When Sydney’s Daily Telegraph marked the death of cricketer Phillip Hughes in 2014 with a full black page, it added to the catalogue of works relating to Laurence Sterne’s black page in The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman that marks the death of Parson Yorick (p.73 of Vol. I of the original edition). The black page may be a meditation on absence but it also evokes—through that absence—the world of light in which a character played his or her part. With reference to The Black Page catalogue published by the Laurence Sterne Trust in 2010, which featured commissioned works by 73 writers and other artists, the author here describes his own contribution and explores how other artists’ multimedia works have approached the challenge of depicting light where apparently there is none.

Keywords: Laurence Sterne—Tristram Shandy—black page—textual intervention

The Black Page exhibition at Shandy Hall in 2009 celebrated the 250th anniversary of the publication of volumes I and II of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman by Laurence Sterne. In volume I, page 73 is a black page that marks the death of Parson Yorick. The Laurence Sterne Trust commissioned 73 writers and artists to make their own interpretations of the black page; each was given an exact template of the original. ‘Use your blackest black’ was the enigmatic instruction that came with it.

The plan was to exhibit the 73 works, anonymously, and to auction them, with the bidding starting at £73. This was an intriguing part of the project, because there were world famous artists involved—Rachel Whiteread, winner of the Turner Prize; Cornelia Parker; Tom Phillips—but none of the visitors or online bidders would know who had done what, if indeed there was to be any difference. What would be produced—73 identical black pages? Would it turn out to be an exercise in the banal?

We only have to investigate Sterne’s own black page to be reassured. The typical reproduction nowadays may be a consistent black, but as the Black Page catalogue explains:

Achieving a solid black page in Sterne’s day was not a simple matter. Ink was a mixture of refined linseed oil and ground soot. Also inking rollers, which can give an even coverage, were yet to be invented. [...] the Black Page [was] printed from a wood or metal block, copper or perhaps lead, we can not know which.

The resultant inconsistency of coverage shows especially in splashed ink on some copies of the early editions; binding before the ink was fully dry can result in a ghost image on the facing page. (Laurence Sterne Trust 2009)

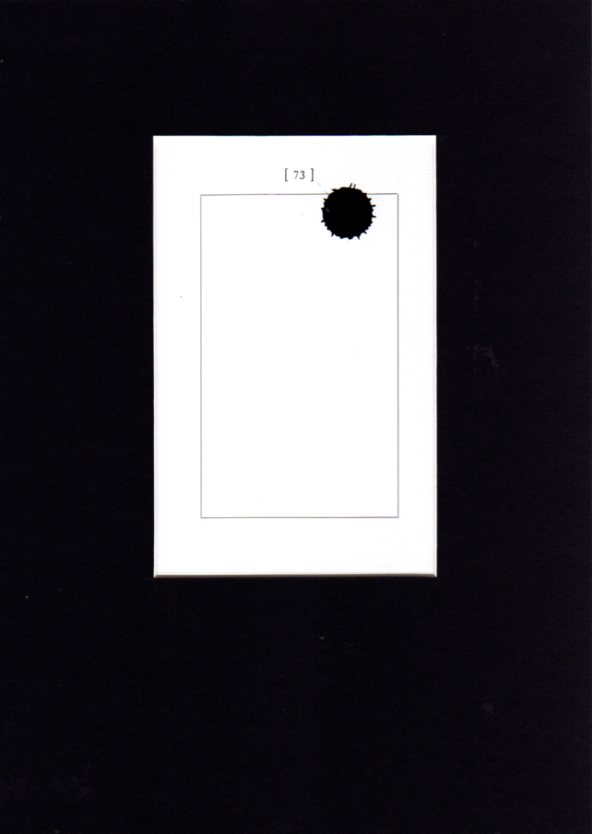

[Figure 1]

Beyond this basic issue of variability, the project brief (to use your blackest black) carried something inherently personal—and metaphorical.

Yorick of course is also a jester. Cartoonist Martin Rowson had visited this territory before, in his graphic novel version of Tristram Shandy, turning the ‘Alas poor Yorick’ moment into high farce: ‘Splat!’, ‘Kerpow!’, ‘Hell’s teeth! Why’s it so dark in here?’ Such are the captions to the moment at which the black page makes its intervention, and they continue:

It’s another stylistic device! Ouch! Y’know, subverting the reader’s metrical harmony with the conventional geography of written narrative! Ow! My toe!! (Rowson 2010 [1996]: n.pag.)

When faced with their templates, some of the commissioned Black Page artists were immediately at play, similarly mischievous.

