We make judgments every day about all kinds of things. Whether wrestling with student assignments or finessing a paper for publication, the same critical principles and rational processes apply, so making judgments about paring back personal clutter should be comparatively easy—or is it? As one horsewoman found out, an exercise in defragging the horse stuff was about as conflicted and complex as it gets.

My life is complex, although not especially complicated. If I could draw my life I fancy it would look like one of those ornamental wicker balls, with all the strands interwoven and feeding into and across each other. This structure is both strong and flexible. Each strand represents an aspect of my life: work, learning to draw, crafting words, teaching and thinking, home, housework, family, friendships and my animals—especially horses—all plaited together and wrapped around my inner core.

I mention horses because they are profoundly important to me. I can’t imagine a life without them. Living with horses has given me more than strong calf muscles and a straight back: horses have shaped the way I think. They have taught me to be patient and to own my mistakes, to let go, and to think things through. I think my deepest thoughts and have my best ideas when I am riding; but most importantly, because of horses I have learnt to trust my own judgment.

Interestingly, one definition of ‘judgment’ is ‘common sense’ or ‘horse sense’, which resonates reassuringly with my equestrian narrative. Whatever the origin of the word, however, acts of judgment often have weighty consequences: a paper rejected for publication, a student failed, a friend found wanting, a novel derided. For the most part, making judgments entails considerable mental effort. Mysterious forces come in to play. Arriving at any judgment may be contingent not just on facts, but also on emotions, pragmatism, experience, aesthetics, sentiment, necessity, expediency, practicality and, most inexplicably, following your intuition.

Nothing illustrates this better than when I decide to clear out of my horse gear. Horse owners are hoarders. Much of what we buy is expensive or unique, which makes it difficult to throw away. Even if it is broken, outgrown, damaged beyond repair or useless because only one of a pair can be found, we tend to hang on to everything ‘just in case’. Every few years, however, when I have scrabbled once too often through piles of old buckles, toothless mane combs and unidentifiable pieces of leather looking for a half-remembered set of reins or an extra-long girth, the time has come to purge, to make those difficult judgments about what to keep and what to discard—to defrag the horse stuff.

A heavily fragmented drive makes reading and writing data slower; thus the desire to process more efficiently encourages defragmentation.

‘Defrag’ is a lovely word and I like it very much; it has a crisp, determined, decisive sound – two hard consonants with a spitty exhalation in the middle. Despite it belonging to the world of technology, ‘defrag’ is the word for me. This week I am tidying the hard drive, purging my life of extraneous items and reorganising the survivors. Having spent 25 years working as a librarian I know the importance of storing like things together, and the need to free up space through a rigorous regime of weeding. My horse stuff is scattered all over the house, in outside cupboards, in my garden shed, alongside the walls of the house and in the boot of my car. With so many locations it is no wonder I can’t find things when I need them. Too much of it is rubbish. The horse stuff is out of control; it’s time to rein it in.

Operating system manufacturers often recommend periodic defragmentation in order to keep hard drive access as fast as possible.

My defragging crusade has been brought on by the annual mystery of the flyveils. At the end of every summer I wash the flyveils and put them into storage and, at the beginning of the next summer, when I need them again, I can’t remember where I put them. You wouldn’t think there would be a huge difference between books and bridles; you would think that, for a trained librarian, filing flyveils would be a relatively simple thing to do; but somehow, it isn’t. This summer was no different. Did I do the logical thing last autumn, and file all the flyveils together? Not at all—I found the wretched things all over the place. Several were stuffed randomly into gaps between other pieces of stored horse gear, I found one under the front seat of the car and another squashed into my bridle bag, and yet another one was returned by a friend who found it in the folds of her summer rug. She rarely uses a summer rug but once a year she shakes it out and puts it in her car just in case. Who knows how the flyveil ended up cocooned in her rug?

Eventually I turned up 11 flyveils—both horse and human—which suggests that the last time I went looking for flyveils their fragmentation meant retrieval was too slow and I must have given up and bought new ones instead. Perhaps if I got rid of the non-essential items of horse equipment and reorganised the rest, the mystery of the flyveils might be put to rest, my wallet would get a break and my hair might stop going white.

