Found poetry borrows from other writers – from different writings, artefacts, and sources – always attributing and referencing accurately. In this paper, regional daily newspapers and their front page headlines are privileged as primary texts, the Found Poetry performing as nonfiction lyrical collage, with applied rules, nestling beside them.

Considering the notion that contemporary poetry ‘inhabits language’, this paper uses three forms of Found Poetry – erasure, free-form and research – to test and demonstrate both literally and metaphorically, its veracity. Implicitly nonfiction, these poems create a nuanced and rhythmic lineated transcript of Australian life, derived from regional legacy newspapers, while they endure. Furthermore, using a comparative textual method, the aesthetics of Found Poetry is established visually.

This paper is the second in a series derived from the beginnings of a research project into Australian legacy newspaper stories and Found Poetry. The first was a sequence of prose poems; this second collection is lineated and contributes to the notion of poetry mediating and enriching our understanding of the reality of the everyday.

Keywords: Found Poetry – Australian outback – lyrical collage – legacy newspapers – lineation

Introduction

There are many definitions of Found Poetry, understandably echoing each other. My definition is simply: Found Poetry is lyrical textual collage, with rules. The rules create a writing to constraint paradigm, which is as evocative as it is challenging. My research into this area is relatively new but there is one notion I am certain of from these early forays – poetry is as ubiquitous as language: our earliest sense of sound, in most countries globally, is lyrical or poetic, in culturally differentiated lullaby and song, hummed or whispered into our ears, if we are fortunate enough, by our mothers/parents/family. As Dunning and Stafford wrote 25 years ago, poetry inhabits and dwells in ordinary language:

Plenty of strong and beautiful poems are made from plain language. You sometimes hear such language in conversation, when people are talking their best … You can find moving, rich language in hooks, on walls, even in junk mail … So, poems hide in things you and others say and write. They lie buried in places where language isn’t so self-conscious as ‘real poetry’ often is. (Dunning and Stafford 1992: 3)

They go on to describe the method behind Found Poetry: ‘… you don’t start from scratch. All you have to do is find some good language and “improve” it’ (Dunning and Stafford 1992: 3), citing the main aim ‘is to discover and present in an artistic and attractive way connections in the language’ (13). It is these ‘connections in language’, experimenting with form, that intrigues me. As Frazier writes: ‘… the Found poem work with all the poetic elements of a quality piece of writing – organization, audience, line, image, sound and surprise’ (Frazier 2003: 67).

This paper is the second in a series of papers I hope to produce from the beginnings of a research project into Australian legacy newspaper stories and Found Poetry. The rationale behind the bigger project – ethnographic in texture at its edges – sets out to create lineated poetic renditions of regional news of the day, circumnavigating the continent. As Lester writes: ‘By taking news articles and arranging them as poems, what was mere news in one context becomes the human experience it really is’ (Lester in Gorrell 1989: 33). My aim is to produce a cadenced and lyrical nonfiction transcript of Australian life, inspired by and appropriated from regional legacy media, while it still exists (Joseph 2017). My constraints are front page stories and headlines, and where they slip over onto other pages of the newspaper. No other text is used. My hope is to create new texts substantiating what Burdick writes:

Poetry as a form is not only a different way of writing, it is a different way of presenting and viewing the world: metaphorically, symbolically and in a condensed form. These effects allow a stronger impressionistic meaning for the reader or listener. (Burdick 2011: 4)

Lahman and Richard concur: ‘The ability to resonate with readers and expose them to a new experience is fundamental to poetry’ (Lahman and Richard 2014: 344). Many writers have created their own definitional tag and rationale for Found Poetry: author and poet Annie Dillard calls it: ‘… editing at its extreme; writing without composing’ (Dillard 1995: x); Prendergast writes it is: ‘the imaginative appropriation and reconstruction of already existing texts’ (Prendergast 2006: 369); Burdick says a Found Poem is: ‘created by selecting words and phrases from an original text, then re-arranging these words to create a poem that represents the meaning of the original text anew’ (Burdick 2011: 3); and Dangerfield Lewis explains it as:

… a form of poetry that is produced by extracting words and phrases from another written source. The words and phrases taken randomly from other sources (such as newspaper headlines, novels, street signs, text books, etc.) are then rearranged in a manner that gives the words new form and provides clearer meaning and interpretation. (2012)

Synthesising all these definitions, it is clear that practitioners are looking for methods to mediate texts, and engage audiences effortlessly in a deeper dialogue about meaning. As Patrick writes:

When writing the actual poem out of selected phrases, I found a new meaning or a new dimension to the text I already loved. I was able to take on a new perspective and look at the same text from another angle. (Patrick 2016: 389)

Accordingly, this form lends itself effectively to a second rendering of news of the day, hopefully delineating subtle meaning and nuance in everyday life events – some dramatic, some ordinary, some celebratory – but all gate-kept and reproduced by newspapers as a cumulative regional daily accounting.