[Insert Figure 2: BP#51, Scott Myles]

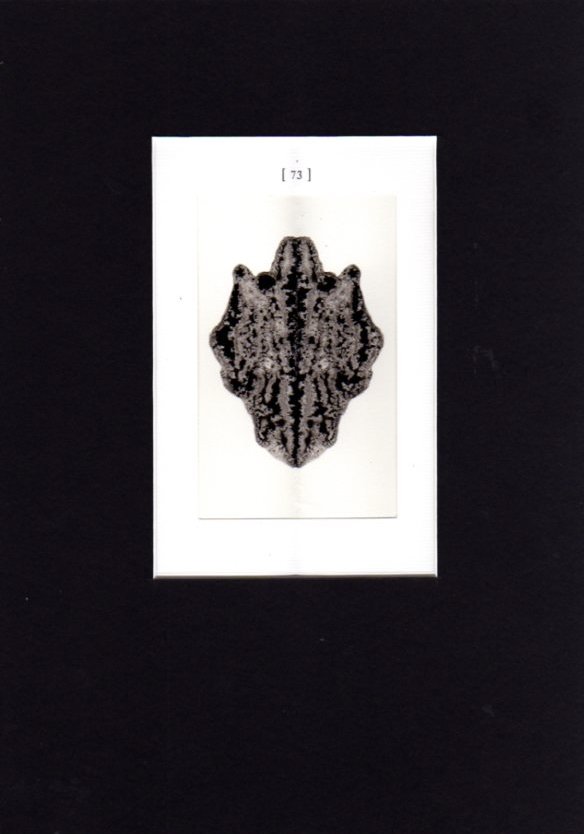

‘Splat!’, that seems to say—or is it a full stop; a termination, magnified; a ‘nothing’ made palpable? It echoes, perhaps, those splashes of ink that characterised the original, all to do with chance. The commissioned artists had to write some description of the work they produced (even if only the customary list of materials used), and in this case, artist Scott Myles wrote: ‘Similar to a Rorschach test, the enlarged inkblot gives space for free association.’ By uncanny coincidence, Cornelia Parker produced an actual Rorschach blot, of the most elegant variety. Hers is made of jet, ground into a powder to make ink; jet of course intimately associated with mourning.

[Figure 3: BP#46: Cornelia Parker]

There were other full stops. Those in Carolyn Thompson’s page were all cut from a single edition of Tristram Shandy.

[Figure 4: BP#37: Carolyn Thompson]

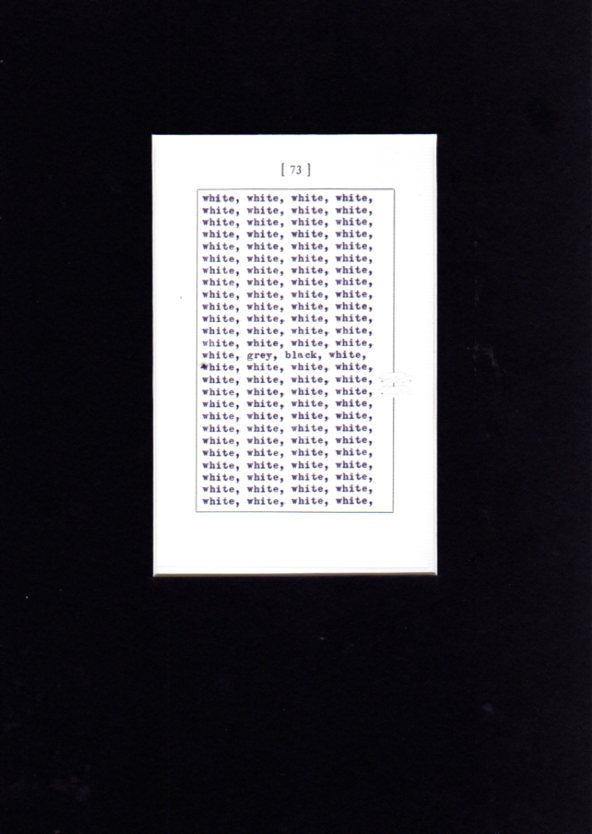

Several other obliterations involved text—sometimes text as obliteration—including contributions by Patrick Marber, Lemony Snicket (who uses ‘STET’ as the final word, the only one not crossed out), Richard Askwith, Craig Dworkin and Nigel Hutchinson. Some contributors played on the idea of writing, with ink, being by very definition a blackening—even when the dominant word is ‘white’, as in the page by Will Self.

[Figure 5: BP#6: Will Self]

Another novelist, Graham Swift, drifts into poetry: ‘Of poor Yorick think / and blacken this poor Page / with mental ink’. Hilary Mantel’s chosen excerpt from her novel, Beyond Black, also suggests poetry through the way the words make use of the space.

[Figure 6: BP#10: Hilary Mantel]

It therefore seems inevitable that poets themselves should make their contributions as poems. Jo Shapcott’s ‘Black Page’ later appeared in her collection, Of Mutability (2010), though without it’s final word, ‘Alas’.

