This paper looks at poetry as a response to the bushfires that devastated Victoria on February 7, 2009 and its capacity to ‘hold’ what cannot be said, and yet must be said, when no other language will do. In the disaster there is trauma and transformation. Yeats says it best: that out of the darkness a ‘terrible beauty’ is born (‘Easter, 1916’).

Keywords: poetry—memorial—bushfire—disaster—trauma—transformation—Black Saturday—Maurice Blanchot—Writing the Disaster

from South in the World

Thinking about Black Saturday from the Swiss Alps

You who saw the firestorm’s rage

and somehow managed to escape

the flames that took whole families

and (must we say it?) children,

babies. I could list them forever:

the petrified horses, the dazed wombats,

the kangaroos in an incendiary pack.

Did the Green Christ see them

and who can answer all of this?

Whom then can we blame?

Angels were of no help that day,

flying in on burning wings

and crashing to the ground.

Few who found the ragged heaps

saw the mark of their divinity.

Some took them home to bury

in their burnt-out yards.

But angels are no match for fireballs,

their garments a trap for embers.

And anyway, didn’t we lose our need

for angels long before these fires?

For whoever has seen them,

few believe.

Those of you who returned to see

the things no one should ever see,

corpses in cars and prone in baths;

you whose names are listed and filed

in the databases of council shires

as survivors of those deceased by fire;

you who endured that unendurable night,

praying that the dead were still alive:

is it too much to grasp the greening of things

that were black and charred?

The body burnt and pierced floats

ever skyward. Keep your eyes on it.

(Jacobson 2014: 27-29)

The 2009 Victorian bushfires, also known as Black Saturday, occurred on February 7 2009 during extreme bushfire conditions and resulted in Australia’s highest ever loss of life from a natural disaster. Firestorms claimed 173 human lives, injured 5000 people, destroyed 2029 homes, killed countless pets, livestock, and native animals, and burnt through over 4,500 square kilometres of land.

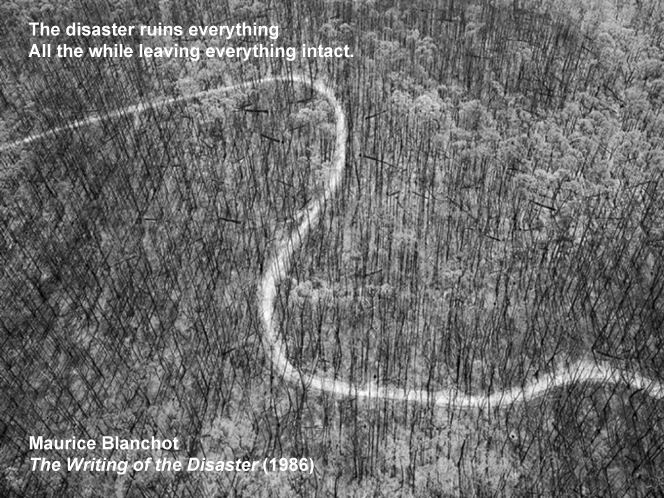

‘The disaster ruins everything. All the while leaving everything intact’, writes Maurice Blanchot in his seminal work on 20th century catastrophes, Writing the Disaster (Blanchot 1986 [1980]: 1).[i] His fragmentary philosophical text explores the paradox of disaster, which shatters the exterior world while our internal map of it remains intact, imprinted with patterns that no longer exist. Such was the experience of those who survived Black Saturday.

Gradually and suddenly, the disaster that was Black Saturday arrived. Survivors will tell you how their water tanks started bubbling, swimming pools filled with ash, how birds fell from the sky, and the sky turned black. When they try to describe the enormity of the firestorm, they start reaching for similes and metaphors. They say, frequently, generically, that it was ‘like 1000 jet turbines… like living in a war zone… like living on another planet.’[ii]

Bushfire survivors seek words to speak the unspeakable and say the unsayable. Life and their memory of it no longer match, the people they love and know so well suddenly vanish.[iii] And the language that best articulates this—the language of disaster—is, I want to argue, the language of poetry.