The beginning of this research was a recce journey to the centre of Australia in 2016. The first paper[i] contains six poems, five of which are nonfiction prose poems, experimenting with the four most commonly used Found Poetry practices.[ii]

This second paper includes three more poems, lineated this time, and using two of the most commonly used methods – erasure and free-form excerpting and remixing – but also includes another method of Found Poetry known as Research Found Poetry (Patrick 2016: 386). I include this method as the literature around it is polemical – at once lauded by practitioners and at the same time, diminished by detractors.

Found Poetry history

If Found Poetry[iii] has a rather lengthy genesis. The most cogent and comprehensive rendering of its history I have discovered in the literature around Found Poetry is in Lisa Patrick’s 2013 thesis entitled ‘Found Poetry: A tool for supporting novice poets and fostering transactional relationships between prospective teachers and Young Adult literature’. Robson and Stockwell write that Found Poetry was:

Invented by the Dadaists and developed by the Surrealists in the 1920s as a means of removing the authority of the author, found poetry became popular as a democratising statement in the 1960s and is now much used in second language teaching. (2005: 93)

But Patrick claims it ‘has its roots in an ancient form of poetry known as the cento … The cento leans heavily on the tradition of found poetry; lines from other poems are used to craft a new poem’ (Patrick 2013). She cites work from the fourth century but quickly leaps to the 19th century, then into the 20th and 21st centuries. She writes that the first book of Found Poetry published in English was A stone, a leaf, a door (1945) by John S Barnes and claims: ‘Although found poetry’s origins can be traced back to the fourth-century cento, the art form did not truly take root until the early 1900s’ (Patrick 2013). She then writes of the burgeoning of Found Poetry throughout the 1960s, citing Harry Gilroy in a New York Times article:

The game these days, for some poets and a lot of other people who like to play with words, is found poetry. It is not exactly new, for examples are scattered through past literature, but it is catching on and everything in the contemporary flow of print is providing more material than ever …. (Gilroy 1967: 34)

Patrick lists the many and varied texts and authors who have produced Found Poetry, including Austin Kleon’s Newspaper Blackout (2010). He writes in his Preface: ‘What’s exciting about the poems is that by destroying writing you can create new writing’ (2010: xv’; emphasis original). In Kleon’s Introduction, he claims there is a 250-year-old history of what I am attempting – poetry from newspapers (2010: xviii). Here, he cites instances and their authors of poetry found and created from newspaper text, although he writes: ‘Admittedly, this idiosyncratic history looks less like a straight line and more like blips on a radar screen’ (2010: xxii).

It is good to know there is a canon of poems derived from newspapers, even if Kleon believes his history is a little sketchy. His process emphasises the fun in the enterprise. I wrote in my first paper on Found Poetry that like Prendergast, I have been ‘caught’ by this endeavour (Prendergast 2015: 682) and ‘this creative practice has astounded and delighted me’ (Joseph 2017). I reiterate those notions here. And again, mapping my work to Prendergast’s research where she cites elements that take her attention: ‘aesthetic power; imagery, metaphor; capturing a moment; truth-telling, bravery, vulnerability; critical insight, often through empathy; surprise and the unexpected’ (Prendergast 2015: 683), the Morrison article below attracted me because of its aesthetic power; the second poem because of its surprise and the unexpected; and the third by Andrea Johnston because of the truth-telling and vulnerability of the subject.

Methodology

The return trip to Central Australia took exactly three weeks, leaving on 4 July 2016 and returning on 25 July. We headed from Sydney towards Port Augusta and straight up the Stuart Highway, through South Australia and into the Northern Territory, turning left at Erlunda for Uluru and Kata Tjuta, arriving on 11 July. En route, we camped in regional centres: Renmark, Woomera, Kulgera (two nights), and then onto Uluru and Kata Tjuta (two nights). After that, Alice Springs (two nights); then onto the East MacDonnell Range and then the West MacDonnells, before beginning the long drive home, via Tennant Creek, Lightning Ridge, and Mudgee. My main aim was to collect as many local and regional newspapers in these centres, both free and paid for. Some I found in smaller townships between the larger centres, mainly at roadhouses. The objective was to translate from the news story format to a piece of prose or lineated poetry in a bid to map the journey, capturing parts of the outback with meter and lyricism through Found Poetry. If successful on this reconnoitre, then the fully realised research project, circumnavigating the continent, was feasible (Joseph 2017). Eighteen local or regional newspapers were collected en route. For the purpose of this paper, I have selected three front page stories, all from the Northern Territory, to apply three different types of Found Poetry.

Found Poetry methods

As mentioned above, there are four main common Found Poetry methods. They are:

- Erasure: Poets take an existing source and erase the majority of the text, leaving behind select words and phrases that, when read in order, compose the poem;

- Free-form excerpting and remixing: Poets excerpt words and phrases from their source text(s) and rearrange them in any manner they choose;

- Cento: Poets unite lines from other authors’ writings into a new poem. The original lines remain intact; the main intervention comes in arrangement and form; and

- Cut-up: Poets physically cut or tear up a text into words and phrases, then create a poem by rearranging those strips. Arrangement is intentional or haphazard (Joseph 2017).

