Martu filmmaker and artist Curtis Taylor talks with Lisa Stefanoff about his work in the production and international promotion of Lynette Wallworth’s Virtual Reality Film Collisions, a project that tells the story of his grandfather Nyarri Nyarri Morgan’s experience of the British atomic bomb tests at Maralinga and ongoing care for his country. Curtis reflects on the value of different art and media forms for conveying Martu stories, enduring traditional knowledge and contemporary concerns, and discusses his own cinematic reflections on the powers, risks and roles of new media in Martu communities.

Keywords: Martu — Indigenous — Australia — screen — technology — art — Virtual Reality

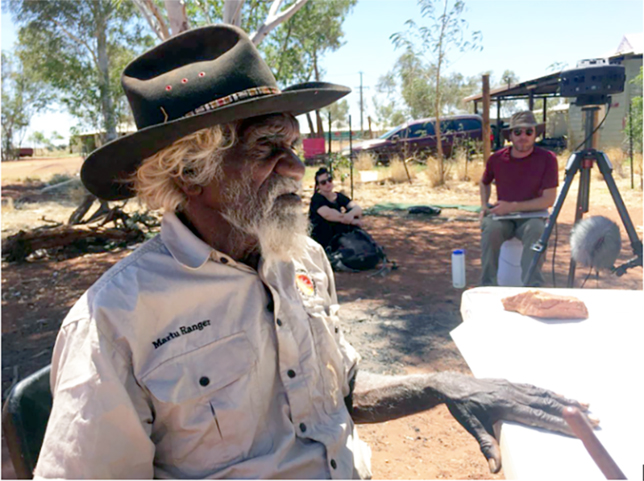

In late 2017, with this edition of Axon in mind, I recorded a conversation with Warnman filmmaker/artist Curtis Taylor about his roles in the production and promotion of the 2015 Emmy award-winning Virtual Reality film Collisions by Australian filmmaker/video artist Lynette Wallworth.1

Curtis was Director’s Attachment, camera assistant, cultural liaison, and one of the narrators of Collisions. His grandfather, Nyarri Nyarri Morgan, is its central character. Curtis’ cultural liaison work was crucial to the creation of the film, and entailed multiple kinds of mediation. Not only translating back and forth between director and storyteller, and literally between Martu Wangka and English languages, but also working with the multi-lens cameras during the shoot, and on sound in post-production, Curtis was closely involved in melding his and Nyarri’s knowledges and senses of country with the prosthetic sensory capacities of the VR technologies used in the project.

In this edited version of our conversation, Curtis’ commentary sheds light on Collisions as a new kind of collaboratively crafted western desert revelation, materialising his grandfather’s story, voice and country in visible/audible and invisible/silent ways, depending on who is wearing the headset. Curtis and I have worked together on and off since 2011 to bring his films, art and ideas to new audiences through screenings and talks staged in ‘remote’ and urban places in Australia and also overseas.2 The impacts and implications of new media technologies for storytellers grounded in strong traditional desert Law/Lore and Culture are topics that have always connected and engaged us. As we talked about the dynamics of cultural liaison, translation and mediation at play in Collisions, Curtis shared a striking explanation of western desert people’s lived experience of country as a kind of dynamic ‘360 spatiality’ that encompasses not only the visible and audible landscape, but also changes in the world, storied history and interpretation of country, and story itself — all of which are, as he also explained, immanent in desert paintings.3 These elaborations allow us to think about Collisions as a project continuous with this distinctive performativity of painting; a bold collaborative experiment that attempts to conjure a Martu/Western Desert way of being ‘spatial’ in the world as lived sensory experience, knowledge and history, inflected through the phenomenology of ‘immersive’ Virtual Reality audio-visuality.

Our discussion began with my asking Curtis to explain the Collisions project and his involvement in it.

Curtis Taylor: The Collisions Virtual Reality project was a collaboration between Lynette Wallworth and Nyarri Morgan. It’s an oral history of Nyarri’s first encounter with the western world, in the 1950s in South Australia. He encountered this mushroom cloud in the distance that he didn’t have a word for, and later learned that people were calling it the after-effects of an atomic bomb. He learned that at the Warburton mission. He and two other fellas were walking across the tri-state border — WA, Northern Territory and South Australia – walking back towards Warburton. That’s where he learned what that name was: a ‘bomb’. Collisions is a story about how we can further look after the country for the future generations and learn from people who have gone before us, and how they looked after the land, their homeland. Some of the underlying stories are about exploiting minerals, mainly uranium in this case, from Indigenous people’s land.

