Michael Bakhtin describes the carnival of the Middle Ages as celebrating temporary liberation from prevailing truth and established order, where everyone was considered equal. And as a metaphor for a world upside down, topsy-turvy and disorderly in a search for equality and order, it fits the world of story narratives well. From Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night through Henry James’ Turn of the Screw and beyond, we can see the ideas of ‘equality’ being played with. One of the most prevalent ‘temporary liberation’ ideas of the twenty-first century is the plight of ‘forced migrants’. It’s not a new idea; ancient stories highlight the successes. The Old Testament gives us two popular examples: Moses in the basket and Joseph’s deliverance from slavery. Both are small footnotes in the larger stories they depict, though appropriate nevertheless. But, of course, these success stories have long been overshadowed by centuries of diaspora caused by war, famine and economic circumstances, where millions of the world’s population are continually looking for a better life. It’s a carnivalesque of fortune, where the escape (from war or famine, say) comes to be met by other forces. Witness the forced internment of ‘forced migrants’ on Manus island, the thousands of ‘forced migrants’ drowning in the Mediterranean Sea trying to cross into Europe, and those in camps and temporary holding locations for ‘forced migrants’ who can’t move on and can’t move back, stuck in a perpetual traffic jam of people looking for a better life. And we can see the narrative that surrounds the humanity of such people as they move from being refugees to boat people to forced migrants; the UK Prime Minister, David Cameron, called them a ‘swarm’ as recent as 2015. Whatever collective nouns we choose for them, it is a carnival of chaos and their temporary liberation as ‘forced migrants’ is indeed fleeting, declaring that everyone is most certainly not considered equal.

Recently, the artist Stephanie Morris and I began collaborating on ways to create a shift in the perception of forced migrants, through word and image, for children, in a picture book entitled The Boat (see http://the-immigration-boat-story.com/ and https://vimeo.com/245075528 Password: KingLouis). We did so because children are constantly bombarded with images of the plight of these unfortunate people, and worse, such as those of Aylan Kurdi, the three-year-old Syrian boy lying dead on a Dalaman beach. There is no nine o’clock watershed on televisual news, internet searches and the like. Thus, we felt that children deserve and need a different kind of exposure to the issues. The book involves a ‘dialogue’ with children on the problems raised by taking a story of a child being taken onto a boat, as the boat and its occupants go in search of a better life—of which there are no promises.

We reasoned that while children may view the world from a different viewpoint to their adult counterparts, as defined by age and experience, the astonishment and amazement at witnessing or hearing about the ongoing experience of sheer existence is a defining challenge. The Boat sets out to address the experiential difference between the parent/reader through words and images. For a child, the book—the text, the story—stands as a mediator between experience and inexperience, as representing an arrested moment in experiencing something new that will not stand still, for it will never be new again, but will always be, Penelope-like, starting over. Just as it did for the writer, so too will it for the reader. The arrested moment, the dialogue around the story, in that brief intervention, is the point at which ongoing experience is confronted just as it is about to move on. The adults and children both enter the space that exists between them, mediated by the wonder of storytelling. As picturebook makers, our job is to help to provide a story that allows them to explore and experience that nurture moment, as children come to reaffirm what they already know and to try and understand what they know not. This is where such dialogue should take place, in art and words, not on news programmes; art provides the platform for storytelling experience.

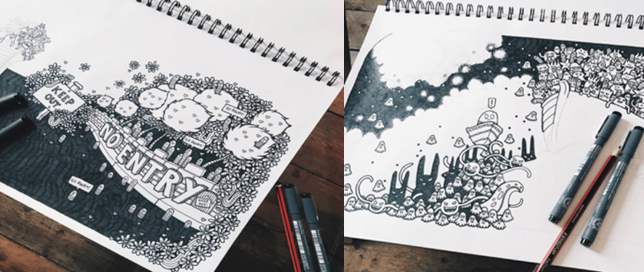

Even without these contentious issues, creating a picture book is one of those strange artistic experiences in collaboration, where two people are trying to tell a single story through a single medium. In our case, I had to write around 300 words into a story and Stephanie had to interpret the words and turn it into something a child can approach without being intimidated by the form or content; and then I react to the pictures and often rewrite the words, as the story evolves. Of course it isn’t as simple as this: as the pictures here reveal, we are constantly writing and drawing and rubbing out and scoring out and rewriting. And then new images change everything and the words change to adjust the tone, the ideas and the structure as we bounce ideas back and forward.

At one time I, as the writer, suggested we had no words at all, just images, and Stephanie, as the artist, wanted the words. It’s a constant process of passing material to and fro until we are happy we have something right. And then we canvassed the opinions of others, including the peer group we are addressing. I am happy to say that we, along with Jonathan Rooke and the University of Winchester’s Faculty of Education, Health & Social Care, the Faculty of Arts and linked primary sector schools, managed to test run the story with huge success.

It’s a necessary dialogue. The Government position in Australia is well documented; in the UK, before the Brexit vote, our Prime Minister, Theresa May said, ‘The aim [of her Government] is to make Britain a really hostile environment for illegal migration’. As writers and artists we were confronted with the need for a dialogue without the demagogue rhetoric from a largely conservative agenda of antipathy. Inevitably, when you become involved in a project like this, there has to be an element of compromise. But we found that the collaboration of ideas is the equalisation of people coming together on a common cause; there are no hierarchies, just hard work in the creative process. In some ways, then, making art is the perfect carnivalesque.

