding procreation, it was not the act itself that was publicly criticised. [36] Of more concern was the fact that one of the men had voluntarily demoted himself to a subordinate role, and one that should have been assumed by a woman.

A man established his authority through guiding and protecting those inferior to him, namely his wife, his family and lower status men. Preachers recognised this paternal authority and advised women to go to their husbands for spiritual counsel, claiming it would be ‘pleasing to God’. [37] A proper Christian prince should be ‘like a father to the state’, guiding his subjects and protecting them from harm. [38] For women female chastity was commended and considered the cornerstone of feminine reputation. Christine de Pizan, while advocating for equality of the sexes in the Querelle de Femmes debate, also contended that chastity was the supreme virtue in women. [39] Marriage and procreation provided men with the means to establish their masculinity. Valeria Funucci argues that masculinity was realised in a man’s ability to ‘confirm his manhood through offspring’ [40]. Therefore, we can begin to establish that a man could demonstrate his virility morally through legitimate marriage, thereby increasing his honour. With such an importance placed on fatherhood, the ideals of family and marriage rose as social norms. Meanwhile a wife should strive to ‘bear him children worthy of both parents and of their country’ [41]. With this in mind, the task of choosing a suitable wife was not an easy one. Guazzo stated that when a man chooses a wife, ‘he ought to marry while he himselfe is young... for both being young, they are likelier to have children.’

When Guazzo is asked during his conversation, ‘whereof commeth that common distrust that menne haue in their wives?’ he replies, ‘Perchaunce of the fragilitie and weaknesse of the flesh, which is attributed to most women’.

This indicates how common the distrust was. Whether he has actually been cuckolded or not is not so much the issue here, rather the fear that he might be.

The Anatomy of Melancholy [42] (1621) by Robert Burton is presented as a medical textbook on melancholia (now termed clinical depression). In section MEMB. IV. SUBSECT I. Burton addresses ‘the Cure of Jealousy; by avoiding occasions, not to be idle: of good counsel; to contemn it, not to watch or lock them up: to dissemble it. &c.’. Burton describes male jealousy and the fear of being cuckolded as one of the most disabling symptoms of melancholic. In one account, a baker is so obsessed with the prospect of his wife’s adultery that he ‘gelded himself to [her] try honesty’. Breitenberg makes a connection here between gelding (meaning to castrate) and that the baker’s fear is literally castrating him. He also provides an alternative reading that the baker’s wife has the power to remove his virility if she commits adultery. [43] Either reading demonstrates the fear of being cuckolded held over men.

In Shakespeare’s play, Iago plays on Othello’s fear that Desdemona is cuckolding him with the young and handsome Michael Cassio. Ironically, Iago himself expresses the worry that he may have been cuckolded by Othello (with Iago’s wife, Emilia).

Who dotes, yet doubts, suspects, yet strongly loves! —Othello, Act 3, Scene 3

Who would not make her husband a cuckold to make him a monarch [if cuckolding him meant giving him command of the whole world] —Othello Act 4, Scene 4

But there is another issue to be regarded. I opened this paper with Shakespeare’s Sonnet 138, which closes with the line, ‘Therefore I lie with her…’, which brings me to the issue of the contented cuckold, or wittol. The Oxford English Dictionary defines a wittol as ‘A man who is aware of and complaisant about the infidelity of his wife’.

Coppélia Kahn notes that the epithet wittol ‘singles out one aspect of the cuckold’s situation for special ridicule; he who knows his wife untrue and doesn’t take action against her is indeed less than a man.’ [44]

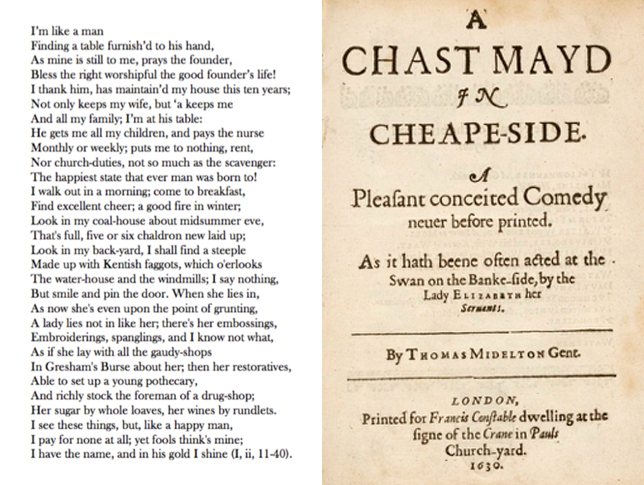

Jennifer Panek, in her paper, ‘A Wittall cannot be a cookold’, considers whether an early seventeenth century audience would have necessarily regarded the wittol with automatic, unmitigated contempt. In considering the wittol as portrayed in literature of the period, we see an interesting character. While the cuckold is often portrayed as the unhappy, deceived fool, with the wittol we see a different perspective. The wittol benefits from the situation, as can be seen in Middleton’s comedy, Chaste Maid in Cheapside, listed above. Panek argues that:

Middleton creates an outrageous wish-fulfillment fantasy figure that promises all the privileges of patriarchal domestic order with none of their attendant anxieties, and that, precisely due to this lack of symmetry between male privilege and responsibilities, holds considerable subversive potential. [45]

In conclusion

As I stated at the beginning of this paper, my intention was not to study the dishonest women and cuckold man in depth, but to consider them from the perspective of a writer and how I could bring them to life in a fictional novel. I have considered Bruegel’s paintings and to this end his work has revealed two complex characters as well as saying much about the relationship between men and women during the sixteenth century. Bruegel’s depictions are intricate and revealing, and I hope that the characters within my novel might achieve something similar, in much the same way as other artists have replicated his work for many hundreds of years. But as expected, these things are never simple.

Notes

[1] Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall, (New York: St Martin’s Press, 2010)

[2] Tracy Chevalier, Girl with a Pearl Earring, (London: HarperCollins Publishers, 2000)

[3] Gerdy Seegers, Pieter Bruegel de Oudere, De Nederlandse Spreekwoorden, (Amersfoort: Bekking & Blitz B.V., 2011)

[4] Gerdy Seegers, Pieter Bruegel de Oudere, De Nederlandse Spreekwoorden, p.89

[5] Peter Stallybrass and Allon White, Politics and Poetics of Transgression (London: Routledge, 1986) page 23

[6] M. M. Bakhtin and Helene Iswolsky, Rabelais and His World, 8th ed., p.241

[7] Sharon Diane Nell, The Last Laugh: Carnivalizing the Feminine in Piron’s ‘LaPuce’, p.1

[8] M. M. Bakhtin and Helene Iswolsky, Rabelais and His World, 8th ed., pp.25-26

[9] Mary Russo, ‘Female Grotesques, Carnival and Theory’ in Teresa De Lauretis (ed.) Feminist Studies/Critical Studies (4th edn) (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986) p.213

[10] Mary Russo, ‘Female Grotesques, Carnival and Theory’ in Teresa De Lauretis (ed.) Feminist Studies/Critical Studies (4th edn) (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986) p.213

[11] Natalie Davies, ‘Women on Top’ in Society and Culture in Early Modern France (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1965), p.131

[12] Mary Russo, ‘Female Grotesques, Carnival and Theory’ in Teresa De Lauretis (ed.) Feminist Studies/Critical Studies (4th edn) (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986) p.217

[13] Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, Carnival at Romans, trans. Mary Fenneg (New York, NY: Braziller, 1979)

[14] Peter Stallybrass and Allon White, Politics and Poetics of Transgression, page 19

[15] Peter Stallybrass and Allon White, Politics and Poetics of Transgression, page 5

[16] For example, Hephaestus walked into his bedroom to find his wife, Aphrodite, and her lover, Ares, in bed, naked, trapped under a net.

[17] John Lydgate, ‘Fall of Princes’ (c. 1440); Geoffrey Chaucer ‘The Miller's Tale’ (c. 1390)

[18] De Cultu Feminarum, section I.I, part 2 (trans. C.W. Marx)

[19] De miseria humanae conditionis (On the Misery of the Human Condition)

[20] Mark Breitenberg and Stephen Orgel, Anxious Masculinity in Early Modern England, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996) p.20

[21] Juan Luis Vives, The Education of a Christian Woman: A Sixteenth-Century Manual

[22] Joseph Swetnam, Arraignment of Lewd, idle, forward, and unconstant women, p.7

[23] Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy (829:III, 3)

[24] Michel Foucault, ‘On Governmentality’ (1978), Ideology & Consciousness No. 6 (Autumn 1979) pp.8-10

[25] Lawrence D. Kritzman, The Rhetoric of Sexuality and the Literature of the French Renaissance, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), p.30

[26] Lawrence Kritzman, The Rhetoric of Sexuality and the Literature of the French Renaissance, p.31

[27] Lawrence Kritzman, The Rhetoric of Sexuality and the Literature of the French Renaissance, p.32

[28] Mark Breitenberg and Stephen Orgel, Anxious Masculinity in Early Modern England, p.5

[28] Mark Breitenberg and Stephen Orgel, Anxious Masculinity in Early Modern England, p.7

[30] Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: The Will to Knowledge: V. 1 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1998) p.33

[31] Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: The use of pleasure: V. 2 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1992) p.14

[32] Baldesar Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, trans. George Bull (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1967), pp.211

[33] Giovanni Della Casa, Galateo: Of Manners & Behaviors, ed. L Einstein (Boston, MA: The Merrymount Press, 1914), pp.104

[34] Anne Borelli and Maria Pastore Passaro, ed. and trans., Selected Writings of Girolamo Savonarola (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006), pp.147

[35] Martin Luther's view of homosexuality is recorded in Plass's What Luther Says: ‘The vice of the Sodomites is an unparalleled enormity. It departs from the natural passion and desire, planted into nature by God, according to which the male has a passionate desire for the female. Sodomy craves what is entirely contrary to nature. Whence comes this perversion? Without a doubt it comes from the devil.’