The page opens

its dark portrait

of a rectangular mouth

and says believe

in alas. Believe

in mourning and

a proper afterlife

which you will come

to understand once

you strip off, fall in

and swim in ink.

Alas.

Thomas Lynch, poet and—famously—an undertaker, contributed a poem that would later appear in Walking Papers (2011), ‘Corpses do not fret their coffin boards’, in reference to Wordsworth’s ‘Nuns fret not at their convent’s narrow rooms’ (1975: 199). In the Oleander Review, Lynch writes of Wordsworth: ‘he’s talking about the power of poetic form. I suppose he was talking about how having to fit things into this little form forces you to make choices that you wouldn’t otherwise’ (2008: 53). In Lynch’s black page, the idea of confined space is emphasised by the title surrounding the body of the poem, making a poem as coffin. Like Sterne himself, Lynch resorts to visual elaboration.

Many of the artists do exactly as they were told—creating darkness, even if sometimes with Yorick-like light-heartedness. Particularly interesting, however, is the move evident in a number of contributions to explore, in Hilary Mantel’s phrase, ‘the place Beyond Black’. Jerome Rothenberg, for instance, uses black nail polish to create a reflected sheen (and other artists use black satin, silk, and shiny black card to similar effect), and a meat skewer to do the writing—a translation of Paul Celan’s ‘Death Fugue’ (1948). As a result, instead of the writing making a black mark, it actually creates light within the dark.

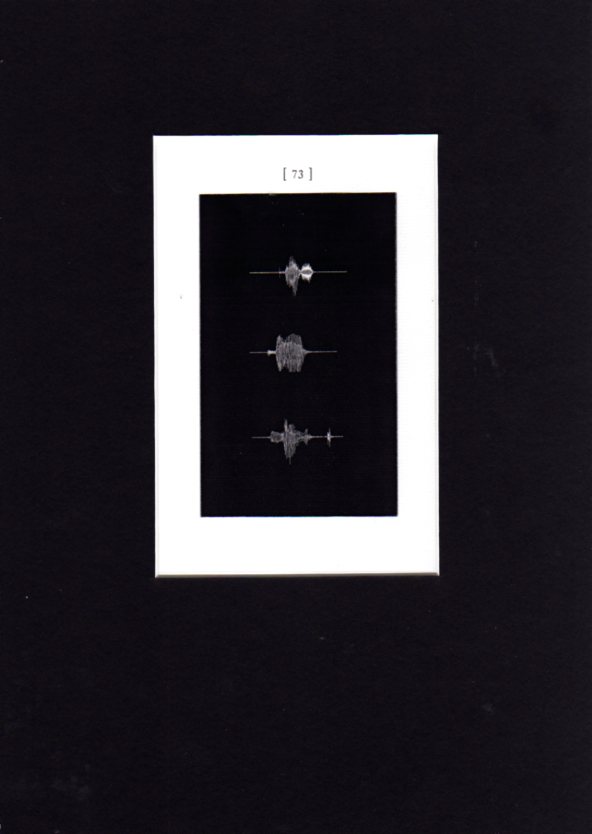

This complication is further enriched by virtue of the variety of artists involved in the project: writers, visual artists, and also composers (including Harrison Birtwhistle and Michael Nyman). The example below [Figure 7] is by Craig Vear. The three marks punctuating the page are the waveforms of the sounds of the words ‘Alas, poor Yorick’, as spoken by the composer; light making its presence felt within the darkness, as sound does in silence.

[Figure 7: BP#16, Craig Vear]

In grappling with the concept of darkness, many artists were also discovering things as they themselves entered the dark. The following black page is by the poet Maura Dooley.

Not long after, I lost it –

Loveliest of things, hand-stitched,

So soft and subtle

I barely knew it was there.

Ask me now and though

I could tell you just when

And where I first saw it,

How it became essential is harder

And how it slipped from me

Harder still –

A last moment of neglect

Or something slower,

More insidious?

The way warp and weft,

A face, a voice,

Is sewn right in.

It is possession makes us careless.

This is highly evocative writing but we cannot understand its full significance until we find out what’s hidden, the story behind it—or within—which is this:

Using an anonymous rollerball gel pen because my lovely fine-nibbed Waterman fountain pen would not allow me to write small enough to fit my poem on the page. I like this rollerball, which has no markings on it whatsoever and was found in the pocket of an old coat. My mother had nightmares as a child because in the pockets of her father’s old Great Coat, which hung on the back of her door, she could feel the bones of soldiers who had died in the Trenches. When, finally, she plucked up the courage to look, she found her father’s pipe and a pen. (Dooley 2009)

