This collaborative paper offers three interleaved perspectives on how the medium of comics can change and refresh our perception of narrative making, reading and analysing. Our growing understanding of the unique relationship between space and time in comics, and the defamiliarising effect of visualising narrative conventions in comics, has enriched and altered the way we approach creative writing practice. Our common ground is the creative space of the Graphic Narratives classroom, a place where students and staff encounter images alongside words and experiment with the possibilities and limitations of each.

Keywords comics — creative writing — graphic novels — teaching — multimodal narratives

Introduction

We are three writers and researchers learning to teach the image. We approach comics from different backgrounds and engage the medium in different ways, but our point of convergence is Graphic Narratives, a fourth-year subject developed by Dr Elizabeth MacFarlane at the University of Melbourne. Liz founded Graphic Narratives in 2011, when it was Australia’s first tertiary-level subject devoted to the study of the comics medium. Each year students create a minicomic which they then have the opportunity to swap or sell at an annual showcase event open to the public. With graphic novelist and academic Dr Pat Grant, Liz co-directs the Comic Art Workshop, Australia’s first artists’ residency dedicated to supporting major comics projects in progress. Bernard Caleo has taught comics making skills as part of Graphic Narratives, and also at primary and secondary schools. He edited and published the giant romance comics anthology Tango from 1997 to 2009, and made the feature documentary Graphic Novels! Melbourne! in 2012 with filmmaker Daniel Hayward. His ongoing project is to investigate possibilities for performing comics. Dr Ronnie Scott guest lectured, then tutored, then coordinated Graphic Narratives in various years and has since integrated comics into his Media & Communication Honours Lab and his undergraduate Nonfiction studios in the Creative Writing program at RMIT University. He has also published comics criticism in national venues and edited comics for international literary magazines, as well as publishing scholarly research on comics.

How has teaching and researching graphic narratives in the context of a creative writing program changed our practice? We sought to make this paper because we are learning through practice. ‘Make’ is the right verb: although our contributions take the form of grabs/flashes/panels of text, chapters of continuous text, and comic strips, we decided to treat text as copy, pagination as creative tool, and collaboration as material and graphic. This provisional space, where text behaves textually but also graphically, and graphics contribute to the reflective purposes of the text, speaks to our experience in graphic narratives — a space to which we bring our experience as writers and researchers, and a laboratory in which our writing and research shifts.

Because comics is a newer medium than prose, poetry or scripted text (and so is its scholarly discourse), it creates opportunities for writers and researchers to experiment with ways to match meaning to form. For this reason, we’ve tried to treat this paper as provisional and playful — reflecting too the mindset of the creative writing researcher or student approaching a new form. A page of comics often works in an economy of gaps, putting like and unlike things in dialogue with each other, as liable to work with juxtaposition and contrast as with sequence and flow. This creates what Liz thinks of as the ‘third space’: a dialogic encounter where text and image transform each other. In comics, the written word becomes image-like, and images can be read like a language. When reading and creating comics, there is an oscillation between perceiving the whole at once, and reading sequentially, that invites us to see each of these practices anew. Each of us has the sense that the concrete image gets at meaning more directly but less articulately. It’s ineffable. It’s not the kind of meaning you can speak easily about. It’s commonplace to consider the ways in which comics does and does not work as language (see Matt Saraceni 2003, Hannah Miodrag 2013); yet coming though a discipline that emphasises text, it’s the instantaneous that seems first to separate it from ‘Creative Writing’ — a shot-in-the-arm quality that has the potential to bring something new to our practices as researchers and writers. It’s seen before it’s understood; it’s read all at once: not as an idea about the thing but the thing itself (Stevens 1997).

1 Ronnie

The years I spent teaching into graphic narratives were also years I spent learning to write a novel. Coming from a background of writing essays and criticism, I found myself floundering in an omnidirectional stupor. It was like the part of your maths education, sometime in primary school, when you’ve been working in graphs with positive numbers along the X and Y axis, and suddenly, the lines start to distend backwards and down; behind the 0 are negative numbers, minus one to minus infinity; and with them, you realise that perhaps changing one digit in the negative zone causes lines in the positive zone to move as well. In other words, I could suddenly make things up out of nowhere, as opposed to picking and choosing things from texts and life; and this had implications for voice, tone, and structure, making familiar options feel suddenly new. Chief among the new affordances was metaphor. In one draft, I had a character try to figure out whether or not they had seen something they remembered seeing; they described the memory as ‘a school of quantum fishes moving swiftly out of view’. In subsequent drafts, the half-remembered event was removed, so the reference to the memory of the event was removed too. Later, a character — the subject of the memory — was involved in a disappearance and a drowning, an event which changed the tone of the story and thereby was removed. Later still, the event was restored as a ‘possible drowning’, which caused disturbance and disquiet, but was not a tragedy — something more in line with the tone of the original memory, where the point was to come up against the edges of the unknown. The idea of creatures underwater moved from metaphor to occurrence to something in between. In comics, where the same image might be used to define a character, event or location and to show us its atmosphere, meaning or mood, this in-between state, both positive and negative, is business as usual.