This project is all in Virtual Reality. It’s a massive experience that you get to immerse yourselves in with the protagonist, Nyarri. It’s narrated by Lynette Wallworth and me. It was shot over a week in Parnngurr — Cotton Creek, Western Australia — in the Karlamilyi National Park, East Pilbara region. We shot it there because Nyarri lives there today, at Parnngurr. [It would be] a lot to retrace his steps back to the Maralinga area to retell his story. We used the land around East Pilbara where he lives today so it was easy for him and for us to shoot around where things were accessible to us that we could shoot.

It was really great for us, and for me, to be part of this project, my first VR project. I was Director’s Attachment to Lynette Wallworth. I learned a lot in collaboration between different artists and tech people that we had on the crew; from the guys at Jaunt VR — Patrick and Kelly from the [United] States — and Lynette. [I was] translating the directions that Lynette was going for, to Nyarri. Giving directions of action and dialogue for the shoot on the day. I did other projects with other filmmakers and other artists that are using more traditional film, shooting in and around the Parngurr or Karlamilyi area, and I know where to and where not to shoot. In this case, it was 360 shooting; capturing everything. It was really great to be in the perspective of the camera even before shooting it, [knowing] where to place the camera and what it could and could not capture around the country. People want that [the camera] to be hidden or not in the view when they’re experiencing virtual realities.

It was a really great experience to work alongside all these artists, and Nyarri and Nola,6 from when we were shooting at the beginning to post-production. I travelled to the States to lay down some narration and sounds at Skywalker Sound.7 To work with Tom Myers — somebody who has been around in the industry, a really well-respected person — just to have been in that place and experience that kind of environment, the studio! ... That place is amazing with all the equipment and the technology and all the gear. It’s just incredible. To have Tom Myers there and going through the shots and the sounds and talking about how and what should be recorded, the intent for us when we’re showing it [the VR film] and how people react to different sounds. Learning about that side of sound is really extraordinary. It was a really great experience to work alongside these collaborators. And the guys at Jaunt VR, they’re not traditional filmmakers, they’re more tech gurus. It was really good to see where different people are at, in their different disciplines.

It’s not a traditional directing film, because it’s not on a flat screen, where we [visually] direct a viewer’s attention towards a certain place in the movie that we want them to see. It was [done] more with sounds. Sound played a huge role in creating another element. We directed the viewer when they were in the immersive experience. They could turn towards or could be directed by sound to certain places in the movie that we wanted them to see, in a certain direction, in the experience. I didn’t understand it at first, but I did later on when I got to experience the sound and the images all together. I was really happy with the sound that I put down in the dialogue, translation-wise.

Lisa Stefanoff: At the start of the project, how did you explain this new medium to Nyarri?

Curtis: We didn’t really. We tried to explain this new meaning of Virtual Reality to Nyarri, but he immediately got it when he saw the camera. He said, ‘This camera is a ball’, so we put the camera in front of him and he said, ‘This camera has 16 eyes, 16 cameras, so I know where to place it in the country that I want the viewers to see’. Martu have that spatial knowledge of country, of how they view their land. It didn’t take long for him to realise this medium. A lot of Martu and Western Desert people paint in that way anyway. Their country in spatial, expansive space-time.

Lisa: I think I know what you mean, but a painting is two-dimensional and …

Curtis: Painting isn’t two-dimensional. It’s a spatial universe, so a lot of people see in 360. That’s how they paint, from underground subterranean to right up to the sky. A lot of people have that knowledge anyway from walking around and having different knowledge at certain times of their life. How they put that down on canvas tells a lot. I think a lot of Western Desert artists really get that. They understand this is just not two-dimensional, or not linear. It’s a spatial environment where you see 360, and 360 again. For an example, you might start a painting at Karlamilyi, or somewhere in the desert like Jilakurru or somewhere, and [there’s] that story. And that’s where you might place a camera. But that story, they’re telling from underground right up to the sky and all around spatially. They’re including everything: from the plants, to the animals, to the oral histories of different people that traversed that part of their country, changes in the weather, changes in the environment, changes in the culture of different times in history, to right now, where they’re at, at the time when they’re putting down their contemporary take on that part of their country.