11 Flyveils

Fragmentation occurs when the operating system cannot or will not allocate enough contiguous space to store a complete file as a unit, but instead puts parts of it in gaps between other files (usually, those gaps exist because they used formerly to hold a file that the operating system has subsequently deleted).

Part of the problem with storing my horse gear is that I don’t have a garage, only a carport that is not secure. I do have a small garden shed I use to store hay and a collection of buckets (some with handles, some with lids, and some with neither), six spare saddle blankets, a couple of western pads and two winter and three summer horse rugs that don’t actually fit my current horse. The frame at the bottom of the shed doorway went rusty and disintegrated years ago, so the sliding door no longer slides but is jammed wide open, meaning anybody can walk in. I don’t really care if thieves steal the horse rugs or even the saddle blankets but I would be very annoyed if the hay went missing. I keep most of my horse gear in the house, packed in plastic boxes I keep in a wardrobe in the spare room and crammed into some low shelves in the utility room that leads out into the carport. There is also a tall cupboard built into a recess in the carport wall. It houses paint tins and out-of-date garden sprays, together with a collection of balding horse brushes, a tangle of old nosebands and bridle parts that might come in handy, and a couple of dust-bunnied lunging whips that have not seen the light of day since my son used them to practice whip-cracking out on the driveway 15 years ago. There is enough space in the bottom of this cupboard to store a pair of gumboots, but it hasn’t rained enough in the past few years to warrant me wearing them. I would say from the cobwebs across the tops that the boots are now the home of several generations of spiders.

Jammed in next to the boots are two big zip-up plastic bags. Originally containing newly acquired quilts and bedspreads, the bags now hold a weird collection of crocheted sweat rugs, thermal leg wraps, more cotton summer rugs and a very nice yellow collar-check woollen dress rug that once looked especially spiffy on my palomino quarter horse Rikki, in the days when I used to go to horse shows. I don’t go to shows anymore, but I still love that rug. There is also a set of faded plastic dressage cones in this cupboard, leftovers from the days when I taught people to ride. The letters have rubbed off, making them less than useful, and they occupy the floor amongst drifts of dust that bind together clumps of mud, brittle leaves and flakes of chaff. Having once disturbed a hissing blue-tongue lizard when I moved one of the gumboots, I tend to leave the contents of this cupboard alone.

Two 44 gallon drums, one small metal barrel (ex-Government Mint, originally used for storing coins), a plastic rubbish bin and various sized buckets for storing horse feed line one wall of the carport. I wish I could find another space for the bins. I have been contemplating this problem for the past 25 years without coming up with a solution. Meanwhile I find that I have dumped two carrot sticks, a polocrosse stick, a polocrosse ball, the dog’s throwing stick, several empty juice bottles and a cracked plastic colander in the corner of the garage. You can see how things have become fragmented and how, as a person whose linen cupboard is neatly arranged by subject (towels on one shelf, sheets on another, and who pegs underpants in groups (‘his’ on one strand, ‘hers’ on another) and the socks in pairs on the clothesline, I might be driven mad by the barely organised chaos of the horse gear.

Once upon a time, when I used to run with the competitive crowd and had regular, serious dressage, jumping and cross country lessons, I couldn’t get enough horse stuff and I bought a terrific amount of gear. I was always on the lookout for a better bit, a plumper saddle blanket or a more aesthetically appealing set of leather jumping boots. I love leather. To me, the aroma of new leather beats French perfume hands down; and dull brass fittings attached to polished leather strapping are just too beautiful for words. Leather is thirsty, high-maintenance material and it needs regular cleaning and polishing to keep it supple and strong. I don’t mind cleaning leather. I don’t mind getting stuck in because the end result is always worth the effort. What I do mind is trying to remember where I put the saddle soap.