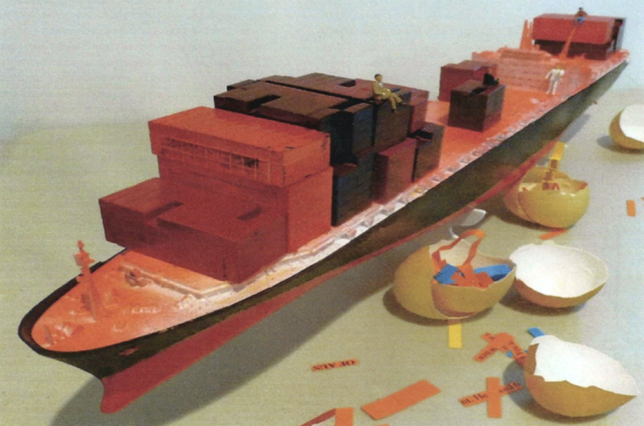

However, news starts to travel and you realise you are not alone and that indeed there is a carnival of protest taking place elsewhere and while we may be separated by borders and miles and even huge time zones further collaboration can take shape. I was soon involved in other art projects. For example, in 2016, Jen Webb (as artist) and Paul Hetherington (as poet) in Canberra, Australia, asked me to become involved in an Australian art project called The Tampa (pictured below © Jen Webb, Paul Hetherington and Andrew Melrose). I knew the story: in 2001 the Norwegian freighter MV Tampa rescued 433 refugees (predominantly Hazaras of Afghanistan) from a distressed fishing vessel in international waters. The Australian Government refused to allow them to enter Australian waters. It was a challenge I had never received before.

I began by asking myself a few questions, just trying to get an angle, and I confess I had a number of false starts. Then a nagging thought came to me. What would a ‘forced migrant’ who was escaping on rickety and creaking boats take on board with them. Essentials are easy: pants, socks, some warm clothes, maybe a change of clothes should they get wet, water to drink on the journey; it all seemed too obvious. So I thought, what would remind them of home? A photograph? A letter? A keepsake? And then out of thin air came the idea of your mama’s music box. And I thought, what if the song was a kind of dialogue.

So with a pencil and a notebook I started sketching out an idea, trying to get a story and it came in the form of a dialogue between a man and his wife:

He saw it on the TV, she read it in a magazine, life in the west, where they can be free. ‘It’s a long way across the ocean, many nights at sea, but we can make it,’ he said, ‘you and me. We'll pack your mama's music box, wrap it in a bag; you can play it when the baby cries and you’re feeling sad. Here we walk on egg shells, trying not to break; they don't want us here - it’ll be better over there.’

‘There's boat in the harbour, leaving tonight. I paid the captain, we'll be leaving by moonlight. It’s a long way across the ocean, many nights at sea, but we’ll be welcome there, so much better than here. Say goodbye to the fortune teller, send her bad news away, kiss your sister and tell her, we will send for her someday. There's a boat on the water, leaving tonight, and they don't want us here, it will be better over there.’

It is a story of hope, celebrating a temporary liberation and hoping for a better life but the music box allows for the nostalgia that comes to visit all of us who move a distance from home. After that it was a simple case of pulling in a tune and then turning it into a song, which you can read here (and hear here): https://soundcloud.com/user-659881458/your-mamas-music-box

Your Mama’s Music Box

He saw it on the TV she read it in a magazine

life in the west, where they can be free

Its a long way across the ocean - many nights at sea

but we can make it he said - you and me

Chorus

We'll pack your mama's music box and wrap it in a bag

you can play it when the baby cries

and your feeling sad

But here we walk on egg shells

trying not to break

they don't want us here – it will be better there

There's boat in the harbour, leaving tonight

I paid the captain we'll be leaving by moonlight

It’s a long way across the ocean many nights at sea

but we’ll be welcome there - so much better than here

Chorus (repeat)

Bridge

Say goodbye to the fortune teller

send her bad news away

kiss your sister and tell her

we will send for her some day

There's a boat on the water

leaving tonight

and they don't want us here - they don't want us here

© Andrew Melrose, 2016

Work is what we do, but it is art which reminds us who we are as caring, thinking people. An inside outside story of ‘forced migration’ can easily be dismissed as a soft option for the liberal minded. I take solace from Bertold Brecht who said:

With the people struggling and changing reality before our eyes, we must not [my italic] cling to ‘tried’ rules of narrative, venerable literary models, eternal aesthetic laws. We must not derive realism as such from particular existing works, but we shall use every means, old and new, tried and untried, derived from art and derived from other sources, to render reality to men in a form they can master (1977: 81).

Life is a constant carnival of haves and have nots, inside and outside ideas and dialogues are a necessary part of keeping hope of equality alive. The Boat and The Tampa and ‘Your Mama’s Music Box’ are about keeping the dialogue box open.

Pictures © Stephanie Morris, 2017

Bakhtin, M 1984 Problems of Dostoevski's Poetics [1929] ed. and trans. Caryl Emerson, introduction by Wayne C Booth, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press

Brecht, B 1977 ‘Against György Lukács’, in T Adorno, W Benjamin, E Bloch, B Brecht, G Lukács, Aesthetics and politics: the key texts of the classic debate within German Marxism, trans. R Taylor, London: Verso, 68-85