Lisa: When did you realise that this new medium was going to be almost a perfect fit for Martu, or Western Desert, senses of country, for this story about country?

Curtis: It was apparent straight away when Lynette was looking at different mediums to tell Nyarri’s story. It’s hard for audiences — with anybody’s story — to really experience it to the fullest. They need to be immersed in that environment and in that person’s life. It can only be done in this way, being transported for 17 minutes as a stranger. Somebody watching in Germany, being transported into the Maralinga area during the 1950s in Australia when all these events unfolded. This medium was the perfect fit for these really strong visceral stories from individuals who lived from pujiman (‘bush[man]’ times) right up to 2017, into this time in the world now, and the changes that happen all along their lifetime, which is really quite special. It only can be experienced in that way for other people to fully understand the timeline of Australian history from somebody born out in the desert, [who] lived nomadically, and [who] has these memories of encounters and collisions between Martu and Ngaanyatjara, to foreign people coming into their homelands. I think this medium was really fit for telling that and showing to audiences, and for them to really grasp it and really feel this. Really feel the time.

Lisa: VR offers new ways of seeing but it also changes our sense of what it is to see, to look, to listen in visual space, to be in relationship to a screen. Especially when being used for a documentary story, this kind of immersivity dissolves older cinematic senses of what a screen is by setting up new dynamics between a viewer, or ‘experiencer’, and the people in the film. Senses of intimacy can be played with and fabricated in new ways. I found the early scene in the film, when Nyarri and Nola are standing together in their yard ‘looking at’ me as the viewer who is being invited into the story, with your voice narrating, and you visible over by the far fence, very unsettling. I was immersed in a relatively close-up shot that conjures a realistic distance-size scale. The illusion in the direct address set-up of that scene is that we are all co-present and looking at each other, but of course our gazes aren’t meeting and can’t meet. I felt I was being asked to believe that we had that level of intimacy, albeit as strangers, as a starting point for experiencing the story. This put me into a strange kind of disembodiment, in tension with the medium working hard to re-embody my senses across this ‘uncanny valley’ (as it’s called in AI), but also making it completely clear that it is impossible for gazes to meet in the space of the film. What do you think about the illusions of intimacy conjured by VR?

Curtis: Yeah, the gaze, whether they meet or not … [In] an immersive experience, these ‘normal’ interactions that we have programmed to ‘meet’ each other’s gaze, it’s like a disruption in the program, that experience. But also, probably, if you think about it more you’ll come away with more worry and trouble — ‘I really want to experience this fully, but I really can’t because it’s not the real world’. [One] shouldn’t try to confuse that, or have at least that perception. We shouldn’t get confused about whether it’s normal. It will become normal. It already is, and it will be, to look at your phone more, to have a conversation with somebody [that way] rather than putting it down and walking up to somebody, a complete stranger, and saying ‘My name is blah, blah, blah and what are you doing today?’

Lisa: The premise of Collisions, that the nuclear story is a shared story we’re all a part of, is really important. I just felt anxious that the medium was anchoring this claim through the illusion of co-present reciprocal gazes; that I was being asked to feel an ethics of connection and responsibility as a reflex of this ‘social’ mode of immersion in the medium itself.

Curtis: I guess with these illusions that we’re playing with, you just got to be really careful, not get mixed up or confused with the real and the virtual world. We can get really lost as an individual, as a person, in whatever persona that you make. We don’t want to eventually lose ourselves and become an avatar, sort of thing.

Lisa: The statement you made in the Canning Stock Route project in 2010, that Aboriginal people are now ‘dreaming with a new technology’, has been widely quoted. Your own film work also tells cautionary stories about the dangers and risks of new technologies for people who live according to traditional Law and culture. Mamu (2011), for example, told a story about the repercussions of misusing social media to share cultural secrets, and also made comments about alcohol as a potentially malign force in people’s lives. A few years ago you told me that you depicted the frightening figure of the Martu mamu monster in that story as a gatekeeper for what should and shouldn’t be posted and shared online, ‘a warning to Aboriginal youth today’.9 The film builds dramatically to a horror climax set at a popular community drinking spot, with the mamu using its powers as a violent punishing assassin, killing the young man who has transgressed the Law on Facebook and ended up drinking in isolation, haunted by his actions and fearing his fate. In contrast, as you’ve told me in the past, you always observe relevant protocols in your own uses of social media, follow regional protocols in projects you’re involved in in other people’s country and you always check the ideas and content of your own films and art with your elders. ‘Keeping it Martu’, as you say, makes that a straightforward process. New kinds of social media that cross space and time boundaries, as well as technologies like VR, are becoming more accessible to everyone everywhere at an accelerating rate. What are your thoughts about the presence and life and powers of new kinds of media and devices that people can access in the Western Desert today?