What we learn from this and so many other artists’ statements is information that could never be gleaned from the works themselves. Collectively, they seem to express something about the creative process, the thinking that precedes— and runs into—execution, which is absolutely fundamental to the work, but is invisible. Frank Cottrell Boyce’s ‘page’ is a piece of slate, somehow attached to the paper. We read it initially as a tombstone, perhaps, but Cottrell Boyce writes:

Using a piece of slate from the Bwlch quarry, Manod because during World War II, the paintings of the National Gallery collection were hidden in a vast cavern under Manod Mountain. The slate comes from that cavern (technically it is called a ‘gallery’ which tickles me). I know the slate is grey but the cavern is unbelievably black when you’re standing in it and your torch goes out. I’ve always been intrigued by the idea of a totally dark cavern with brilliant, colourful, sensual masterpieces hidden in it. It gives me hope and makes me feel that if I root around in the darkest bits of my brain my fingers might just brush against the edges of a secret masterpiece. (Cottrell Boyce 2009)

Cottrell Boyce writes for children, and for the screen. (It is not widely known that he wrote the screenplay for the Tristram Shandy film, A Cock and Bull Story (2005), as he fell out with the director, Michael Winterbottom. The credit went to Martin Hardy, a name that bears clear similarity to Tristram Shandy with the s’s removed.) He was also the scriptwriter for the London 2012 Olympic opening ceremony, which surprised a lot of people with its poetic structure. Writing in The Guardian the day after the ceremony, he revealed how various personal things had made their way into the show, including the town motto of St Helens, where he was educated: ‘Ex Terra Lucem’, ‘out of the ground comes light’.

On the Poetry Archive website, Cottrell Boyce writes:

For all its noise and technological innovation, the show was nourished from its earliest stages on the quietest and most ancient of art forms – poetry. We worked for the first year in a little room in Soho which we plastered with pictures and poems. The show opened with Caliban’s speech from The Tempest, and with the equally haunting ‘found poem’ – the Shipping Forecast – both spoken over a tableau inspired by Blake’s ‘The Echoing Green’. The song that ushered in the Olympic torch used Auden’s phrase ‘affirming flame’ to describe the beautiful Thomas Heatherwick cauldron. The official programme doubles as a poetry anthology – with its selections from Carol Ann Duffy, Milton, and from Heaney’s ‘The Cure at Troy’ – which became a kind of manifesto for us. (Cottrell Boyce 2012: n.pag.)

On one level this is saying that poetry was an inspiration. On another, it is suggesting that the whole show was a poem of sorts, experienced by some 900 million people worldwide. Even if we take a step back from such a claim, those 900 million people were nevertheless experiencing something constructed like a poem, and with numerous ‘real’ poems twinkling within the dark of its one spectacular night.

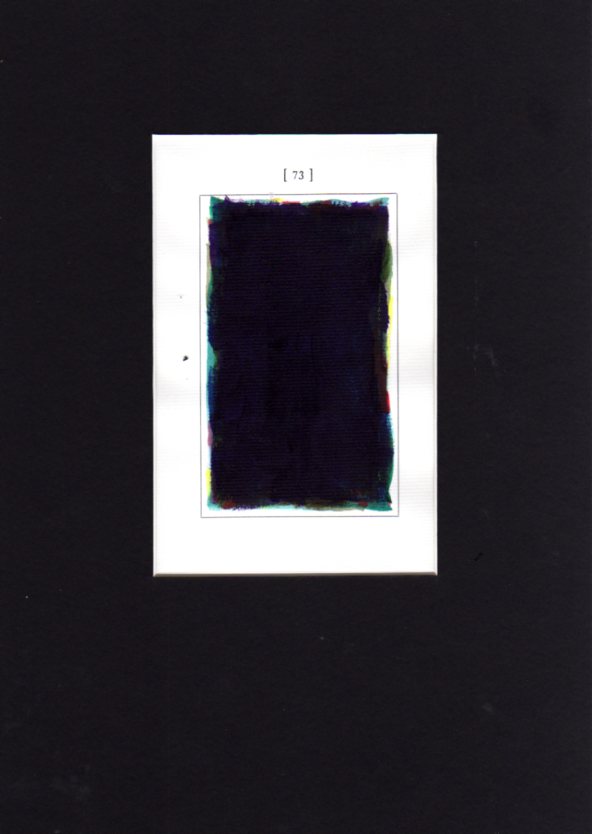

Returning to the black pages, there are many others that make a point about the colours contained within the apparent dark. Tony Whishaw said of his:

By using several layers of red, green, brown, blue, yellow and purple, I hoped to absorb as much light as possible and make a black – without using any black at all. Some of the layers have been left visible at its edges to give a vibrancy to what I hope appears to be a black void.