2. Bernard

3. Liz

First I say, ‘Think of an everyday process. Something that takes a number of steps to complete. Like making breakfast, or planting a seed, or repairing a bicycle tyre puncture’. I give each person a small pile of post-it notes and ask them to draw a picture of each step of the process.

When we are finished, we put our post-it note drawings aside and take a fresh sheet of paper. I ask everyone to think about a clear memory they have from their childhood or youth. ‘It doesn’t have to be a particularly meaningful memory (though it might be), just something that has stayed with you.’ We write down the memory using the same number of sentences as the number of post-it notes we drew on.

I turn on the document projector: an old but clever piece of technology that will project a piece of paper onto the wall using a mirror and light. The first person displays their first picture: a kitchen scene in which we see a woman and a young girl from behind at the sink. The girl is standing on a stool and washing dishes.

We hear: ‘I woke up, looked out of my window and saw a blow-up castle.’

In the next image, the girl hands a plate to the woman who takes it with her hand wrapped in a tea towel.

‘It was in the process of being deflated.’

The woman places the dried plate on top of a pile of other plates while the girl submerges a glass in the sink.

‘Slowly, the pointy tips of the castle bent onto themselves.’

The girl lifts the glass from the water and holds it aloft, upside-down, suds clinging to its sides. In the same image, the woman reaches to turn the volume knob on a radio which sits on the kitchen bench.

‘The castle became a soft shapeless mass; it took only a few minutes.’

The glass is in the dishrack and the woman is holding the girl’s soapy hands. They are both smiling. Movement lines show they are dancing to the musical notes that spring from the radio.

‘I’m still not sure if this is a real memory or a dream.’

The girl has pulled the plug from the sink and dangles it above the draining water. The woman lifts a stack of plates into a cupboard.

‘They folded it up until it fit into the back of a ute, and then the ute drove away and the field was empty.’

4. Ronnie

When I write a piece of nonfiction about comics, whether it’s formal academic scholarship, a profile, or a review, I first have to briefly outline what a comic is, whether this is mentioning that comics aren’t just for kids or returning to Will Eisner’s go-to idea of comics as ‘sequential art’ (Eisner 1985). The first week of Graphic Narratives at the University of Melbourne is devoted to ‘the problem of definition’, partly as a way of establishing the key terms we’ll use across the subject; partly as a way of introducing the history of comics’ changing cultural reception; and partly as a way of beginning to (productively) argue about what it is we’re making in the class and (less so) what we aren’t. Graphic Narratives students don’t usually argue about whether or not comics are just for kids; whether there’s a substantive difference between a comic and a graphic novel; or whether it’s fair that graphic novels refer to nonfiction comics too. Each year I’ve taught it, there is instead a formal sticking point: whether or not a single panel can be considered comics, even if it contains some comic-like things, like a style of drawing familiar from comics, speed lines, or word balloons. The room is divided. I love this discussion because it opens an aperture to further discussions, about how comics invite us to think about what’s there and what’s not. How long is the character ‘there’ for — as long as its word balloon takes to be read? If a word balloon contains ideas and time, how does it differ from a panel? Artists elide time between panels and rely on shorthand and inference, just as writers do between sentences; in both image and text, we can know what’s happened without being literally told. In comics though, these literal ‘showings’ and their implications are visually mixed up. So if a panel shows a pregnant moment, suggesting a future and a past, how strong does the suggestion have to be before we can say it’s in front of us?

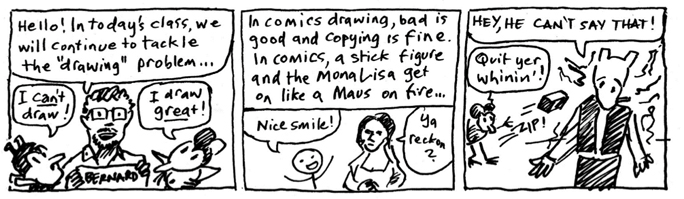

5. Bernard

6. Liz

We are quiet for a while after the reading. We ask: Where is the story happening? Is it in the words or in the pictures? Is the woman telling the castle story to the girl in the kitchen? Or is the girl the one who saw the jumping castle, perhaps that morning? Or is the memory someone else’s entirely? What is the relationship between washing the dishes and the slow deflation of a blow-up castle? We find threads between the plug in the sink and the plug in the castle. We talk about water and air being released.