Curtis: In our Western Desert history, it’s still very recent that there’s a lot of collision and clash between different technologies, old and new ones that are introduced. I think individuals have been constantly trying to find a way that they could utilise them to the best of their ability, especially in terms of recording oral histories of people. It’s great that those stories can be heard and can be formatted into different files or different players, that you can play in your phones. Back then it was a cassette tape, then CDs, and [now] it’s more contemporary ones – audio recorders uploaded to the internet. Accessible to everyone? Or you choose who it should be heard by. I still have that kind of thinking when I make work about new technologies. In the case of making Mamu, I also had that warning that we can utilise this to benefit ourselves or use it to destroy ourselves, unwillingly or, sometimes, willingly. By ‘destroy’ I mean ruin the reputation of individuals or a story that they have. It can be very strong, what’s recorded. The fragility of it is when that trust is broken or misused and it’s used in a destructive kind of intent. I always think about that. That’s what I was thinking about when I was writing Mamu back then. I was thinking about that story. I never really got into all those old applications10 that came out before Facebook and Twitter. Living in a remote area in the desert, I wasn’t exposed to that, but I could see there was a history of caution that a lot of older people talked about, that they had experienced before; that the information that they gave shouldn’t be in a certain public domain. Those are kinds of things that I’ve been thinking about for a long time. I kind of attack that [problem] when I’m making new work, and am always being vigilant in those ways.

Lisa: Does cultural lore always have a way to engage with these new technologies and their challenges, or is it running to keep up with them?

Curtis: I don’t know if it should keep up or if it needs to keep up. I think the question is: ‘who’s being intrusive here?’ Is it the lore, is it the culture, or is it this new technology? On the cultural sides, there’s always stories about different ancestral heroes for different songlines that have been taught, that have been sung. Those ancestral heroes who feature in those stories carry with them something foreign, something that has some kind of magic or power or some kind of aura around whatever they possess, or around them themselves. Always it keeps teaching us about new things that are coming into our lives, and how we choose to use them: sometimes cautioning us, but also giving meaning to whatever their intent was. Using that technology for good or bad, or to manipulate the season or the environment in the land around them, where they were, where they traversed through that time. Whether it was to manipulate seeds to make them grow really quick to feed themselves while they were on their journey, or whether they made the land barren to kill off people or animals, to teach them a lesson. In that way, in these new technologies, there’s always those elements to our old stories that we can learn from. I think that when we look at how these new technologies are being used every day, we can take some kind of teaching from them [the old stories]. Lessons. Everything’s already been done before. Nothing is original anymore, but I guess it’s how people manipulate different things. Like, if you’re using these phones to track somebody or to get back at somebody, that’s already been done in our old stories. Different ancestral heroes have been doing that in search of food or in search of a mate or in search of more power. ‘Who’s being intrusive?’ again comes back to that. For me anyway, it’s ‘should the lore dig into that more, or has it taught us enough, gave us lessons that we should really listen to and learn from? Should we keep indulging in these foreign or new technologies that will eventually become monotonous and we’ll be looking for something else to fill our desire, whatever that is?’ It’s a really hard one. I don’t know.

We change, and every day when we grow older we speak in different ways. As you learn the true meanings of things, when you’re expressing yourselves, you learn how to not waste words any more. Maybe we’re wasting too much of that, with not interacting face-to-face, having interactions with other people where it’s just more in this virtual realm. Maybe we should go back to looking up more, looking people in their faces, turning your phone off or leaving your phone at home, or maybe not having a phone any more? Not having a device.