[Figure 8: BP#26, Tony Wishaw]

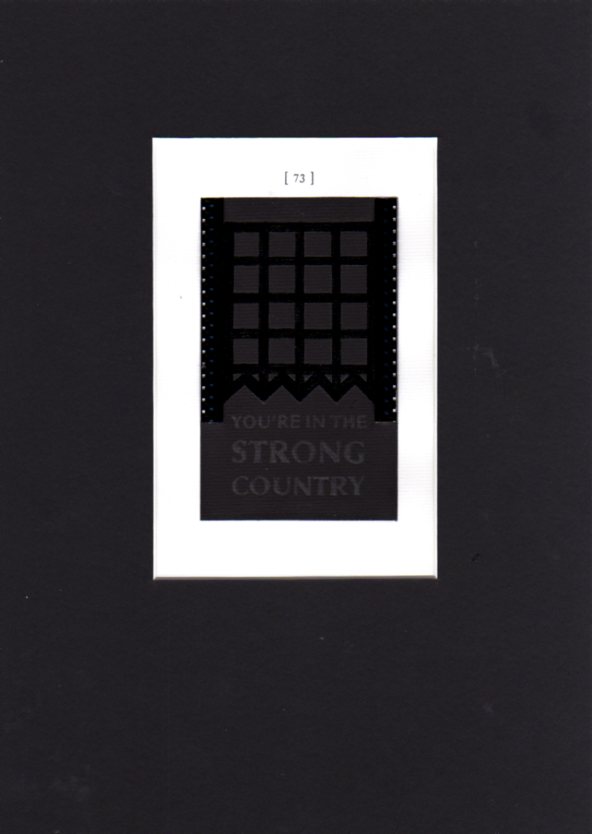

My own contribution is another example:

Using ink, acrylic & enamel paint, 8mm celluloid film and pencil [...] the background black is a double darkness, ink (marking out but then obliterating two names) covered over with an acrylic found in my mother’s old painting box. As a further layer, I have added the enamelled portcullis logo of Strong & Co. of Romsey, the brewery that employed my father for all his working life. My mother also worked there with him in their later years. The side chains of the portcullis are made of 8mm film. These almost black strips in fact contain a whole world of light – the final filmed images of my father, parking his (company) car in the drive of the home where I grew up, and which was then sold after he died in 1976. My mother died just four years later. Each film/chain forms a continuous loop on the reverse of the black page. The slogan ‘You’re in the Strong Country’ accompanies the logo. As with a tombstone, where the words tend to weather away, the text here is similarly frail. The typeface mimics chiselling but the letters are laid on as a mere pencil sheen.

[Figure 9: BP#38]

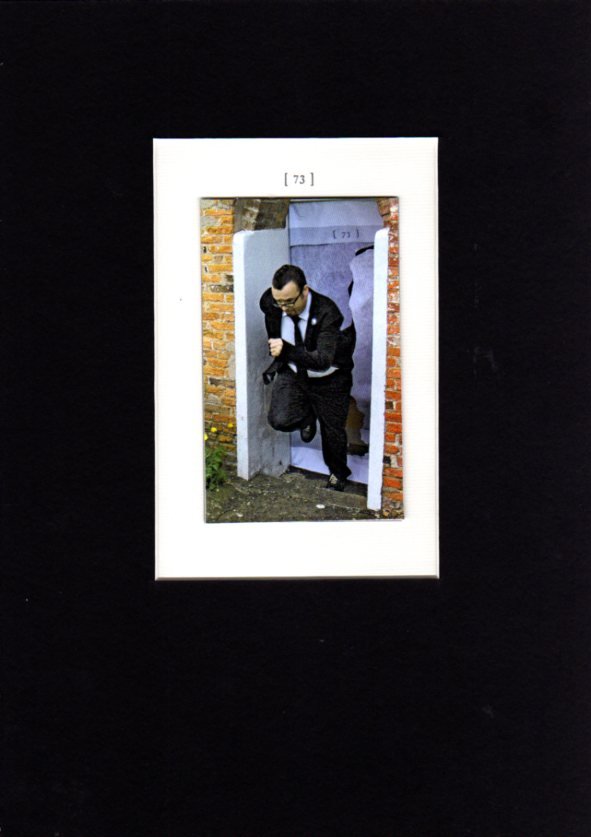

The darkness presented aims to allow the viewer to explore, to find a way in; the portcullis doorway is significant in this respect. The Black Page catalogue features a number of other depicted doorways, in the works by Madeleine Bunting, JM Coetzee, Jon McGregor, and Simon Morris—whose work in its exhibited form was a video projection, with the figure (the artist) bursting through a paper page fixed over a Shandy Hall doorway.

[Figure 10: BP#58, Simon Morris]

These various doorways suggested the title of this essay, which refers to Seamus Heaney’s poetry collection, Door into the Dark. In that book, there is no title poem as such, the phrase occurring instead (and rather appropriately) within one of the poems, ‘The Forge’. The effect is to draw even more attention to this poem, with both its actual title and the phrase within each gaining extra metaphorical weight.