For this paper, I am using Erasure,[iv] and Free Form Excerpting and Remixing Poems,[v] as defined above. I am adding to this list and using here, a fifth type – Research Found Poetry, a form growing particularly in the qualitative data gathering sphere. Patrick writes of this form of Found Poetry: ‘In general terms, research poetry is written from and about research subjects and data. Research poets use the art of poetry to explore and explicate the lived experiences of their study participants’ (Patrick 2016: 386). Prendergast also calls this type of writing ‘poetic inquiry’. She writes:

Poetic inquiry is an area of growing interest to arts-based qualitative researchers. This is a fairly recent phenomena in qualitative inquiry … There are examples of poetic inquiry to be found in many areas of the social sciences: psychology, sociology, anthropology, nursing, social work, geography, women’s/feminist studies and education are all fields that have published poetic representations of data. (Prendergast 2009: xxi)

Found Poetry is just one form of what Prendergast tags ‘poetic inquiry’. Patrick’s own understanding of Found Poetry is: ‘… a poetic form created by reframing words from the linguistic environment surrounding the poet’ (Patrick 2013). But her framing of the rationale behind Research Found Poetry concurs with what Butler-Kisber writes more generally about melding the arts with other humanities’ modes of investigation: ‘The rationale for including arts-based representation in qualitative research is that form mediates understanding’ (Butler-Kisber 2002: 232). This goes to the heart of Found Poetry: mediating a text to create deeper, or even new, more nuanced meaning. If Butler-Kisber’s claim that the form of a thing mediates its meaning is correct, then when completed, my collection of poems ‘will hold in place the temporal space of the regions and towns we travel to and through, creating a mimetic yet lyrically variant rendition of the news of the day’. Creating a new way of seeing (Joseph 2017). As Dillard writes: ‘… by entering a found text as a poem, the poet doubles its context. The original meaning remains intact, but now it swings between two poles’ (Dillard 1995: ix). This doubling or creating another, or deeper, meaning or reading of a published text is what interests me (Joseph 2017).

Research Found Poetry is intriguing, creating a collaborative space between researcher and subjects; perhaps a ficto-critical space. Transcripts are made of interviews, the researcher then, through analysis and thematic rendering, looks for patterns in responses, pulling out words and phrases resonating across her subjects. This then is reformatted lyrically or as Dow writes: ‘reconciling the language of information with the language of art through … poetic profiling’ (Dow 2016: 116). But as a method of interpreting data, it is still in its infancy in terms of acceptance. As one researcher writes:

Perhaps what I share here is not really poetry, but I know it is the essence of the data, the story the data were telling, that became clearer and clearer through my process of choosing some words and eliminating others (Wiggins 2011: 7).

It is this engagement with the language – the selection and exclusion decisions; reducing another text to a lyrical form, perhaps gleaning deeper meaning – that is my ambition with the three poems in this paper. Dangerfield Lewis explains that ‘found poetry also allows for personal interpretation and calls on the found poet to identify key passages and terms in text which illuminate the original authors meaning and intent (Dangerfield Lewis 2012). And Gorrell writes that a Found Poet must be ‘a seeker, discovering hidden poetic potential in non-literary, expository prose’ (Gorrell 1989: 33). I enjoy the parallel metaphor – my recce trip and future longer trip – is just that; seeking and experimenting with texts and the words that make them, while on the road.

Gorrell also warns that ‘many authorities contend that found poetry is a sub-poetry or a low form of poetry since its words are not original and its text is primarily expository prose’ (Gorrell 1989: 33). She evokes Lester again, and what he wrote in the Preface of his text Search for the new land: History as subjective experience (1969): ‘Although academicians, critics, poets, and others will be insulted, I call them poems’. The irony is not lost on me of the current movement in the qualitative research sphere within the academy to do exactly this nearly 50 years after Lester wrote – create poems with data, and call it poetry.