The disaster, in and of itself, is impersonal in its brutality. In the case of ‘natural’ disaster, it is seemingly without meaning. Blanchot writes, ‘The disaster is not our affair and has no regard for us; it is the heedless unlimited. It cannot be measured in terms of failure or as pure and simple loss’ (1986: 2). For those impacted by a disaster they do not understand, poetry can facilitate meaning where meaning is absent. Nietzsche said, ‘He who has a Why to live for can bear almost any How’ (Nietzsche 2012: 3). At the least, poetry contributes towards healing. At its best, it offers the possibility of transformation. Trauma psychologist Rob Gordon, who has worked with many Black Saturday survivors, says recovery (if one ever really recovers) can take several years, a decade, or many, many more.[iv]

It takes time to heal, and time to write a poem. Healing from disasters such as bushfires is often not possible until the busyness of re-establishing the shape of daily life finally slows its frantic pace. It is only when the funerals are over, the houses rebuilt, and the pattern of ordinary living resumed, that the rebuilding of the interior self can begin.

This is the hardest work: to re-member what has been dismembered, to re-fence the internal landscape of the psyche (as the land is re-fenced to contain surviving livestock), to re-cover the traumatised psyche and offer it protection (as people wrapped themselves in wet woollen blankets as fire shields). It is also disturbing work: to allow the psyche to fall into the void, held together by all of those hyphens. Blanchot calls it: ‘Night; white, sleepless night… the night lacking darkness, but brightened by no light’ (2). No wonder survivors do the external work first.

What can fill this unlit pause? There is silence of course. Blanchot writes, ‘let the disaster speak in you, even if it be by your forgetfulness or silence’ (4). And yet we are verbal creatures. We make sense of our world through language and images that connote language. In this repect, nothing is denotative, everything connotative. The disaster calls for metaphor; symbolic language that stands in for the thing the disaster has taken. Yeats understands this in ‘Easter, 1916’, where a ‘terrible beauty’ is born out of darkness (Yeats 1991: 124). For what else might de-scribe disaster and yet, at the same time, honour it in new and transformative ways?

If poetry, in particular the poetry fragment, is often the language of memorials,[v] perhaps it is because it is adept not at the task of remembering in order not to forget, but to un-get from the mind the intensity of what has happened. And perhaps only then is it possible to go on. As Rilke writes, ‘Let everything happen to you: just keep going. Beauty and terror. No feeling is final’ (Rilke 1996: 88).

The community members who participated in the poetry workshops I led in the small town of Whittlesea at the foot of Kinglake (where many lost their lives) could scarcely bear to remember what happened on Black Saturday. Many would much rather forget. All of them were fire-affected. All had suffered great losses. But remember they must. They had gathered with me to create wording for a permanent bushfire memorial to the twelve local residents in the area, well known to them, who had perished in the fires.

The memorial is where remembering takes precedence over literary merit. The poetry produced for memorials is not destined for literary journals or awards. Rather, it is composed of personal fragments that piece together a collective story of a community impacted by disaster. Below is a small sample of lines written in the community workshops for the Whittlesea Bushfire Memorial, which may now be viewed on the completed memorial situated in Tourrorong Reservoir Park, Whittlesea.

Note that these lines do not comprise one single poem—all except the last are single line fragments written by different people. They are written by rural farm folk, most of whom do not have tertiary degrees and are not participants in the world of art and culture. Yet the lines have, to my eye, a sense of yearning to express their experience of trauma in a language that honours and authenticates it. All of these people lost loved ones—friends and family—in the fires. Many lost entire homes and everything in them.

Whittlesea Bushfire Memorial Fragments

How can I tell my children their friends are gone?

So many funerals, so much crying.

At night the stars still shine.

Some days, it’s not all sad.

‘Afterwards’ is someone I’m working on being.

How wonderful it is to have you all still here within me.

The last line of this sample is actually part of a short poem, written by a father who lost absolutely everything. Running through the firestorm with his family, his wife and four year old daughter collapsed. Seeing no choice but to leave them behind, he struggled to carry the two younger children onwards towards a nearby dam. But he, too, was close to collapse. His feet had melted to his shoes. He placed his three year old son on the ground and, in one last effort to save his baby daughter, hurled her over fence in the direction of the dam. The father then went back to find his son but was unable to locate him in the thick smoke and fire. He retrieved his sole, badly burnt infant and walked, somehow, along the road, calling for help until a neighbor saw them. The baby girl died in hospital. Only the father survived, waking from a coma to learn he had lost everyone who was dear to him. Surgery would later remove his leg.

Several years after the fires, I receive a four line poem from this man as a contribution to the bushfire memorial project. This poem is now inscribed on a smaller memorial located on the Whittlesea-Yea Road that winds up the mountain to Kinglake. ‘How wonderful it is to have you all still here within me’ writes the man who lost everything (Personal comm. 2013).