[36] Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), pp.3, 13

[37] Konrad Eisenbichler, trans., Girolamo Savonarola: A Guide to Righteous Living and Other Works (Toronto: CRRS Publications, 2003), pp.59

[38] Desiderius Erasmus, The Education of a Christian Prince, trans. Lisa Jardine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), pp.17

[39] Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, trans. Earl Jeffrey Richards, rev. ed. (New York: Persea Books, 1998), pp.155

[40] Valeria Finucci, The Manly Masquerade: Masculinity, Paternity, and Castration in the Italian Renaissance (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), pp.106-107

[41] Erasmus, Christian Prince, 96

[42] full title: The Anatomy of Melancholy, What it is: With all the Kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it. In Three Maine Partitions with their several Sections, Members, and Subsections. Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically, Opened and Cut Up

[43] Mark Breitenburg, Anxious Masculinity in early Modern England, pp.16

[44] Coppélia Kahn, Man’s Estate, p.129

[45] Jennifer Panek, ‘A Wittall cannot be a cookold’: Reading the Contended Cuckold in Early Modern English Drama and Culture

Beaumont, M and Pater, W 2010 Studies in the history of the renaissance, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Berrong, R 1986 Rabelais and Bakhtin, popular culture in Gargantua and Pantagruel, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press

Brown, A 1999 The renaissance (2nd edn), New York, NY: Longman

Burke, P 1997 The renaissance (studies in European history) 2nd edn), Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Burke, P 2009 Popular culture in early modern Europe, Farnham: Ashgate Publishing

Castle, T 1987 Masquerade and Civilization: The Carnivalesque in eighteenth-century English culture and fiction, Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press

Clarke, L 2010 The chymical wedding, Richmond: Alma

Davis, N 1987 Society and culture in early modern France, Cambridge: Polity

De Lauretis, T 1986 Feminist studies/critical studies (4th edn.), Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press

Dello Russo, W 2012 Bruegel, Munich: Prestel

Eagleton, T 2005 The function of criticism, London: Verso Books

Foucault, M 1992 The history of sexuality: The use of pleasure: V. 2: The use of pleasure, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books

Foucault, M 1998 The history of sexuality: The will to knowledge: V. 1: The will to knowledge, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books

Gibson, M 2012 The Mill and the Cross: A commentary on Peter Bruegel's way to Calvary, London: University of Levana Press

Goldstein, C 2013 Pieter Bruegel and the culture of the early modern dinner party, Burlington: Ashgate

Hirschkop, K and Shepherd, D 2001 Bakhtin and cultural theory, (2nd edn), Manchester: Distributed exclusively in the US by Palgrave

Holquist, M 1990 Dialogism: Bakhtin and his world, New York: Routledge

Iswolsky, H and Bakhtin, M 1984 Rabelais and his world (8th ed.), Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press

Knowles, R 1998 Shakespeare and carnival: After Bakhtin. Basingstoke: Macmillan Publishers

Kritzman, L 1994 The rhetoric of sexuality and the literature of the french renaissance. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press

Lammertse, F and Van der Coelen, P (n.d.) De ontdekking van het dagelijks leven van Bosch tot Bruegel, Museum boijmans

Murray, J 1972 Antwerp in the age of Plantin and Brueghel, London: David & Charles PLC

Orrock A 2017 Bruegel Defining a Dynasty, London/New York: Philip Wilson Publishers

Orgel, S and Breitenberg, M 1996 Anxious masculinity in early modern England. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press

Peakman, J et al. 2011 A cultural history of sexuality, Oxford: Berg

Platter, C et al. 2001 Carnivalizing difference: Bakhtin and the other, London: Routledge

Rabelais, F and Cohen, J 1972 Gargantua and Pantagruel: The histories of Gargantua and Pantagruel (classics). Baltimore: Penguin Classics

Rietbergen, P and Seegers, G 2007 Pieter Bruegel de Oudere (1525/30-1569): De Nederlandse spreekwoorden. Amersfoort [etc.]: Bekking & Blitz

Russo, M 1995 The female grotesque: Risk, excess and modernity, New York: Routledge

van Mander, K 1604 Het SchilderBoeck, electronic download, 2/2/2017

Vice, S 1997 Introducing Bakhtin, Manchester: Manchester University Press, Distributed exclusively in the USA by St Martin's Press

Vives, J 2000 The education of a Christian Woman: A sixteenth-century manual. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press

White, A and Stallybrass, P 1986 The politics and poetics of transgression, London: Routledge

Will, C 2008 Jeroen Bosch: Tussen hemel & hel. Amsterdam: Stokerkade cultuurhistorische uitgeverij

Zophy, J 1998 Short history of renaissance and reformation Europe (2nd ed.), London: Pearson Education