Now I find I don’t use nearly as many gadgets and fancy pieces of equipment as I did in those early days. Back then I thought a new piece of equipment would solve every problem: poorly fitting saddle? Try the new Gel pad. Horse opening his mouth? Shut it with a drop noseband, a grackle, a Hanoverian, or one with the latest crank fastening device. Lordy you could wind those things tight. Horse throwing his head up? Buy a martingale, or a complicated device harness called a de gogue, or a pair of draw reins. There are dozens of books and magazine articles devoted to horse gear. I studied them all and hit the horse shops looking for whatever piece of equipment I thought, at the time, I really needed.

Then there was the pressure of competitions. There was no room for individual fashion statements or quirky equipment in the ultra-conservative, tradition-soaked worlds of equestrian competition. While I did push the boundaries a little by competing in those very English disciplines on Rikki, who looked as if he should have been chasing cattle, I made sure that we both looked the part. I owned a hacking jacket, a couple of shirts with ratcatcher collars, white jodhpurs and black gloves. The requisite black leather top boots were a problem because, at around five hundred dollars a pair, they were the one item of gear that I couldn’t afford. For years I wore synthetic top boots – okay, except they squeaked loudly when they rubbed against the saddle and, being made of non-breathable material, they made my feet stink. I overcame this lack by agreeing to become the Chief Instructor of the local pony club, the inducement being two pairs of second hand leather top boots. It was something of a compromise because while one pair of boots was too small and a truly hideous shade of brown, the other pair was too big by at least a size and a half. I stuffed them with newspaper and wore them all the same, trying not to trip over the extra-long toes. Because they were painfully tight around my calves I couldn’t walk very well in either pair. Within a few minutes of pulling them on I had to sit down because they made my legs throb. Needless to say, the boots have been retired for a number of years.

I tried them on the other day, just for fun, but I couldn’t close the zips so it really is time for them to go; although I might just hang on to the black pair because while they are both too big and too small, they are the right colour and they are made of leather. Who am I kidding? If I ever experience a rush of blood and decide to compete again, perhaps in something age appropriate like the Masters Games, these black boots would be so far out of fashion they would look even more ridiculous than when I first wore them.

The black leather top boots

Today, proper safety helmets are compulsory in nearly all equestrian disciplines. We used to wear velvet covered ‘hard’ hats and tucked the chinstraps up under the crown. We might just as well have worn paper bags on our heads for all the protection they afforded. We all owned a separate set of show gear for best—a best whip, a best bridle and a best white saddle cloth. When we were jumping, the horses wore leather leg protectors. They looked smart but were frustratingly fiddly to put on. They had several sets of buckles with short straps that were difficult to do up, especially when the horse was excited and wouldn’t stand still. Those lovely leather boots had to be cleaned and oiled after every use otherwise they ended up cured to the consistency of old cardboard, and no amount of oiling would soften them again. The alternative to the leather brushing boots was to wrap each leg in a white bandage which, for safety reasons, had to be sewn. Imagine trying to do that with a horse that was stamping its feet with impatience. It was a relief when all this paraphernalia was eventually replaced by simple neoprene boots with Velcro fasteners. They are quick and easy to put on and a swish through a bucket of water has them clean and dry at the end of the day.

If you believed the British magazines (and most of us did), competitors were also required to sew the braids into their horse’s manes and tails. We didn’t follow this regime in Australia, at least not at the level of competition in which I participated; instead we used special rubber bands to hold the plaits in place. They were tiny things, extremely difficult to stretch, tricky to apply and impossible to remove. You needed sharp scissors, a steady hand and endless patience to unbraid manes and tails at the end of the day. If you tried to hurry the job the results would be disastrous as large clumps of hair were snipped out with the rubber bands and you finished up with your horse looking like a punk rocker. It takes about 12 months for that sort of damage to grow out. It’s been years since I plaited a horse’s mane but I still find little white rubber bands wherever I keep my horse gear. They flutter down from shelves and melt messily to the bottoms of boxes and it’s this kind of useless untidiness that periodically drives me to defrag the horse stuff.