The German philosopher Walter Pater said that all art aspires to the condition of music. In a sense, we might also say that all suffering aspires to the condition of poetry. I am thinking of Yeats in his poem ‘The Circus Animals’ Desertion’ when he writes, ‘Now that my ladder’s gone, / I must lie down where all the ladders start / In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart’ (Yeats 1991: 224). I am thinking of a poem by Michael Leunig that begins, ‘When the heart / Is cracked or broken / Do not clutch it / Let the wound lie open’, and goes on to suggest that if we remain receptive to our suffering, we can transform it (Leunig 1999: unpaginated).[vi]

I would argue that what Yeats, Leunig and perhaps most artists suggest is that we don’t have to approach closure so rapidly that the healing is forced; rather, that we might sit in the wound itself, in that difficult place where there are more questions than answers, in what Keats calls a state of ‘negative capability’ (Keats 2007 [1899]). In doing so, we might transcend and reframe the experience of trauma. Of course, this is easier said than done, art and life being very different things. But this is what art makes out of suffering.

‘Thank you,’ said the man who had lost everything in an email to me after I had helped him shape his poem for the memorial. ‘That which was scratchy and rough is now smooth to read’ (Personal comm. 2013). I don’t know much about how people get over things. I don’t know how someone can hold that much loss, only that poetry is helping him to heal.

Memorial poetry is the language of gaps and fissures, fragments and cracks. Trauma psychologist Rob Gordon notes that gaps and pauses in stories told by bushfire survivors are significant: ‘The pause indicates a point in the narrative of intense threat – they pause at a peak of arousal’ (Gordon 2007: 15). Gail Jones, in an essay that celebrates the fragment, writes in honour of language that falls into the gaps which, in doing so, becomes ‘an allegory of loss and incomplete recovery, of the… failure to fully figure’ (Jones 2006: 12).

The anguish of disaster is the inability of words to articulate the immensity of this great, gaping loss. It is the terrible pause in which the bushfire survivor dwells years after the disaster in that moment of untreated memory (for there will always be moments) neither ‘before the fires’ or ‘after the fires’ but somewhere in between. It is the cleft of rock where, in one of my bushfire poems, the dragonfly hovers, caught in a liminal space between before and after (Jones 2014: 85).[vii]

After the disaster, there was good fire and bad fire. All flame was threatening, and Prometheus bound. The only good fire was the one keeping people warm as winter approached, huddling around fires lit in 44 gallon drums before retreating to tents and vans. Good fire keeps the wild beasts at bay, except in this case the wild beast was the firestorm, its story told around the site of the good fire at night.

‘Disaster’, from the Latin dis (expressing negation) and astro (star), means literally ‘an unfavourable aspect of a planet star’: literally, ‘bad star’. Dis is also an inflected form of deus, dis pater was God of the Underworld. In reflecting on Black Saturday, we are indeed in the territory of great darkness. We are underground in the realm of the dead, where no light leaks but where light nevertheless may be found. Suffering is not that which we undergo but, rather, that which goes under. We are with Persephone, journeying eternally down and then up again towards the mouth of light.

‘Girls and Horses in the Fire’ (2014: 25 ) is an elegy for two sisters on the cusp of adult life, glowing with promise, who died on Black Saturday. The poem was written in the first week after the ‘bad star’ that was the disaster. I wasn’t aware of the etymology of this word at the time. Even so, the poem lifts these girls out of the firestorm and places them in the sky, attached to the stars to which they rightly belong. Starlight as fire, burning radiant in the darkness.

Girls and Horses in the Fire

Kinglake, Black Saturday 2009

Nothing will come between them,

those girls and their horses;

not wind or rain, nor pillars of fire.

If a hand should flick a match

amongst leaves, or trunks implode

with the weight of heat, or lightning

blast the wasted trees, still they’d run,

these girls, through conflagrations,

wreathed by flames and embers.

Girls who run towards horses in fire,

may you find your home in the equine stars:

Pegasus, Equuleus. Hush, sleep now.

[i] All future references to Maurice Blanchot’s Writing the Disaster text will be in-text page numbers.

[ii] See A Hyland (Kinglake 350) and R Kenny (Gardens of Fire) who depict this experience of Black Saturday.

[iii] This is not to be confused with what Theodor Adorno famously said: ‘To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’ (Adorno 1983 [1951]: 34) regarding poetry written in response to sociopathic catastrophe. Adorno later revised this to say: ‘Perennial suffering has as much right to expression as a tortured man has to scream; hence it may have been wrong to say that after Auschwitz you could no longer write poems’ (Adorno 1973 [1966]: 34).