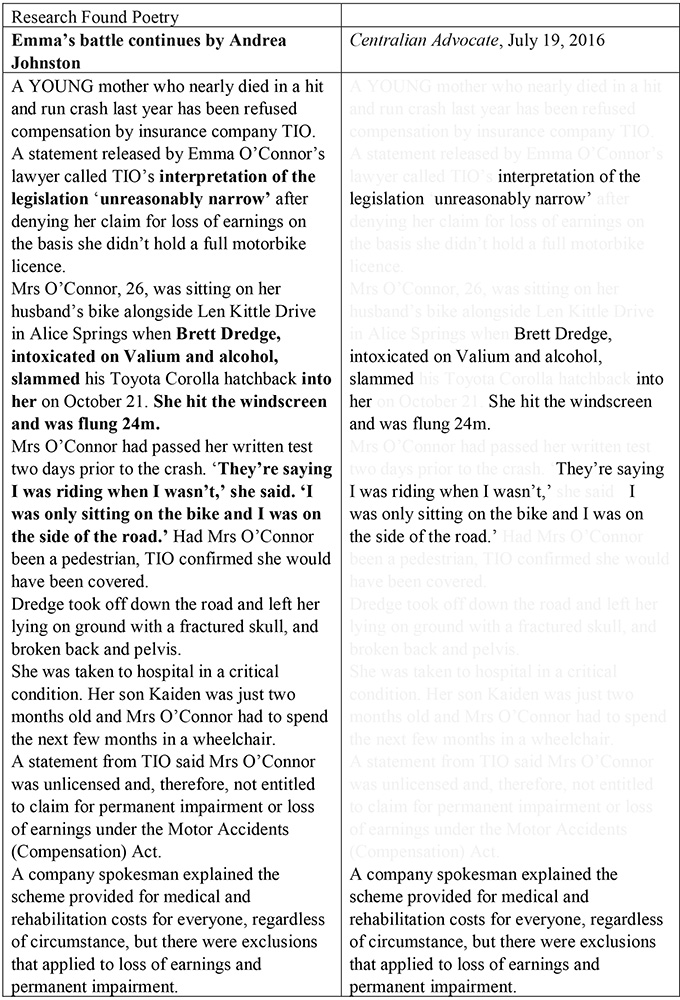

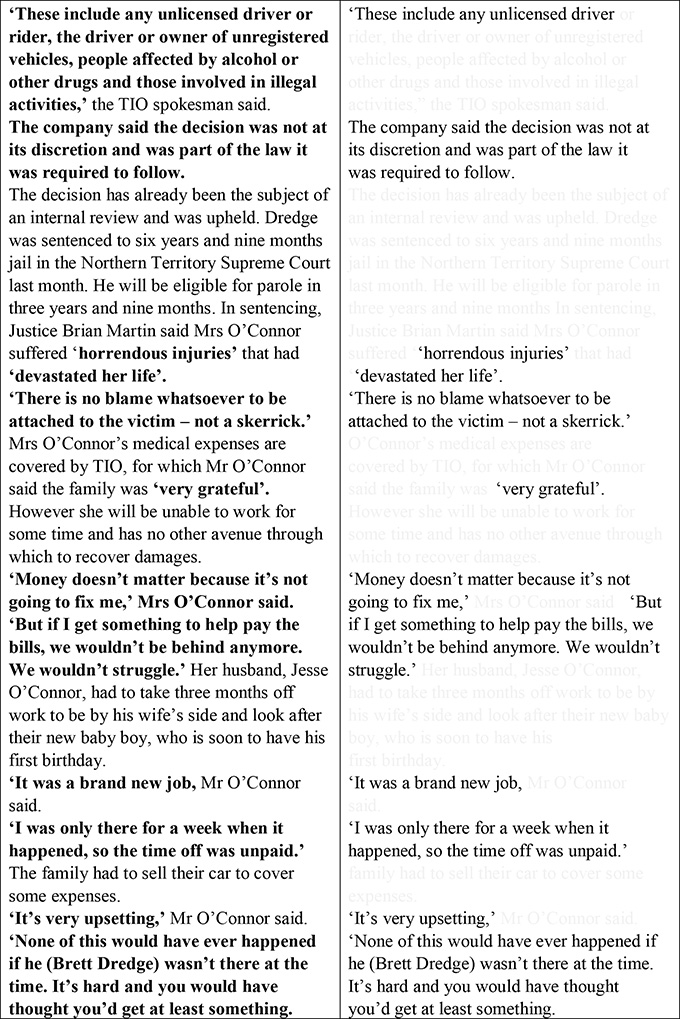

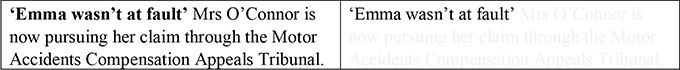

The poems found

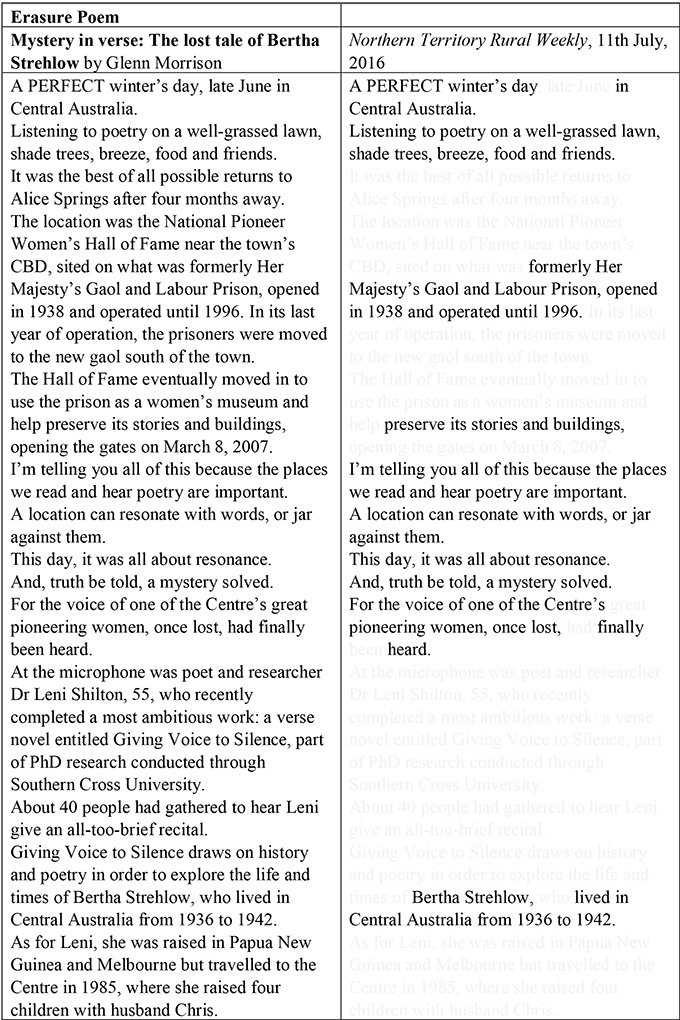

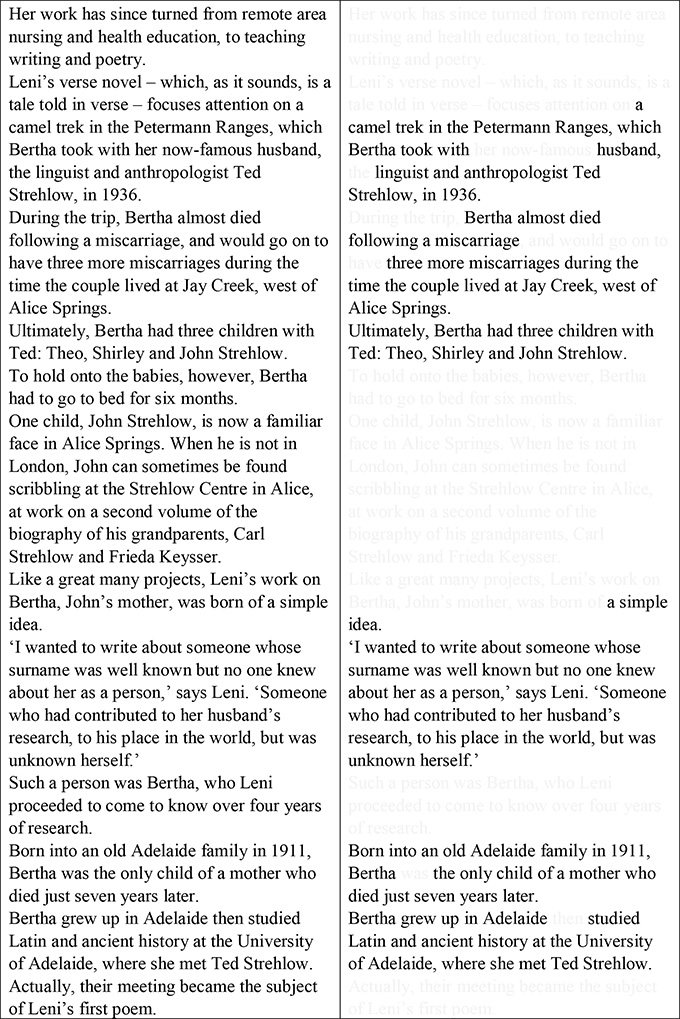

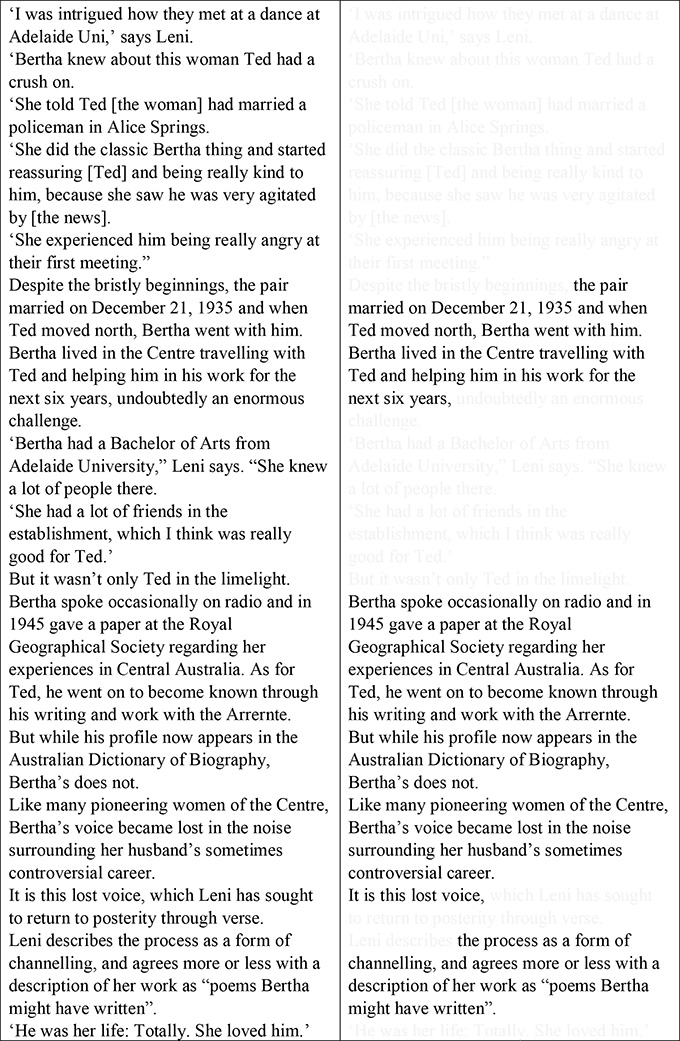

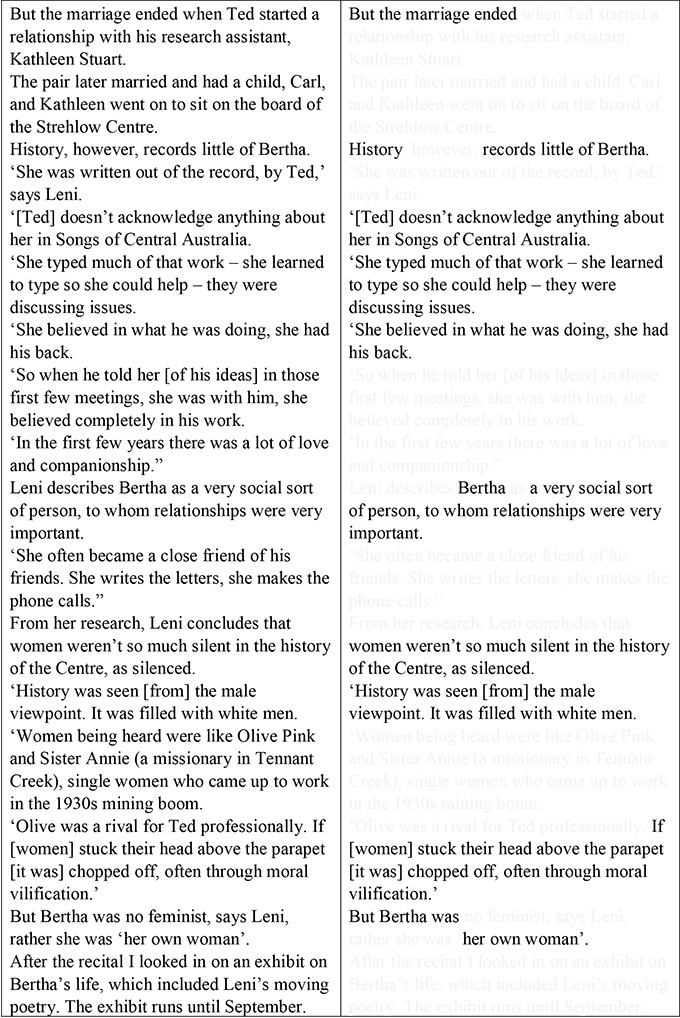

The poems I have created come from three different Northern Territory newspapers. The first is from the article ‘Mystery in verse: The lost tale of Bertha Strehlow’ by Glenn Morrison, published on 11 July 2016 in the Northern Territory Rural Weekly. The second poem is derived from the Tennant and District Times, published on 15 July 2016 and entitled ‘Local death in fatal crash’; there is no by-line on this story. And the third article, published in the Centralian Advocate on 19 July 2016 and entitled ‘Emma’s battle continues’, was written by Andrea Johnston. This last poem appropriates the notion of a Research Found Poem, by simply using quotes and some paraphrased narrative inquiry data cited in the article.