This won’t be the first time I have defragged my horse stuff. I did it in a very big way when I took up Parelli Natural Horsemanship. PNH was a culture that shunned nearly all the ideas about keeping and training horses that were held by traditional horse people, who solved issues with problem horse with equipment instead of training; or so Pat Parelli told us. He called it the ‘bigger bit’ syndrome and encouraged his followers to purge their tack rooms of all equipment that was overtly mechanical, relied on force or was blatantly cruel. I had quite a few dubious items, although nothing like the ‘shank bits, long-necked spurs and barbed wire bits’ described in the PNH literature. I got rid of the nosebands that were designed to keep my horse’s mouth shut—far better to fix my horrible hands than force my horse to put up with them. I discarded my not inconsiderable collection of bits—an assortment of fat egg butts, loose ring, Mullen mouth, roller and French snaffles. They were all fairly innocuous by any standards but Parelli favoured thinner, sweet iron bits with copper inlays. Apparently horses preferred them, and who were we to argue with such wisdom?

Apparently I didn't throw them all out

Parelli also favoured hand-tied rope halters. He said they had more feel and, unlike flat halters, discouraged horses from leaning on them and ignoring their handlers, so out went the flat halters. Gone too, were the running martingales, and the de gogue of course, the lunging cavessons, draw reins and dropped nosebands. We were told that if we couldn’t get our horses engaged, light and travelling willingly and kindly without these sorts of devices, then we should stop torturing them and instead address our own lack of horsemanship skills. It was humbling and dramatic enough for me to review all the other unsuccessful contraptions in my arsenal of equipment that, if I were honest, never really worked for me or my horse. We were supposed to take this all this ‘bad’ equipment to the nearest rubbish tip and dump it, but I needed the money to pay for yet another Parelli course, so I put mine in a secondhand gear sale, with apologies to the horses whose owners bought it.

A defragmentation program must move files around within the free space available in order to undo fragmentation. The presence of immovable system files (or of files that the defragmenter will not move in order to simplify its task), especially a swap file, can impede defragmentation.

It is probably 20 years since I did the big Parelli-inspired defrag but in the meantime I seem to have accumulated even more horse gear; more than I will ever need. Fashions change; the old equipment doesn’t fit the new horse; I’m following a different discipline; things wear out—but not enough to be thrown out.

There are all sorts of reasons to keep horse stuff. I have, for example, quite a bit of horse-related human clothing that I will never wear again and indeed, there are some things that I own that I have never worn at all. In the big cupboard at the top of my wardrobe is a beautiful handknitted sweater. It is black with a big gold PNH horse head logo splashed across the front and PNH worked in gold wool around the hem. A friend made it for me at a time when we were both struggling to make sense of the Parelli Natural Horsemanship program. I don’t wear the sweater anymore; it was always a bit tight and today it is even tighter. But every so often I pull it out of the cupboard to remind myself of all the clinics and the laughter, the impossible tasks we were given, the fantastic meals we shared, the screaming highs and the gut wrenching lows, and that terrible time when Rikki ran away with me and I thought I was going to die. There is also a blue felted western-style riding jacket, with a short waist and fancy braiding on the cuffs and lapels. I bought it from a mail order catalogue on a whim, because it was cheap and I fancied the notion of myself jogging around in a western pleasure class at the Canberra Show. I never did compete in Western Pleasure and I never wore the jacket, except once, on a visit to my mother who regarded it with raised eyebrows. It has been folded up in the top of my wardrobe for years and I doubt that the creases will ever come out.