[iv] The long-term impact of trauma as a result of natural disasters is well-documented. For a comprehensive bibliography see R Gordon, ‘Thirty Years of Trauma Work’ (Gordon 2007).

[v] The Strathewen Bushfire Memorial, Melbourne, includes poetry fragments by Black Saturday survivors written under the guidance of author Arnold Zable. Inscriptions contributed by 2003 survivors for the Canberra Bushfire Memorial also read ‘like’ poetry.

[vi] While outside the scope of this essay, there is a long history of Australian poetry on the subject of bushfires: for example, Judith Wright, Francis Webb, John Kinsella, Morgan Yasbincek, Sarah Day, Geoff Page, Les Murray and John Jenkins, though less collaboratively. Poets who have written specifically about Black Saturday include Fiona Wright (Knuckled), Jordie Albiston (VIII Poems) and myself (South in the World). See also ABC Radio’s Poetica Bushfire at: http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/poetica/2012-07-28/4112790.

[vii] Indigenous methods of relating to fire in Australia and the disrupted ancient history of indigenous fire management assists in the evolution of our ecological understanding and land management practices regarding bushfires. While not necessarily at the forefront of survivors’ minds, this is in turn affecting how people might combine modern methods with ancient knowledge to more safely live in the bush. See T Flannery (The Future Eaters), B Gammage (The Biggest Estate on Earth), T Griffiths (‘The Language of Catastrophe’) and R Kenny (Gardens of Fire).

Adorno T 1983 [1951] ‘Cultural Criticism and Society’, Prisms, trans. S and S Weber, Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 17-34

Adorno T 1973 [1966] Negative Dialectics [Negative Dialektik], trans. E Ashton, New York: Seabury Press

Albiston, J 2013 VIII Poems, Melbourne: Rabbit Poetry Series

Blanchot, M 1986 [1980] The Writing of the Disaster, trans. A Smock, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press

Bushfire survivor, 26 Nov. 2013, personal communication

Flannery, T 2002 [1994] The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australasian Lands and People, New York: Grove Press

Gammage, B 2011 The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia, Sydney:

Allen & Unwin

Gordon, R 2007 ‘Thirty Years of Trauma Work: Clarifying and Broadening the Consequences of Trauma’, Psychotherapy in Australia, May, 12-19

Griffiths, T 2012 ‘The Language of Catastrophe: Forgetting, Blaming and Bursting into Colour’, Griffith Review, Issue 35 Autumn, 46-58

Hyland, A 2011 Kinglake 350, Melbourne: Text Publishing

Hyland, A 2014 South in the World, Perth: UWA Publishing

Jones, G 2006 ‘A Dreaming, A Sauntering: Re-imagining Critical Paradigms’, Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature 5, 11-24. See also M Foucault’s essay, ‘Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias’ 1993 [1968], on which Jones’ essay draws, Architecture Culture 1943-1968: A Documentary Anthology, eds. J Ockman & E Eigan, New York: Rizzoli

Keats, J 2007 [1899] The Complete Poetical Works and Letters of John Keats, Cambridge Edition. Montana: Kessinger, 277.

Kenny, R 2013 Gardens of Fire: An Investigative Memoir, Perth: UWA Publishing

Leunig, M 1999 ‘When the heart’, The Prayer Tree. Sydney: Harper Collins

Nietzsche, F 2012 [1889] Twilight of the Idols, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

Poetica Bushfire, 28 July 2012 (accessed 11 July 2015) with poems by J Albiston et. al. at: http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/poetica/2012-07-28/4112790

Rilke, R M 1996 [1941] ‘God speaks to each of us as he makes us’, Rilke’s Book of Hours: Love Poems to God, trans. A Barrows & Jo Macy, New York: Riverhead

Tranter, R 8 November 2009, ‘The Writing of the Disaster: A Reflection on the French Writer’s Seminal Work’, http://www.apieceofmonologue.com/2009/11/maurice-blanchot-writing-of-disaster.html (accessed 10 July 2015)

Wright, F 2011 Knuckled, Melbourne: Giramondo

Yeats, W B 1991 [1939] ‘The Circus Animal’s Desertion’, W. B Yeats: Selected Poetry, ed. T Webb, London: Penguin

Yeats, W B 1991 [1920] ‘Easter, 1916’, W B Yeats: Selected Poetry, ed. T Webb. London: Penguin