The Forge

All I know is a door into the dark.

Outside, old axles and iron hoops rusting;

Inside, the hammered anvil’s short-pitched ring,

The unpredictable fantail of sparks

Or hiss when a new shoe toughens in water.

The anvil must be somewhere in the centre,

Horned as a unicorn, at one end square,

Set there immoveable: an altar

Where he expends himself in shape and music.

Sometimes, leather-aproned, hairs in his nose,

He leans out on the jamb, recalls a clatter

Of hoofs where traffic is flashing in rows;

Then grunts and goes in, with a slam and flick

To beat real iron out, to work the bellows.

(Heaney 1969: 19)

This is a poem—and a book—that has been inspirational. The former British poet laureate, Andrew Motion, wrote in The Guardian how ‘Door into the Dark opened the portals to a different future’ (Motion 2014: n.pag.). He understood for the first time what poetry could be:

The squelch and slap of the writing; the beautiful interplay of vowels and consonants (which carried Heaney’s voice into my ear long before I ever heard him speak); the connections between past and present […] the narrative anecdotes [...] as gripping as a short story; the warmth of the heart at work.

Returning to the dark doorway of my own black page, I am pleased that the editor of my selected poems (2015) agreed to include the image at the back of the book, and it appears at the end of the contents list as if it is another poem.

The original artwork was sold in the auction, so to publish it is partly to give it a continuing life, but it is also has a crucial relationship to one poem in the book that effectively takes the reader into the black of the page. The poem, ‘Home Movies’, relates to my father’s death—and the ciné film footage that captured some of his last days.

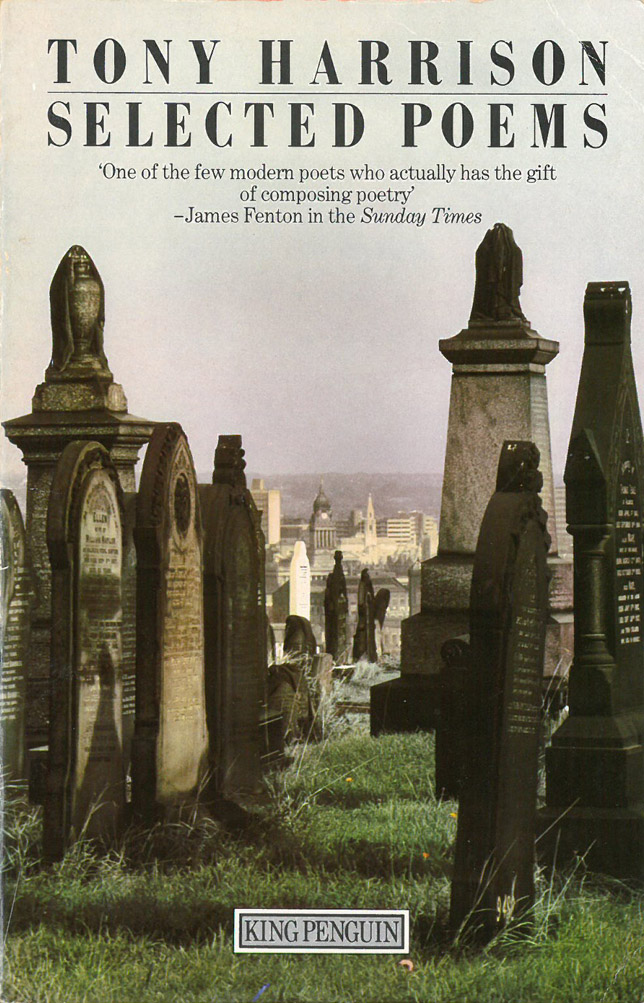

To read the poem is now the only way into the strips of film assembled in the portcullis of the black page. (It would be extraordinary if the owner of the artwork decided to dismantle it in order to see what lies within the film.) The work is now only accessible as a flat image. You cannot, for instance, see one key aspect of its construction—how the strips of film were threaded through the page and joined on the back so that they were continuous. Another poem informed my thinking on this, Tony Harrison’s ‘Continuous’ (1984: 143). It is a poem in memory of his father, and refers not only to the looped tape at his funeral but also to the old practice of cinemas screening continuous performances. Interestingly, the particular film that is mentioned in the poem is James Cagney’s White Heat, a ‘blinding light’ within the dark.

My copy of Harrison’s Selected Poems (1984) has on its cover the grave stones in the Leeds cemetery where Harrison’s father is buried, some of the tombstones themselves like black pages. [See Figure 11] When his family grave was defaced by hooligans, Harrison wrote the long poem, V, which is itself now commemorated on the gate into the cemetery [Figure 12]. Poetry has thus become part of the fabric of the surrounding world.