Lisa: Some of the first places you showed Collisions, other than to the people in it and to their community, weren’t in Australia. You took it pretty quickly to Sundance and then the World Economic Forum …

Curtis: It opened to the World Economic Forum in Switzerland (Davos, 2016). That audience there was mainly change-makers in the world and heads of state and people with a lot of influence in changing the course of history in their country and globally too. For us to take it to that kind of forum and to immediately show it to those audiences there … — most of them, they really got it straight from the get-go. They said ‘My country, where I come from, has a nuclear history’, and [they talked about] how they are dealing with it. Heads of state from Asia, Europe, Australia. From all over the world, people came and saw it. It immediately struck a chord with different individuals in different ways. They had relatives or friends who have had experiences in their life with atomic testing or nuclear disasters, or even worked on those kinds of projects. They immediately got the message, and the message was different to different individuals. More people were concerned about how they’re going to look after their environment into the future and how they’re going to preserve it globally, or regionally first in their own country and globally for the rest of the world. A lot of people took different messages from different parts of that story and were really interested about the future of Martu, or Nyarri and his people, how they’re looking to the future and how they’re working towards preserving their land for their children. It was really an eye-opener. And for us, to take it to Switzerland at the World Economic Forum where those audiences are change-makers in their part of the world and globally. They’re going to effect change for their people and for the rest of the world. It was really thought-provoking for everyone. From then, we took it to Sundance in Utah, not far from ‘4 Corners’ in the deserts of New Mexico, where they did some of the first tests of nuclear weapons. Atomic testings have gone on in America. It was really special for us to take it there, for me to take it there, to travel on this journey with Nyarri and Nola. I can’t really speak for other people’s experience and how they felt. There was a lot of really awesome, really thought-provoking feedback that came out of people experiencing Collisions.

The one [memory] that really strikes a chord with me is when Lynette showed it to a famous painter from Kazakhstan. He was born without arms. When he saw Collisions in this Virtual Reality, he remembered the time when his mum and dad, before he was born, while he was still in the womb, used to go and see atomic testing in the deserts in Kazakhstan, done by the Russians. It was seen as a form of entertainment back then. When he was born, he was born without any arms. He could see that that was his story too, the nuclear story. That just struck a chord with me. I still tell that story whenever people ask me about Collisions and [ask] what was the most profound experience that I had on this journey, or that I saw that other people had.

It was awesome to travel with this project around the world and to translate it into different languages, like when we took it to China, to Tianjin, for the second World Economic Forum; ‘the Summit’ they call it. It was translated into Mandarin. It was great to have a majority of Mandarin speakers coming back and saying ‘Oh man, I really love it and it made me think about it a lot.’ I guess for some viewers it’s maybe also too much emotion, coming from listening to this story and being immersed in this story, experiencing it.

Lisa: When we presented Collisions at a conference in Sydney I observed people being very emotionally moved one way or another when the experience ended, and most needed to sit quietly for a while after. Some people cried. Others were very still and silent. People are given entree into a very emotional story on the level of the individual, of Nyarri, and at the same time to the national, international narrative. The whole sorry story. They’ve also been taken to a place — Nyarri’s country — where they’ve probably never been and may never go or may have dreamt of going, and they have to wake up back into the room they’re sitting in, on a chair in a university, or wherever. They have only met Nyarri as a character, despite the illusion of encounter. Was it important, when you took the film to Davos, that people could meet Nyarri personally as well?

Curtis: Yeah definitely. That’s what we most definitely did, in Davos and in Sundance. That Nyarri be present there, that after people experience Collisions in the virtual world, virtual reality, they have this more human interaction with the person whose story it is. That they don’t have just an emotional feeling after they’ve come out. They want to engage more. Not just with the experience itself but with that human interaction with whatever they’re experiencing in virtual reality, or in any virtual space. I think it’s really important to have that element there. You can make that work. Sometimes you can’t make that work for a lot of different reasons — whether that person is still alive or able to travel.

Lisa: Did Nyarri know from the beginning of the project that he would have that opportunity to accompany it, and that that would be an important part of the presentation of the film?