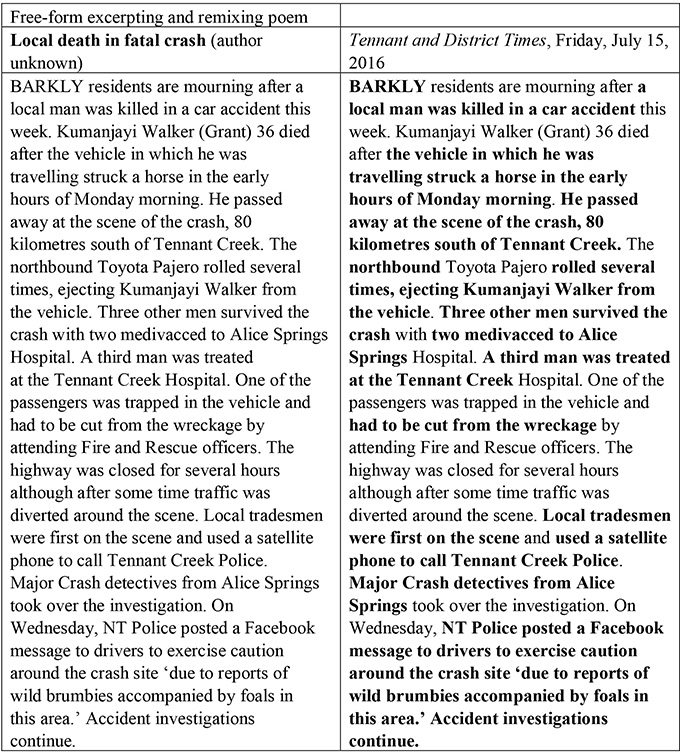

As mentioned above, all three articles were located on the first page, with overflow material within the newspaper. I have re-titled each poem – they do not carry the same title as in the original texts. I have tabulated the newspaper copy side by side with the copy I worked on, ‘sifting through material in order to find emphasis and meaning’ (Dangerfield Lewis 2012). My hope here is to aesthetically demonstrate the process of finding poetry within everyday newspaper writing, by using different shades of text, seemingly so the poetry will appear nestled within the text, while slowly detaching from it and emerging as a new or re-composed artefact; a demonstration, if you will, of poetry dwelling within ordinary language. I will then render the poems free standing after each table, for unfettered reading.

This lost voice

A perfect winter’s day in Central Australia

(listening to poetry on a well-grassed lawn, shade trees,

breeze)

formerly Her Majesty’s Gaol and Labour Prison,

(opened in 1938 until 1996)

Preserve its stories and buildings,

I’m telling you all of this because

the places we read and hear poetry are important.

A location can resonate with words, or jar against them.

This day, it was all about resonance.

And, truth be told,

a mystery solved.

For the voice of one of the Centre’s pioneering women,

once lost,

finally heard.

Bertha Strehlow,

lived in Central Australia from 1936 to 1942.

A camel trek in the Petermann Ranges,

which Bertha took with husband,

linguist and anthropologist Ted Strehlow, in 1936.

Bertha almost died following a miscarriage,

three more miscarriages during the time the couple lived at Jay Creek,

west of Alice Springs.

Ultimately, Bertha had three children:

Theo, Shirley and John Strehlow.

A simple idea,

says Leni (Shilton).

‘I wanted to write about someone whose surname was well known

but no one knew about her as a person.

Someone who had contributed to her husband’s research,

to his place in the world,

but was unknown herself.’

Born into an old Adelaide family in 1911,

Bertha was the only child of a mother who died just seven years later.

Grew up in Adelaide

studied Latin and ancient history

at the University of Adelaide,

where she met Ted Strehlow.

The pair married 1935

and when Ted moved north,

Bertha went with him

lived in the Centre

travelling with Ted

and helping him in his work for six years

Bertha spoke occasionally on radio

and in 1945 gave a paper

at the Royal Geographical Society

regarding her experiences in Central Australia.

As for Ted,

he went on to become known through his writing

and work with the Arrernte.

But while his profile now appears in the Australian Dictionary of

Biography,

Bertha’s does not.

Like many pioneering women of the Centre,

Bertha’s voice became lost in the noise

surrounding her husband’s sometimes controversial career.

It is this lost voice –

the process as a form of channelling her work –

as ‘poems Bertha might have written’.

The marriage ended

History records little of Bertha.

‘[Ted] doesn’t acknowledge anything about her

in Songs of Central Australia.

‘She typed much of that work –

she learned to type so she could help –

they were discussing issues.

‘She believed in what he was doing, she had his back.”

Bertha,

a very social sort of person,

to whom relationships were very important.

Women weren’t so much silent in the history of the Centre,

as silenced.

‘History was seen [from] the male viewpoint.

It was filled with white men.

If [women] stuck their head above the parapet [it was] chopped off,

often through moral vilification.’

But Bertha was ‘her own woman’.

Wild Brumbies

Reports of wild brumbies accompanied by foals

Northbound

80 kilometres south of Tennant Creek.

A local Barkly man killed in a car accident

(he passed away at the scene of the crash)

the vehicle struck a horse in the early hours of

Monday morning,

rolled several times,

ejecting Kumanjayi Walker (Grant)

36.

Local tradesmen were first on the scene

(used a satellite phone to call Tennant Creek Police)

Three other men survived the crash

(one had to be cut from the wreckage):

two medivacced to Alice Springs;

a third man treated at Tennant Creek.

Police Facebook message to drivers:

Exercise caution

due to reports of wild brumbies accompanied by foals in this area

Alice Springs Major Crash detectives

continue accident investigations.

Unlicensed

There is no blame whatsoever to be attached to the victim

– not a skerrick.

Emma wasn’t at fault.

They’re saying I was riding when I wasn’t,

I was only sitting on the bike and I was on the side of the road.

Brett Dredge,

intoxicated on Valium and alcohol,

slammed into her.

Unlicensed

and not entitled to claim for permanent impairment or loss of earnings.

Medical and rehabilitation costs for everyone,

but exclusions applied to loss of earnings and permanent impairment:

any unlicensed driver or rider…

Unlicensed.

The company said decision not at its discretion

and part of the law required to follow.