In the narrative medium of comics, words and images may sit by one another in innumerable configurations. The words don’t necessarily describe the images; the images don’t necessarily illustrate the words. The term in use by scholars of narrative and education is ‘multimodal’, also the term adopted by the Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority in 2014 to expand the film category in the English Text List so that it could include graphic novels. Since the introduction of the multimodal category, Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1991) was the sole comics text listed for four years, and in 2018 Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis replaced it.

Tonal frisson has always existed as a technique in single-mode (monomodal?) texts – between, for instance, voice and content, or between narration and speech acts, or between mimetic and diegetic storytelling in prose novels. In multimodal narratives, the innate interplay between simultaneous narrative modes (image, text, sound, for instance) may be exploited to startling effect. As the deflating castle and the two people washing dishes unfolded in words and projected images, we found that the story could not be located in either mode, but somewhere else. Roland Barthes, writing about Crepax’s comics adaptation of The Story of O, says

It may be that eroticism (i.e., desire meeting an object) is never found in representation (the analogical image), nor even in description (the evoked image). When all is said and done, it may be that the eroticism in The Story of O occurs neither in what one sees nor in what one reads; it occurs in the universal picture, immanent in all language, which does not result from either image or discourse — the interlocution: it is because others speak words to O that she in turn speaks to them. (1985: 54–55)

My academic trajectory has taken me from Coetzee studies to Comics studies, and for a while this appeared to represent a stark left turn, but interlocution is the through line. How does the philosophical essayistic voice speak to the fictional metaphorical voice in books like Elizabeth Costello and Diary of a Bad Year? How does the scratchy cross-hatched image speak to the clipped erudite narration in the graphic novel From Hell? What happens in between? How wide is the aperture into which the reader may enter and co-create the text?

7. Ronnie

Even when you write to a plan, a shift happens in prose between a first draft, which you build by putting one word after another, and a draft that considers what happens in the first sentence alongside what happens in the tenth and the twelfth. The latter stage, rewriting and editing, almost feels more like reading — making connections between one page and another, and within the page too. In comics, where the eye moves both from left to right and up to down (in comics that use western narrative conventions) and in a freer pattern around the page guided by shapes, lines and points of interest, it’s easy to feel this tension between the whole of a narrative and its qualities of sequence; according to Andrei Molotiu, the tension between ‘sequential dynamism’ — comics moving forward — and ‘iconostatic perception’ — comics staying still — is responsible for a tension that structures comics reading experiences, obvious in abstract comics but underlying narrative experiences too. In a process of ‘harmonization and reconciliation’, ‘the two go hand in hand’ (Molotiu 2011: 93). When making comics, compositional choices often happen early on, rather than being applied and finessed retroactively; it’s harder to experiment on the page and then edit non-destructively. In a guest masterclass from Nicki Greenberg, students were fascinated — and I was fascinated — by her sketchbooks that showed how much ‘working out’ was done at the start of a project, followed by a stretch of execution that lasted many years. There’s space for improvisation, but the relationship of planning to practice stands in contrast with EL Doctorow’s likening writing to ‘driving a car at night: you never see further than your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way’ (in Plimpton, 1986).

8. Bernard

9. Liz

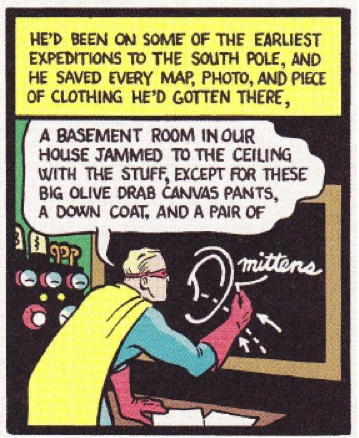

I introduce the memory-process exercise to students alongside a prescribed reading called ‘Thrilling Adventure Stories’ by American cartoonist Chris Ware. The comic is an exercise in exploiting the relationship between text and image: the pictures depict a Golden Age-style superhero-and-mad-scientist adventure tale, while the words tell a number of idiosyncratic first-person stories about a child’s memories of their grandparents, step-father and friends. The textual stories are not confined to the usual spaces for text in comics, namely narrative boxes or speech balloons, but slide into the drawn world. In one panel a yellow narrative box at the top describes how the narrator’s step-father had been on some early expeditions to the South Pole (see Fig 1).