The Parelli Sweater

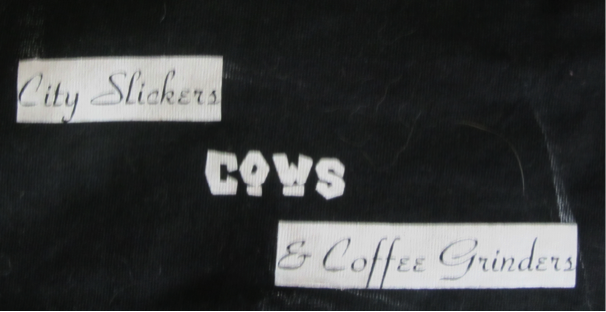

There is also a collection of tee shirts from my Parelli days. They commemorate the many Parelli camps I attended at Exeter farm near Braidwood in New South Wales. They all have inexplicable phrases, like City Slicker Cows & Coffee Grinders, printed across the front and they are in sizes that only size zero super-models could wear. Sizing was always a problem with Parelli clothing, probably because the organisation was staffed by the thin, the blonde and the beautiful who seemed to have difficulty acknowledging that there are women in the world who are bigger than a size ten. The tee shirts were given away at the camps as a sort of reward for surviving, although I rather think the fees we paid to attend the camps more than covered the cost of a ‘free’ tee shirt. The distribution of these tee shirts took place in the shearing shed at meals times. To the accompaniment of catcalls and frenzied foot stomping, the staff would throw shirts randomly into the crowd, and anyone lucky enough to catch a rare size L (actual size M), was disinclined to swap. My tiny tee shirts are stored in a plastic bag in a drawer in the spare room, together with a couple of ‘free’ bandanas stamped with the Exeter Farm cattle brand—but who wears bandanas? They are in the spare room because I have run out of space in my wardrobe. They have been there for some time and they have so many memories attached to them that I am beginning to think that they might be immovable.

One of those "free" tee shirts

The reorganisation involved in defragmentation has nothing to do with the logical location of the file.

Of course, the more I keep, the less storage space is available and unless I buy a bigger house, defragging is the only option. I try to keep like things together but what starts as a system—boots and leg coverings in one box, bits and bridles in another – soon breaks down. I thought if I stored everything in a series of plastic wheeled containers with lids, it would stay neat and tidy and accessible forever. Fat chance. I bought deep boxes because they hold a goodly amount of stuff. This proved to be both a good thing and a bad thing: instead of throwing things away, I just squashed them in and, when the box was full, using the out of sight, out of mind principle, I wrestled the lid on and wheeled the box into the bottom of a cupboard, and then forgot about it. As each box became full the classification system fell apart, so I began to stuff things in wherever there was space.

Boxes full of assorted junk

When I started, there was so much space, and I kept all sorts of ridiculous things. Why have I hung onto lengths of decaying mildewed leather—origin unknown; or handfuls of buckles and clips, pieces of girth rigging and countless stiff, old fashioned, narrow leather reins? There is a rather lovely old-style double bridle someone gave me years ago. I don’t really know what to do with this strange tangle of leather and metal, but I know I am not ready to give it up—it is too beautiful. Maybe one day I will give it a loving polish and hang it on a wall like a work of art. I also have a very nice one-eared western bridle, a gift from a friend, although I never had a horse that could tolerate wearing it.

The one-ear western bridle

The double bridle

The collection of broken whips can go, except for the leather covered one my father gave me when I was nine years old. The leather flap has long gone, but the whip reminds me of my dad and my first horse. I was going to throw out the gel pads, those once fashionable but now outdated back protectors for horses, but happily, in the summer of 2009 when the temperatures stayed in the high 30s for days on end, I discovered a new use for them. I put them in the freezer, and when they were cold and hard I placed an old towel over them and put them on the floor for the dog to lie on. I also have odd bits of Velcro, a rusted hole punch, and an awl for hand stitching leather that seemed like a good idea, except it was impossible to use. It is time to defrag the horse stuff but there is one thing I won’t throw away—an ancient metal curry comb that came with my first pony. It looks like a medieval torture device but just touching it brings back the sound and the sensation of dragging it through Chocolate’s shaggy winter coat. It is old and battered and it may even be an antique but I plan to keep it just as soon as I can find it.

Defragmentation (or defragging) refers to the process of physically reorganising files on a computer hard drive in order to store files as contiguously as possible.

To help me defrag I have made a list of essential horsey things, the items that I really need, and these include:

- One treeless saddle (although I’m not entirely happy with it and may soon have two saddles again as I am trialling a different style of saddle, and now that my tax return has arrived I am seriously consider buying it. I wonder if I have a girth that will fit it. Must be one in a box somewhere).

- One nonslip saddle pad (although I think it is starting to rub my horse – who knows why—and I may have to replace it with something else).

- One bareback pad—good for improving my riding but just as complicated as putting a saddle on the horse. Still, one day, perhaps next summer, I’ll do a bit of bareback riding again.