[Figure 11: Cover of Tony Harrison Selected Poems]

[Figure 12: Gate at Leeds Cemetery]

In compiling my own selected poems, I included not only ‘Home Movies’ and the Black Page, but also a newer poem that revisited elements of ‘Home Movies’, aiming for a deeper, more immersive journey into dark. This is the end of the poem, ‘This and That’, about clearing out a shed:

I’m lying here in the dark, shifting things

from those darker corners where darkness

warps into something darker still. Hung

on a rusty nail is a rust-coloured jerkin

that’s seen it all – and more. I slip my arms

through the stiff leather, walk to the clearing

at the top of the woods where a bonfire

still smoulders. One by one, I crumple papers

and release them, watching how they

open again, bright flowers, before curling

in on themselves as flakes of black;

the documents of a life, all that –

and then this, sent up in smoke.

(2015: 65)

The strategy here (whether successful or not) is to reach for illumination through the extremity of darkness. This connects to Mantel’s title/phrase, ‘Beyond Black’: The novel is partly about a psychic ‘going beyond the grave’ but also a character going into the darker recesses of memory, where things can’t be banished, or as one character says: ‘Not unless you could get the inside of your head hoovered out.’ As Terence Rafferty commented in The New York Times (2005): ‘Hilary Mantel’s humor, like Flannery O’Connor’s, is so far beyond black it becomes a kind of light.’

If we consider the beginning of Heaney’s ‘The Forge’, the words ‘All I know’ speak of total immersion. Everything outside, the flashing traffic etc., is by comparison banal. In the spirit of Sterne’s sidestepping from one medium to another, I shift here to mention the painter Mark Rothko, at the height of his fame when Heaney was writing. Rothko’s concept of his paintings ‘defeating the walls’ is a complex one, but one of the things it suggests is the artwork as a doorway or portal through the banality of the wall. And Rothko’s paintings seem to aim for a deeper and deeper darkness in order to achieve that immersion.

A visual artist renowned for his exploration of the portal is James Turrell (whose work was featured in a retrospective at the National Gallery of Art in Canberra at the time this paper was delivered). Photographs of his Skyspace creations at Roden Crater in Arizona are suggestive of a James Turrell black page. In another Skyspace, Agua de Luz in Yacatán, Mexico, Turrell has tunneled down to an underground natural limestone well, managing to find extraordinary reflections of light way beyond the point where one would think it possible. The visible light is reflected off water, and only happens twice a year, making the experience—in addition to its many other qualities—a poetry of patience.

It is partly the meditative quality of these images that chimes so strongly with the Black Page project, but also the idea of light and dark each being present somehow in the other, nowhere encapsulated better than in Patrick Keiller’s black page made of soot—from a candle.

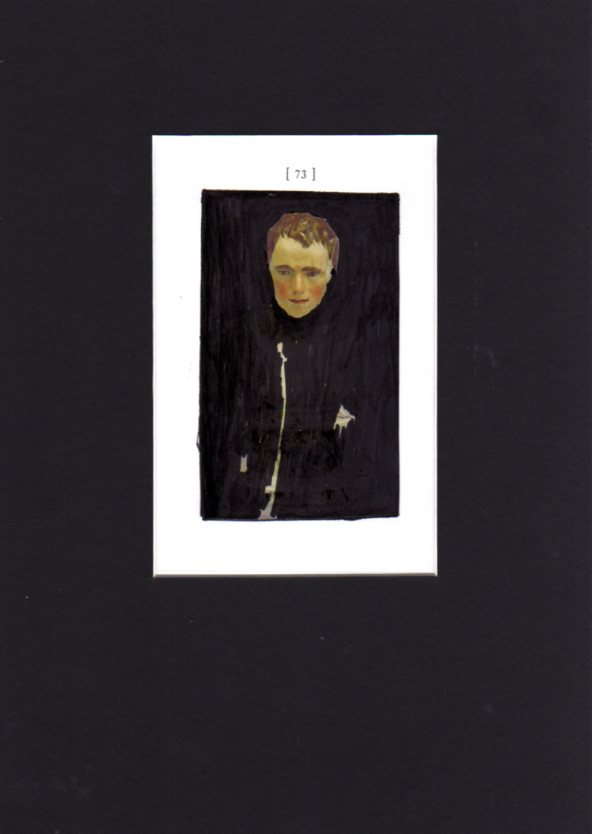

The transformation of a candle into soot involves the process of time. Javier Marias examines the process from a different perspective, allowing a human figure to (re)emerge from the memorial black. As Maria writes: ‘nothing ever perseveres, not even blackness, so it is normal that after 250 years the black in the Black Page is beginning to show something or someone.’ We are a long, long way here from ‘splat’.