The narrative box closes in the middle of a sentence, which then continues in a speech balloon below it, but still the sentence isn’t finished. The final word of the sentence, ‘mittens’, appears within the drawn part of the panel, written in chalk by the superhero character onto a blackboard, accompanied by an arrow pointing to an image of an ear. In the final panel of the same page, we understand the chalked image to be a diagram of the superhero’s plan to enter the villain’s brain via his ear. It’s easy to miss the word ‘mittens’ altogether, accustomed as we are when reading comics to separate textual language from visual language, and the extradiegetic world of narration from the diegetic world of a story unfolding. Ware’s exercise draws attention to the absurd not just in the comics medium, but in storytelling itself, in the same way that Magritte’s text-and-image exercises draw attention to the absurd not just in painting, but in semantics. In deconstructing the accepted conventions and limitations of narration, speech and mimetic action, Ware’s comic challenges the reader to defamiliarize themselves with what they know about how storytelling works. Who is the disembodied voice of the extradiegetic narrator, for instance, and how could it possibly be narrating an event as it unfolds? The visual layering of comics emphasizes the often impossible simultaneity of narrative conventions.

10. Ronnie

Materiality in comics influences not just how a work is received — i.e. where it’s sold in a store, how seriously it’s taken by a critical venue — but how it’s made in the first place. The artist-critic Frank Santoro shows in a layout workbook how the particular proportions of a printed sheet affect the page’s ‘live’ area, determining the types of stories that might be told and how the artist tells them (Scott 2017). The influence of material form is true of books but less often thought of because in literary publishing it’s rare for authors to control factors like paper grade, binding and typesetting. What’s of interest to creative writing is the admission of factors from the extra-textual world, especially as that world exists at the time of a text’s production, which text-based authors rarely mention in a work’s final form, but which may be exploited to affect the meaning of a piece. In text, where a work is likely to be written by one person and typeset by someone else, a potential holdover from the fact of production — a medial limit — is time; I think of the experiment by the American journal McSweeney’s in inviting a range of contributors to write ‘twenty-minute stories’, which were framed as such for readers, the temporal constraint thereby becoming part of the work’s meaning (Daley 2003). It’s standard in comics for some of the meaning to come from the trace of the hand — making you feel close to the artist, reproducing a sense of the artist in space and time. How can creative writers replicate this experience in processed text, retaining effects of life that can be used to shape how writing is read?

11. Bernard

12. Liz

In considering the interlocution between text and image in comics, many scholars have, like Barthes, rested the vocabulary of their conclusion in subtractive words like ‘never, neither, nor’ and in sweeping phrases like ‘the universal picture, immanent in all language’ (Barthes), ‘the ineffable’ (see France Lemoine’s excellent article on the adaptation of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past into a graphic novel), and ‘the invisible sign’ (see Roy Bearden-White’s ‘Closing the Gap: Examining the Invisible Sign in Graphic Narratives’). What this language signifies, to me, is the reaffirmation of what I have always suspected about meaning-making: that one voice is not enough on its own, that meaning is to be found in the one facing another, and elsewhere from either.

In his article on the graphic adaptation of Paul Auster’s City of Glass, Paul Atkinson discusses the ‘upper limit’ of the implied authorial voice in literature, and how it can be ‘conceived as a container with no outside or the outermost boundary of enunciation’ (2010: 117). This limit, however, doesn’t exist in the same way in comics, because the visual whole of the page always functions as an ontological ground:

The image (panel, page) is always a plenitude and asserts itself before the examination of its detail. The voice in a novel, by comparison, is always, to some degree, an abstraction: a deictic sign that coordinates the text and, in the case of autobiography, one that is gradually filled with each enunciation. (Atkinson 2010: 118)

This ‘diffuse’ nature of voice and narration in comics means that dialogical meaning-making is an inherent part of the medium itself, and, as Atkinson notes, means comics lends itself to metafictional, form-conscious, modes of storytelling.

In Terrence Malick’s film Badlands, a text in which the character Holly’s quiet, poetic narration contrasts with scenes of cold violence, we find another example of multimodal interlocution in the below sequence:

CUT TO WIDE SHOT of HOLLY with gloves on carrying the fish through the garden in back of her house. She looks around warily, then throws it out among the melons.

HOLLY (v.o.)

The whole time, the only thing I did wrong was throwing out my fish when he got sick. Later I got a new one, but this incident kept on bothering me and I turned to Kit. […]

EXT. FEEDLOT

KIT steps on top of a dead cow, as though to convince himself that it is dead.