- One leather bridle with an American-made Myler bit attached. The Myler replaced the Parelli sweet iron. Apparently it is kinder for the horse so I thought it was worth a try. Seems to be working. I should put the old sweet iron bit in the box with the other bits because you never know I might need it one day. Trouble is there’s no room in that box. Perhaps if I leave it in my bridle bag for now.

- A bitless bridle (bought as an experiment and, I would say, so successful that both my horse and I prefer it to the bridle. Sadly it is made of plaited nylon, not leather; although I have seen a leather one for sale so I might just get it).

- One rope halter and 12-foot lead (well, two really. The other is a spare set I keep at the paddock).

- A grooming bag with a collection of brushes, combs, hoof picks, sweat scrapers and the like. Actually, I could throw most of it out because right now Myst, my current horse, loves nothing better than a firm brushing with an old human hair brush bought for $2.50 from Priceline.

- One big blue rubber trug-style feed bin (and another black one for when we go away and a smaller one for water, plus a spare just in case).

- An old 2-litre juice bottle used for dog water, wetting the feed and washing off the horse after riding.

- One helmet.

- A pair of gloves (somewhere, maybe in the outside pocket of the bridle bag?).

- One pair of riding boots, short, synthetic. I also have a pair of zip-fronted leather Ariats—smart if a tad tight, but they cost me a fortune and I can’t bear to throw them away.

- Four flyveils (two for the horse and two for me just in case we misplace one, plus, of course, all the spares that recently turned up).

- One acupressure photon torch for treating injuries, staving off colic and general health maintenance for the horses, dogs, cats and humans in the family.

- Hoof stand, file, knife, and gloves for trimming Myst’s feet between the farrier’s visits. (Yes, I know I should call him a trimmer but old ways die hard.)

- A set of horse boots for Myst, because she is barefoot and sometimes her feet are tender on stony ground.

- A box of basic first aid stuff including ointments and sprays that keep going out of date because with the Photon torch, Epsom salts-soaked bandages and Manuka honey, I rarely need them. NB: I recently added a swathe of very expensive wound padding bought from the vet when Myst cut her hock, before I discovered that disposable nappies are cheaper and just as good.

Of course I have a couple of halters and lead ropes that I use when travelling the horses in the float. And yes, I have a horse float which is probably the only item of horse equipment that has any resale value. I should get rid of the 22-foot and the 44-foot ropes left over from my Parelli days when I thought I would die if I didn’t have such things, but they have their uses.

My horse life is simpler now and I don’t seem to need as much gear as I used to. This means that apart from the items on my list, everything else can go. I know that when I finally get around to defragging the horse stuff it will be better to do it on a day when I’m feeling irritable. I’m much more inclined to be ruthless when I’m in a cranky mood and that means I won’t prevaricate and change my mind—which is how I got into this fragmented mess in the first place.

Like anyone I constantly pass judgment and it’s not just about the horse stuff. As an academic I judge the work of others—my students, my peers and my colleagues. As a creative practitioner I judge my own work, always with that small underlying voice of self-doubt playing below the surface. Is it good enough? Should I keep it, send it off, or just throw it away and start again? It takes more courage to throw something away than it does to bury it in the bottom of a drawer. Whether we keep everything or start again, stuff accumulates, then it spreads, it becomes messy, the carefully constructed system collapses, we can’t find anything and before you know it, we have to defrag.

I should be able to do it this time, but the real test will come when I go shopping – not in the saddle shop although here are plenty of temptations there, but in one of those cheap two dollar shops. You see, they always have big stacks of wheeled plastic boxes with snap on lids and coloured handles for sale and these make ideal storage containers—and, despite my bouts of defragging, I have quite a few things that need storing—bits of horse gear, draft poems, old course notes, receipts, the dog’s winter jacket.

PS: Look what I found—my old metal curry comb. It was in a small, dust-covered plastic box on a shelf in the carport cupboard together with a brush with a broken handle, a clump of perished rubber bands and an assortment of broken snap hooks and rusty buckles.