The mushroom cloud dispersed rapidly. For a few seconds it took the intriguing shape of an aboriginal face silhouetted over Australia, then it eddied 1500ft high, and was blown away to the north-east... (Douglas Wilkie, the Courier-Mail, Brisbane, October 16, 1953)

I

Es atmet mich, it breathes me,

this cremated field,

whose pulmonary veins were fused

by atomic blasts.

It is breathing slowly

like a heart, or an animal dying

and in the periodicity of its own blood

is become sternklang,

the language of stars.

In the 1950s, Robert Menzies

surrendered this desert to men who look down

from flag-draped podiums

and parliamentary stairs.

They built bombing ranges that

from outer space resemble

occult sigils.

Es atmet uns, it is not in the nature of demons

to refuse such invitations.

Low on the horizon

a greasy cloud makes whispering noises

as it advances

erasing the mulgas.

Sun glints from its surface

like something solid.

And its interior is the muscle

of a snake, coiling recoiling—

it dislocates its jaw

and spews blackened birds

into the desert,

Wedgetailed eagles

with their eyes burned out.

Soldiers club them from air

with axe handles—

some of them are crying.

Do you remember?

These rivers, these mallee and paper daisies

We took it all away.

II

A summer of aeroplanes,

of air excited

by radios: public, private, and military.

Ten year old Yami Lester played on Emu Field,

that day when all birds vanished,

when nothing in that grassland breathed.

And turning,

by instinct, stopping

he pressed knuckles into his eyes

a split second before the flash and double boom

roared toward him like a crashing road-train.

And traveling in that sound,

a blue-white diamond,

a second sun

passing through the bones of his hands,

left x-ray impressions

of blood and skin,

the intricate network of nerves,

and his eyes

burned.

It was black when the pressure wave hit

a feeling of being underwater,

and then the air sucked back,

billowing out his body like sheets on a line.

He didn’t see the rain

that smelled of chemicals and fell

in dense heavy drops

but he heard its tattoo

and distantly, from the direction of houses,

his mother screaming.

III

When they came to Juldil Kapi,

called Juldi, called Ooldea Soak,

the United Aborigines Mission,

in Jeeps and covered trucks

they looked like moon men.

Soldiers everywhere,

the older ladies recalled.

Guns. We all cry, cry, cryin’.

Time enough to pack a dilly bag

of clothes, a framed photograph,

a child’s favorite toy,

before the trucks rolled out,

leaving mission buildings to heat

and swallowing dunes.

And she, between soldiers,

on those hard troopie seats,

secretly fingers a stone

held deep in the pockets of her skirt—

nulu stone, she thinks, last fragment

of the meteor.

Its dust colors her skin.

A hundred kilometers to the south

departing helicopters drop leafets

written in English

warning Aboriginal people

to not walk north.

But here on the savannah,

groups of figures separate in spinifex.

And later, when sky pressed toward them

like a wall, they laid their bodies

over their children

and rose again coated in tar.

Soldiers found them sleeping

in the Marcoo bomb crater.

They gave them showers

and scrubbed their fingernails.

But in the months that followed

their women gave birth

to dead babies, to babies

without lungs, babies without eyes,

and their men speared kangaroos

they couldn’t cook

because they were yellow inside.

IV

A marquee stood on Emu Field

among fruit trees, with chairs and tables

for politicians and members of the press.

They served lemonade

and plates of sandwiches.

Songbirds

flitted in the eaves of a grandstand,

purpose-built for compelling views

of the mushroom cloud.

And after the last bus,

when the marquee was packed away

and only uniformed men flashed binoculars

on the grandstand,

they ordered their soldiers

to crawl

on all fours through atomic fields.

Their bodies drag the dust.

On a clear day, you could see their backs lifting

though layers of mist

like elephants bathing in the Ganges.

And those who flew Lincolns into fallout

came back without throats—

coincidence, the English courts explained,

we all smoked back then . . .

But I want to know what happened to my grandfather—

dead before fifty from multiple cancers.

They gave peerages to nuclear scientists

and to soldiers, melanomas

and the chance to buy an unofficial medallion

for thirty dollars.

And I want to know what happened to my uncle—

dead before sixty from heart attack and stroke.

Cells transform into other cells,

like the songbirds of Emu field

whose calls were the silver

of shaken metal fragments.

I want to know if I’m going to live—

You’re young, the surgeon said, for this kind of cancer.

But he couldn’t tell me

how people become dust,

how sand becomes glass,

or how Menzies could send soldiers into atomic mist,

and still hold the word God in his mouth.

V

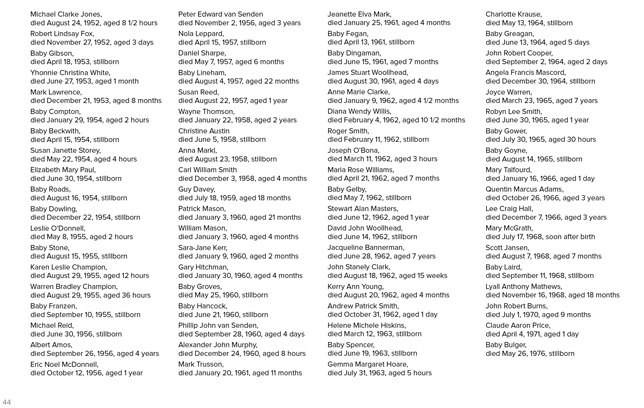

At Woomera,

seventy-five identical graves

remember babies lost to the predation

of atomic clouds.

Their epitaphs are brief—

Michael Clarke Jones

died 24 August 1952,

aged eight and a half hours.

No one has been here for a long time.

Weeds struggle.

A military vehicle passes,

heading east toward the rocket range.

In the west, Woomera township

is a grid of air force housing.

Land Cruisers fill neat driveways,

lawns are trimmed,

blinds closed.

And no one ever steps out for milk,

no one walks a dog.

I photograph each headstone,

stooping sometimes to straighten a plastic posy,

a tilted ceramic bear.

Wind presses a faded greeting card

to the metal fence.

A matchbox car beside a small boy’s grave

is blue.

There are nineteen stones without toys or flowers,

for stillborns named only “baby”—

Baby Spencer,

Baby Dowling,

Baby Stone.

Don’t look at me

Baby Gower

Baby Roads

from a soldier’s gunny bag

with your eyes too white, too open

like the eyes of poisoned fish

tumbling

in the Pilbara’s poisoned surf

Was it night when they came?

those soldiers who emptied the graves?

A secret harvest

of twenty-two thousand children

whose bones were crushed

for Strontium-90 tests in the UK.

Their parents were never told.

The ground here is hard.

Centuries of heat-fueled wind

have baked clay to shale.

To open a grave you’d need

sledgehammers,

pickaxes,

crowbars.

It would not be gentle.

I see them starlit,

shadow-striped by the wire fence,

they draw a baby boy from earth—

pale as a frog

mud-marked

and he wears my grandson’s face.

I don’t want to tell him

our bombs unleashed a serpent

older than names,

that hung over the neonatal ward,

above the cots of Woomera,

and the gaze of its lidless eye

returned them all to namelessness.

My grandson,

I don’t know what world will be left to you