Curtis: Yeah, that was the most important thing. He really wanted to travel with his work. It was imperative for him to be there to talk with these leaders, to talk with these change-makers. He really wanted to, for a long time. He’d been talking about it and he’s been longing for this. He’s been always talking around the campfire with his family that he has this really special story, this message that he needs to get out there into the world and to teach and to deliver and share with the world, and share with different individuals. Maybe they had similar experiences, or entirely different from Nyarri, as a person. That’s the important thing that he really wanted to do. I know he talked about it a lot, that he really wanted to travel with the work and make sure that people understand and really get the message and engage with him on different levels.

Lisa: Your role as a connector between Lynette as Director and Collisions’ major audiences seems to have been essential.

Curtis: Yeah. Me and Nola were more like a conduit in making sure Nyarri’s message was translated truthfully, so that we as a whole group make sure that Nyarri has the best experience that he has on the road with this work. And that’s what we really did. I was making sure — when we went to Switzerland, when we went to America — that he is there, and making sure that he understands or making sure that other people understand that for us, when we show Collisions [it’s important that] he engages with the audience that he’s showing his work to. I can only speak on behalf of what Nyarri has already shared with me. I can’t speak for the man himself.

I had fun working on Collisions, and it was really great to be able to be on this journey with Nyarri and Lynette and Nola and the whole team, up to where we are now today. It is the first Australian Virtual Reality co-partnership [with] the US. The collaboration took out an Emmy.12 That’s really exciting, and one that we’ll talk about for a long time in the Pilbara, and in the Ngaanyatjara lands. For this Maralinga story that involves so many different people from different walks of life — from the day they tested the bombs to now, and all those events that unfolded from then. For a lot of Australians, it’s to learn that history, their own history about atomic testing and weapons and nuclear issues, but also be immersed in this time and this place, seeing it, experiencing it through a Martu or Ngaanyatjara or Anangu Pitjantjatjara lens. I want to say ‘Thank you Lynette for having me on board, and thank you Jamu [Grandfather] Nyarri and Nanna Nola for [my] being part of your story’.

Lisa: You’ve just become a father, congratulations. When you look into the world that your son’s coming into now and where he’s headed, do you think about what new technologies will one day be surrounding him?

Curtis: I don’t really think about it that much. What I’d like to foresee, for him and for my relationship with my little boy, is to teach him to become bilingual. Learn other languages. Learn other Indigenous languages, but learn also my language from my family so that there’s always this continuation of Western Desertness, Warnman, through his life. That’s what I would like my relationship to be with him in the future. Whether for his own experience with the virtual or digital world, his own relationship with that, or whether he is with his friends or with his parents, with his family. I’d like to teach him more language and also make him bilingual so he is fluent in picking up different sounds and pronouncing sounds and knowing how the structure of different languages work. That’s the most important thing that I really want to have with my son. Yeah, languages.

Notes:

1. See http://www.collisionsvr.com.

Collisions is available online at https://www.jauntvr.com/title/2981572c5e. The Jaunt app is free and available for multiple VR viewing platforms at https://www.jauntxr.com/apps/. For additional information, ‘making of’ footage and a discussion of the project featuring Lynette Wallworth, Nyarri Nyarri Morgan, Nola Taylor and Curtis Taylor, see https://www.acmi.net.au/events/collisions-lynette-wallworth/

2. See Yarljyirrpa (Clever People), a video published in the special ‘Same but Different’ edition of Cultural Studies Review 21.1 (March 2015),

https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/article/view/4436/4770

3. To learn more about Martu paintings, see http://www.martumili.com.au.

4. Image available at

http://www.collisionsvr.com/assets/downloads/PressNotes_Collisions_WEFDavos_SundanceParkCity_012216.pdf

5. Image available at

http://www.collisionsvr.com/assets/downloads/PressNotes_Collisions_WEFDavos_SundanceParkCity_012216.pdf

6. Nola Taylor, Curtis’ grandmother.

7. Skywalker Sound is part of George Lucas’ Skywalker Ranch film production ‘campus’ in California. See https://www.skysound.com.

8. Image available at

http://www.collisionsvr.com/assets/downloads/PressNotes_Collisions_WEFDavos_SundanceParkCity_012216.pdf

9. 2013, Lisa Stefanoff interview with Curtis Taylor, unpublished.

10. MySpace and other kinds of chat rooms, for example.

11. Image available at

http://www.collisionsvr.com/assets/leadership/Collisions_PLM_Production-1116HR.JPG

12. The film was awarded a 2017 Emmy for Outstanding New Approaches to Documentary.