Unreasonably narrow

interpretation of the legislation.

Horrendous injuries devastated her life:

she hit the windscreen

and was flung 24m.

Money doesn’t matter because it’s not going to fix me.

But if I get something to help pay the bills,

we wouldn’t be behind anymore.

We wouldn’t struggle.

It’s very upsetting,

It was a brand new job,

I was only there for a week when it happened,

so the time off was unpaid.

None of this would have ever happened

if he (Brett Dredge) wasn’t there at the time.

It’s hard.

Conclusion

Constrained by words already written by other writers, it is with trepidation that I set out to reconstruct their words poetically. Painstakingly, the poems filtered through the prose and emerged on my page, percolating into a form slowly becoming more and more lyrical. As mentioned above, Dillard writes this practice is ‘… editing at its extreme; writing without composing’ (Dillard 1995: x). But now, I am no longer sure about her final claim ‘writing without composing’. By selecting and editing, by choosing pauses through lineation and punctuation, I feel my practice has been about both editing and composing – or perhaps re-composing. Are these poetic offerings ‘sub-poetry or a low form of poetry’ as Gorrell queries (1989: 33)? I do not know but I do know that by synthesising the narrative of each piece with lyrical meter through elimination of surrounding words, the poems emerge from the prose and perform as I hoped – I believe the story of the original text is still evident, perhaps more dramatically or evocatively, than in its original form, in each poem.

Burdick, M 2011 ‘Researcher and teacher-participant found poetry: Collaboration in poetic transcription’, International Journal of Education & the Arts, 12 (SI 1.10).

Butler-Kisber, L 2002 ‘Artful portrayals in qualitative inquiry: The road to found poetry and beyond’, Alberta Journal of Educational Research, XLVIII (3), 229–239.

Dangerfield Lewis, J 2012 ‘Finders Keepers: Using found poetry to promote academic literacy and deeper understanding across the curriculum: a multi-grade curriculum’, Master of Arts (Education) thesis, California State University, Sacramento

Dillard, A 1995 Mornings like this, Found Poems, New York: Harper Collins Publishers

Dow, W 2016 ‘Profiles of lived experience: Charles Reznikoff, Muriel Rukeyser and Mark Novak’ in S Joseph & R L Keeble (eds) Profile pieces, journalism and the ‘human interest bias’, New York: Routledge, 116–137

Dunning, S and Stafford, W 1992, Getting the knack, Illinois: National Council of Teachers of English

Frazier, C H 2003 ‘Building community through poetry: A role for imagination in the classroom’, English Journal, May 2003, 92: 5, 65-70

Gilroy, H 1967 ‘A game modern bards play: Finding poetry; alert eyes cull unintentional verses from any prose’, The New York Times, August 17, at http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F50E1EFC345E137A93C5A81783D85F438685F9 (accessed 27 July 2018)

Gorrell, N 1989 ‘Let Found Poetry help your students find poetry’, English Journal, February 78: 2, 30-34

Joseph, S 2017 ‘Found Poetry as literary cartography: Mapping Australia with prose poems’, TEXT Journal of Writing and Writing Courses, Beyond the line: contemporary prose poetry, Special Issue no 46, 1-17

Kleon, A 2010 Newspaper blackout, New York: Harper Perennial

Lahman, M & Richard, V 2014 ‘Appropriated poetry: Archival poetry in research’, Qualitative Inquiry, vol 20 (3), 344–355

Lester, Julius 1969 Search for the new land: History as subjective experience, USA: Dial Press

Patrick, L 2016 ‘Found Poetry: Creating space for imaginative arts-based literacy Research’, Writing Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, vol 65, 384-403

Patrick, L 2013 ‘Found Poetry: A tool for supporting novice poets and fostering transactional relationships between prospective teachers and Young Adult literature’, PhD thesis, Ohio State University; Published by ProQuest LLC (2015)

Poets.org 2018 Erasure: Poetic Form, 10 May, at https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/text/erasure-poetic-form (accessed 30 July 2018)

Prendergast, M 2006 ‘Found poetry as literature review: Research poems on audience and performance’, Qualitative Inquiry, 12 (2), 369-388

Prendergast, M 2009 ‘Introduction: The phenomena of poetry in research’, in M Prendergast, C Leggo and P Sameshima (eds), Poetic inquiry: Vibrant voices in the social sciences, Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers, xix-xlii

Prendergast, M 2015 ‘Poetic inquiry, 2007–2012: A surrender and catch found poem’, Qualitative Inquiry Vol. 21 (8), 678–685

Robson, M and Stockwell, P 2005 Language in theory: A resource book for students: ABCD, Oxon, UK: Routledge

Thought.co 2018, Introduction to Found Poetry, April 6, at https://www.thoughtco.com/found-poetry-4157546 (accessed 30 July 2018)

Wiggins, J 2011, ‘Feeling it is how I understand it: Found Poetry as analysis’, International Journal of Education & the Arts, Special Issue: Lived Aesthetic, Volume 12, 1-19