[Figure 13: BP#22, Javier Marias]

On 28 November 2014, I read that the Sydney Daily Telegraph had ‘retired’ its back sports page, giving it over to a black page marking the death of cricketer Phillip Hughes. This was a remarkable editorial decision, but as with some of the black pages in the exhibition, the Telegraph’s black page did not quite trust its own concept; it included not only the words, ‘Vale Phillip Hughes’, but also an image of the man with his bat (and a bar code). Without the image of the man, the page would be more meditative, and we would bring to it (if we are cricket fans, certainly) our own, individual memories of that sportsman’s achievements, also perhaps other people’s sporting achievements, those of family and friends.

[Figure 14: ‘Vale Phillip Hughes’

A couple of days later, a crowd at Twickenham in England gave Hughes not a minute’s silence, but a spontaneous minute of applause. Just as I have described darkness and light as strangely coexistent, so too here are silence and sound seemingly interchangeable for a single expressive purpose.

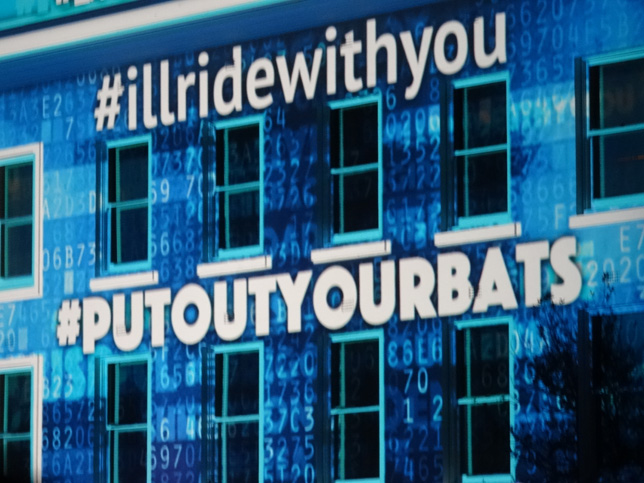

At Canberra’s Enlighten Festival, 2015, another Phillip Hughes commemoration took place: a tweet of memorial light, seen once darkness had fallen, projected onto Old Parliament House.

[Figure 15: ‘put out your bats’]

There have been all sorts of tweeting poetry projects, but this seemed somehow more authentic and original, more unexpected, more poetic; poetry without its label. Similarly, those perusing the Black Page exhibition suddenly found themselves reading a poem without knowing it, and were, perhaps, affected by it with particular intensity as a result.

Sterne’s black page is frequently referred to as a visual ‘intervention’ in the text, which of course it is, but it is not just cleverness, it is also struggle; it is acknowledgement that mastery of one particular medium is not always enough, that the medium itself is not enough. The artist sidesteps, as if in frustration at his or her habitual medium, and the material presented gains force as a result. Such restlessness may seem at odds with the notion of memorial, but is fundamental to adventurous art. Some of the black pages play a little safe, their artists perhaps focused too exclusively on the page/image, rather than its extraordinary point of departure from the text; they make no sidestep from their own known practice. The black pages that embody a more restless courage are for me the more successful (and I would cite Craig Vear’s, Figure 7, as an example). They reflect Sterne’s brand of radical creativity and embrace the unknown. The black page is not simply a statement of termination but an anguished meditation on loss—a darkness that might equally be a blinding light.

Celan, P (1948) ‘Todesfuge’, translated as ‘Death Fugue’ by J Rothenberg 2005, at https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/death-fugue (accessed 22 March 2016)

Cottrell Boyce, F 2012 ‘A Tour of the Archive with Frank Cottrell Boyce’, The Poetry Archive, at http://www.poetryarchive.org/guided-tour/tour-archive-frank-cottrell-boyce#sthash.5kNKjvF5.dpuf (accessed 22 March 2016)

Harrison, T 1984 Selected Poems, Harmondsworth: Penguin

Heaney, S 1969 Door into the Dark, London: Faber and Faber

Lynch, T 2008 An Interview with Writer and Undertaker, Thomas Lynch by Ben Israel and Sarah Sala, The Oleander Review, 2, p.53

Lynch, T 2011 Walking Papers, London: Jonathan Cape

Motion, A 2014 ‘Door into the Dark opened the portals to a different future’, The Guardian, 18 August, at http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/aug/17/door-into-the-dark-seamus-heaney-andrew-motion (accessed 22 March 2016)

Munden, P 2015 Analogue/Digital: New and Selected Poems, Sheffield: Smith|Doorstop

Rafferty, T 2005 ‘Beyond Black’: Demons Revealed’ New York Times, 15 May, at http://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/15/books/review/beyond-black-demons-revealed.html?_r=0 (accessed 22 March 2016)

Shapcott, J 2010 Of Mutability, London: Faber and Faber

Wordsworth, W 1975 [1807] Poetical Works, Oxford: Oxford University Press