HOLLY (v.o.)

For instance, he faked his signature whenever he used it, to keep other people from forging important papers with his name ...

The image of Kit standing on top of the dead cow in the feedlot remains on screen during Holly’s voiceover description of the way he faked his signature. What sense are we to make of the sick catfish in the melons, Kit’s boots on the dead cow’s flank, and a series of faked signatures? We might read here a sense of profound unease with one’s identity, a distrust of the world of signs, a sense that our actions might belie our idea of ourselves. None of these phrases grasp with the same precision, and the same lack of articulation, the juxtaposition of the cow and the signatures. Meaning in interlocution, wherever it occurs, speaks to lack — the ineffable, the invisible, the universal, however it might be phrased. Meaning in interlocution speaks to what cannot be said in one way.

Those five minutes in class when we saw the dishes being done and heard about a deflating blow-up castle have lingered in my imagination. I think it’s because I cannot say with confidence what it meant.

13. Ronnie

The value for me in teaching comics to creative writers — in other words, sharing space with a community of practice in a studio, lab and workshop — is that it opens questions also present in textual forms, but which feel somehow buried when I’m reading them and even when I’m working in them. Perhaps this is because the forms are older (at least as established practices), and therefore I answer formal questions through a practiced set of options. But perhaps too it’s because the discourse around comics is newer, more provisional. There’s a greater percentage of artist-scholars. Ways of making and ways of discussing are adapted from other disciplines, including creative writing but also visual art and film. Comics in its present form is newer than the novel, and certainly its reception in the academy and its place in creative writing programs is recent. Rather than teaching how to do, it invites practitioners to ask themselves again and again what a comic should be — abstract, narrative, expressive, formally perfect, long, short? Why this, and not the other thing? When a work is successful — meaning when, as in prose, it’s fulfilled what it’s set out to do — both the terms of intention and the way they resolve are likely to be peculiar, somewhere on the spectrum between surprising and shocking. Through using the same equipment as creative writing — voice, text, metaphor, structure, sequence, narrative, character, plot, tension, atmosphere, style — they provide different ways of using the familiar, and perhaps show that the equipment is always changed through use.

14. Bernard

Atkinson, P 2010 ‘The graphic novel as metafiction’, Studies in Comics 1.1: 107-25

Barthes, R 1985 ‘I Hear and I Obey …’, in M Blonsky (ed), On Signs, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 54-55

Bearden-White, R 2009 ‘Closing the Gap: Examining the Invisible Sign in Graphic Narratives’, International Journal of Comic Art 11.1: 347-62

Daley, D 2003 ‘An Introduction to Twenty-Minute Stories’, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, 3 December, at https://www.mcsweeneys.net/articles/an-introduction-to-twenty-minute-stories (accessed 6 December 2017)

Eisner W 1985 Comics & Sequential Art, Tamarac, FL: Poorhouse Press

Lemoine, F 2015 ‘The Representation of the Ineffable: Proust in Images’, in C Clüver, M Engelberts and V Plesch (eds). The Imaginary: Word and Image, Leiden: Brill, 131-46

Malick, T 1973 Badlands, United States: Warner Brothers

Miodrag, H 2013 Comics and Language: Reimagining critical discourse on the form, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi

Molotiu, A 2011 ‘Abstract Form: Sequential Dynamism and Iconostasis in Abstract Comics and Steve Ditko's Amazing Spider-Man’, in M J Smith and R Duncan (eds), Critical Approaches to Comics: Theories and Methods. London: Routledge, 84-100

Plimpton, G 1986 ‘EL Doctorow, The Art of Fiction No 94’, The Paris Review 101 (Winter), at https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/2718/e-l-doctorow-the-art-of-fiction-no-94-e-l-doctorow (accessed 6 December 2017)

Saraceni, M 2003 The Language of Comics, London: Routledge

Satrapi, M 2003 Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood, New York: Pantheon Books

Scott, R 2017 ‘Material form as a structural force in Nicki Greenberg’s The Great Gatsby and Hamlet’, Media International Australia 164.1: 139-50

Speigelman, A 1991 Maus, New York: Pantheon Books

Stevens, W 1997 ‘Not Ideas About the Thing But the Thing Itself’, in F Kermode and J Richardson (eds) Collected Poetry and Prose, New York: The Library of America, 451–52

Ware, C 2006 ‘Thrilling Adventure Stories’ in I Brunetti (ed), An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons and True Stories Volume 1, New Haven/London: Yale University Press